When an artist has been creating work in various forms for six decades, that work becomes known to different audiences in different ways. For 91-year-old Faith Ringgold, the breadth and volume of her artistic career has spawned any number of isolated fan clubs. Many will be most familiar with her “story quilts,” which she began making in 1983 and which have toured extensively over the years. Meanwhile, children of the ’90s grew up reading Ringgold’s illustrated book Tar Beach, about her own childhood in Harlem. Others may know only of her activism, much of it directed at New York institutions for failing to show Black women artists or hire Black curators.

Hence, the incredible gift of Faith Ringgold: American People at the de Young, which allows all those audiences to see a life’s work beyond the limitations of a specific art history lecture or a passing glimpse at a narrowly focused museum show.

The retrospective, curated by the New Museum, opens with a 1963 painting inspired by a racist encounter from the artist’s childhood. The show ends with a series reflecting on her 1992 move from Harlem to a predominantly white suburb of New Jersey. While these bookends capture Ringgold’s desire to depict—not sugarcoat—the realities of life for Black women in America, her work does not exist solely within this context. The great pleasure in viewing so much of Ringgold’s art is learning that she cannot be assigned to any one category, be it Black artist, textile artist, feminist, activist, conceptual artist or storyteller.

As a Black woman, Ringgold was routinely rejected, condescended to and relegated to ancillary roles by a predominantly white and male New York art world as she began her career in the 1960s. Still, she took up space: in sidewalk protests, with costumed performances, and, in her first solo show, in her large-scale paintings. Ringgold’s American People Series was first shown in a 1967 exhibition at New York’s Spectrum Gallery, and culminated in three “murals” (as she called them), two of which are on view at the de Young. (In a story that repeats itself across so many women’s artistic careers, these murals rarely emerged from Ringgold’s storage for decades after.)

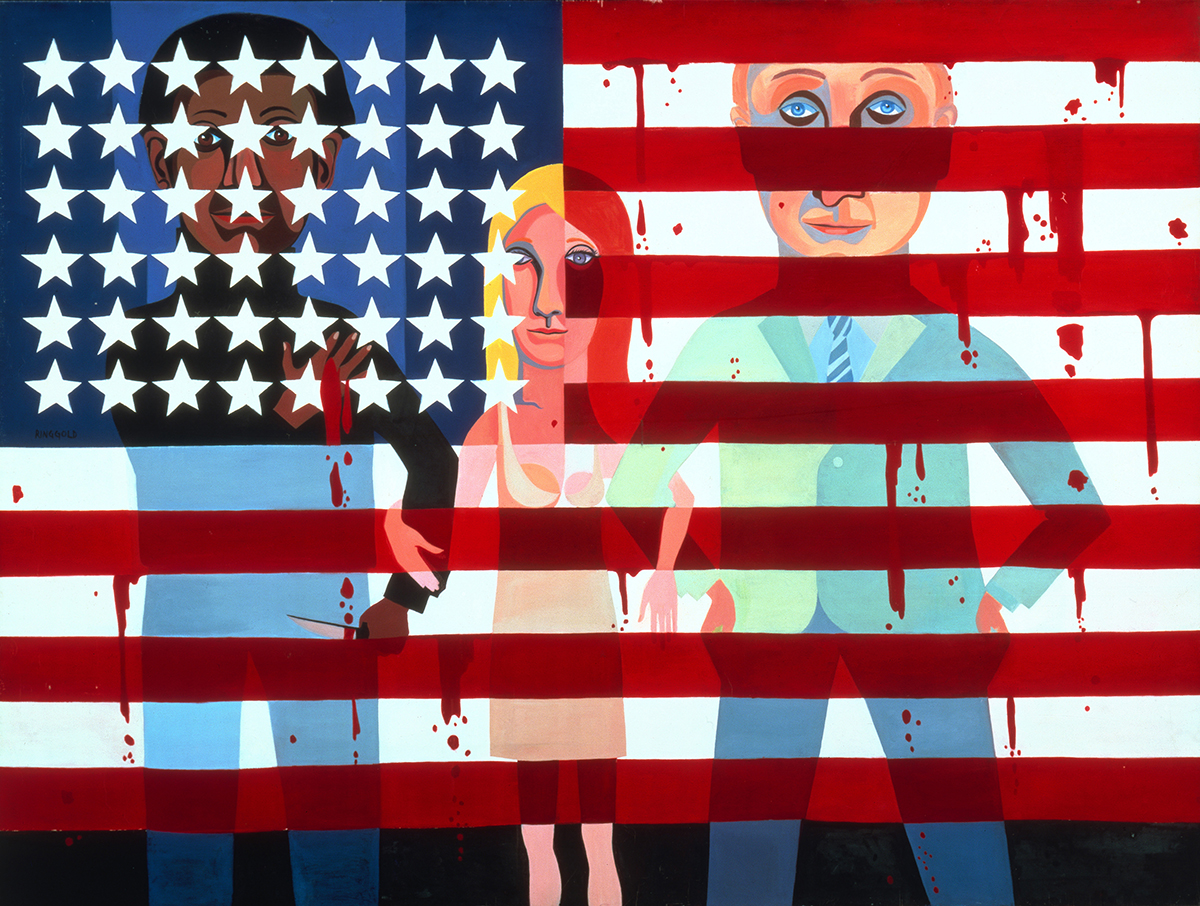

In one, American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding, three figures stand arm-in-arm, intermingled with the stars and stripes: a Black man, a white woman and white man. Noticeably missing is Ringgold’s own identity. Black women were simply not part of the conversation at the time, she later explained.