In a 1967 article entitled “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White,” James Baldwin cautioned against loosely comparing trauma: “One does not wish to be told by an American Jew that his suffering is as great as the American Negro’s suffering. It isn’t, and one knows that it isn’t from the very tone in which he assures you that it is.”

Despite Baldwin’s caution, the desire to compare Black and Jewish experiences has resulted in a litany of dramatic explorations. Peaking in the late 1980s and early ’90s, when so-called “Black-Jewish relations” became strained, these works have had uneven legacies. Some—like Alfred Uhry’s Driving Miss Daisy—were outright offensive in their tokenism and stereotype; others—like Anna Deavere Smith’s Fires in the Mirror—have endured for their innovative exploration of dramatic form.

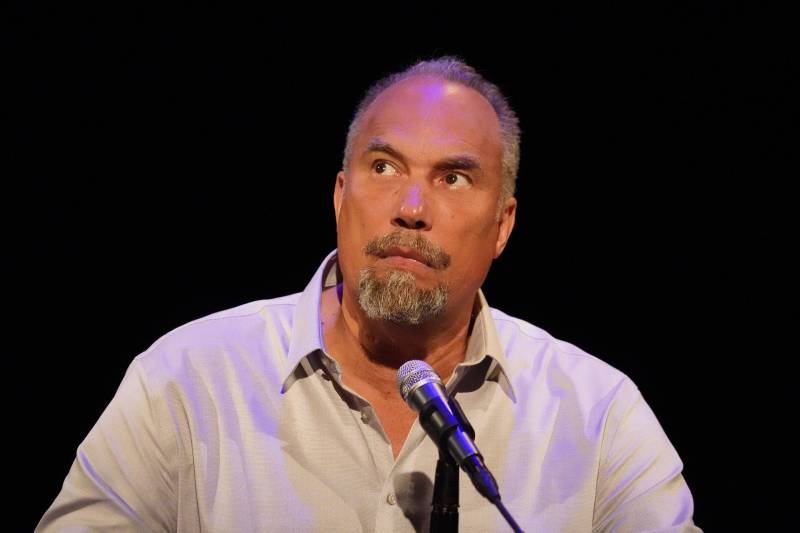

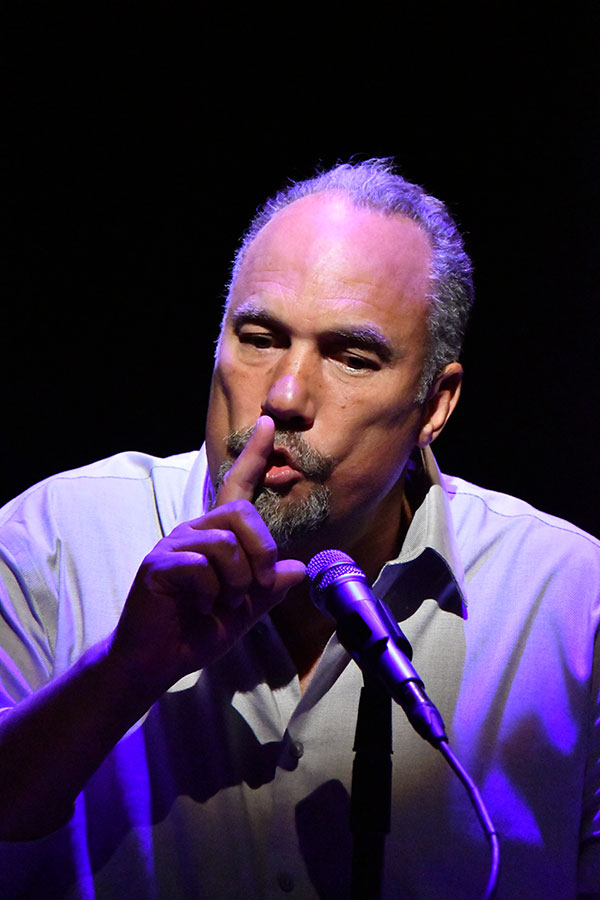

The latest iteration of this comparative impulse is Roger Guenveur Smith’s one-man show, Otto Frank, playing at the Magic Theater in San Francisco through March 29. Smith, well-known from his roles in Spike Lee’s films, is also one of our era’s great solo performers. Having previously embodied Frederick Douglass, Huey P. Newton, and Rodney King, Smith teams up here with longtime collaborator Marc Anthony Thompson—better known as Chocolate Genius Inc.—to produce an hour of intimate, yet emotionally monotone, theater.

Like Smith’s other plays, Otto Frank is both history lesson and eulogy. Smith portrays Otto, sole survivor of the Frank family and publisher of his daughter’s famed diary, as haunted by guilt and sorrow. The staging in this thrust theater is beautifully minimalist, populated only by a single desk, chair, and microphone. We are both, it seems, inside the Franks’ “secret annexe,” at the table that Anne fought to claim as writing space in her July 13, 1943 entry, but also in some kind of Beckettian bardo state. Frank speaks to his daughter from beyond the grave, narrating the circumstances of his life, bearing witness to her death, and lamenting the state of the world since his own passing in 1980.

Smith’s portrayal brims with intensity. He sits with monk-like meditativeness for an hour, arms outstretched and eyes wide open. I can count on one finger the number of times I noticed him blink. The resonant overtones of Thompson’s glassy accompaniment shake the walls and interrupt the oration. In these musical interludes, Smith pauses the history lesson and breaks out into puppet-like gestures, melodious song, and one final, chilling scream.