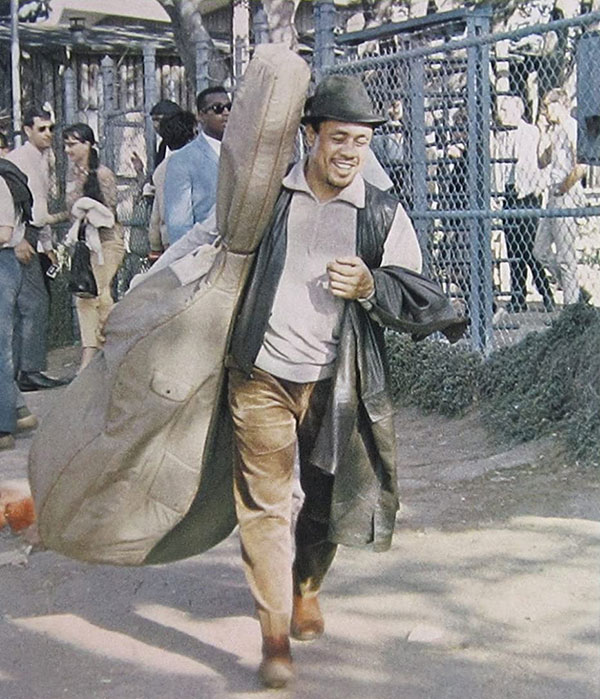

In the summer of 1939, a 17-year-old bassist named Charles Mingus made a fateful trip to the Bay Area.

While already possessed by extraordinary ambition—a racially ambiguous jazz artist drawn to Stravinsky and Ellington, the blues, and church call-and-response worship—the protean bassist had felt misaligned for every path that presented itself. That included his 1939 gigs which brought him to Oakland and San Francisco with the Floyd Ray Orchestra, a now-forgotten Los Angeles-based dance band.

An encounter with North Beach artist Farwell Taylor, however, changed the course of Mingus’s life, and initiated a decades-long connection to the Bay Area. Their fast friendship introduced the teenager to a world of poets and painters, philosophers and novelists. Providing the young bassist and composer with refuge whenever money was thin and moral support when depression closed in, Taylor opened up an infinite vista into which the bassist gradually expanded. And expanded. And expanded.

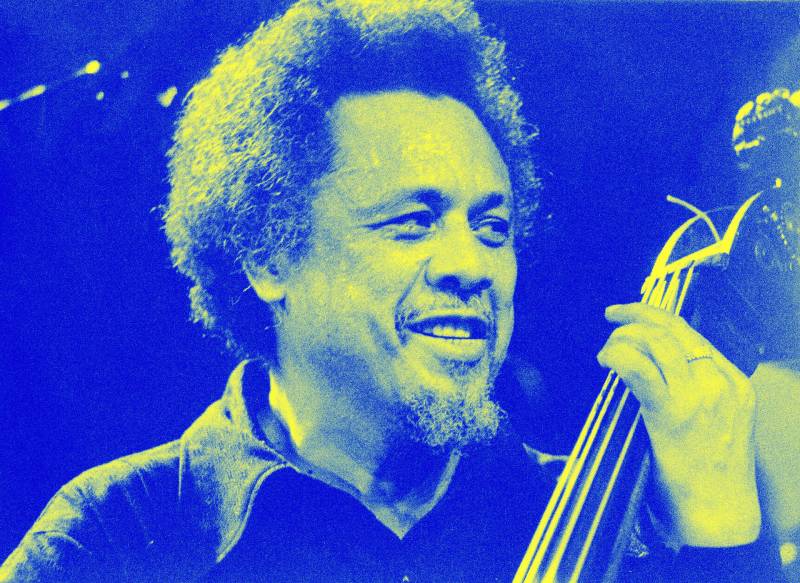

On April 22, 2022, Charles Mingus would have been 100 years old. A singular composer, volatile bandleader, outspoken activist and virtuosic improviser, Mingus created a body of music as profound, diverse and emotionally unbridled as any in American music. And his centennial coincides with a moment in American history, and in the Bay Area especially, uncannily primed for his prescient music and its social and political overtones.

‘Mingus Dealt With All the Muses’

Within jazz, Mingus intersected on stage and in the studio with artists spanning the entire 20th century, from Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker to Randy Brecker and John Scofield. Beyond jazz, his breadth remains just as imposing. Collaborating with leading figures across numerous disciplines, including Langston Hughes and Alvin Ailey, Joni Mitchell and Dimitri Tiomkin, Jean Shepherd and John Cassavetes, “Mingus dealt with all the muses,” alto saxophonist Charles McPherson says today.

McPherson played and recorded intermittently with Mingus from 1960-72, and decades later, he continues to sound awed when discussing the scope of the composer’s creative realm.

“He wrote pieces protesting social injustice,” McPherson says. “He wrote love songs dealing with eros, romantic love, and sometimes he wrote love songs with reverence dealing with agape, love of God. He wrote from different angles. Sometimes it was dance, like ‘Ysabel’s Table Dance,’ or blues and folk music and bebop. He loved Charlie Parker. He was very knowledgable about Western classical music: Stravinsky, Hindemith, Prokofiev. More than anything, he revered Duke Ellington. You stir all that up, that’s how you get a Charles Mingus.”

A Distinct Bay Area Ingredient

Mingus absorbed plenty from his Los Angeles upbringing, including several disillusioned years delivering mail, or ghostwriting Hollywood film scores for Dimitri Tiomkin. But he seemed most in tune in San Francisco’s bohemian circles.

Even after he moved to New York City in 1951, the Bay Area served as Mingus’ second home. He returned repeatedly to settle into its clubs for extended residencies, and to commune with Farwell Taylor. It’s no coincidence that some of his signature artistic triumphs took place here. (Certain Bay Area markers found their way into his recordings, also: cable car bells and foghorns in his version of “A Foggy Day,” or an ode to Taylor titled “Far Wells, Mill Valley.”)

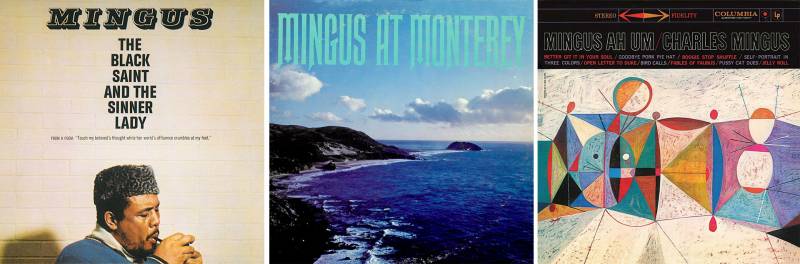

Rather than presenting polished compositions, Mingus treated performance as an in-progress process, often billing his confederation of musicians the “Mingus Jazz Workshop.” It was a moniker picked up by the North Beach nightclub that became one of his primary San Francisco outlets, where he recorded the thrilling 1964 album Right Now: Live at the Jazz Workshop for Berkeley label Fantasy Records. Just a few months later, he made an epochal appearance at the Monterey Jazz Festival with a big band, premiering his roiling, political opus “Meditations on Integration” (as well as an extended medley of Ellingtonia), released on Mingus at Monterey.

Social and Political Overtones Ahead of Their Time

In 2022, the scope of Mingus’ legacy is enduring and, indeed, increasing. He was a pioneering entrepreneur who was among the first jazz musicians to launch his own label, Debut Records, independently releasing a catalog eventually acquired by Fantasy in Berkeley. His DIY efforts rippled across the music business, connecting to future Bay Area independent labels like 415 Records, Alternative Tentacles and Hieroglyphics Imperium.

In much the same way, Mingus’s experimental bent as an artist often intersected with his radical opposition to white supremacy and prejudice. The felicitous marriage of activism and aesthetics has also resonated deeply in the Bay Area, across the decades.

“He started using mixed media and prerecorded sounds in his recordings, all this stuff you start to see incredible young composers like Samora Pinderhughes and Ambrose Akinmusire doing today,” notes San Francisco bassist Marcus Shelby.