While the San Francisco Bay area was focused on the larger Outside Lands festival, where mainstream punk band Green Day took the main stage earlier this month, 3 miles south, in the city’s South of Market neighborhood, a smaller minority of predominantly POC and queer folks gathered at Bindlestiff Studios to enjoy the seventh annual Aklasan Fest. The punk scene as we know it is usually a space dominated by cis white men, but in true punk fashion, Aklasan Fest prioritized the often unheard and unseen voices of punk, creating an inclusive space that was not only educating attendees about Filpino oppression but also highlighting the struggles of marginalized identities through the lens of Filipinos and Filipino Americans.

Rupert Estanisalo, who founded the event in 2014, says Aklasan Fest is “the only Filipino punk festival or event like this.” He says he wanted to “create a space just for Filipino punks that looked like me and cared about the issues I cared about that are anti-imperialist, activist and pro-people of color.” In Tagalog, Aklasan means “Rise Up,” and after a two-year pandemic-induced hiatus, it returned, featuring 15 bands from across the country.

As a Filipino-American photographer, Aklasan is important because it creates a space for us to gather, as a community, to express ourselves and tell our stories artistically. Being the only Filipino punk show in the nation in itself is special. The festival is carving its path and place in the punk scene, surrounded by a robust and tight-knit community who cares about the music and the people.

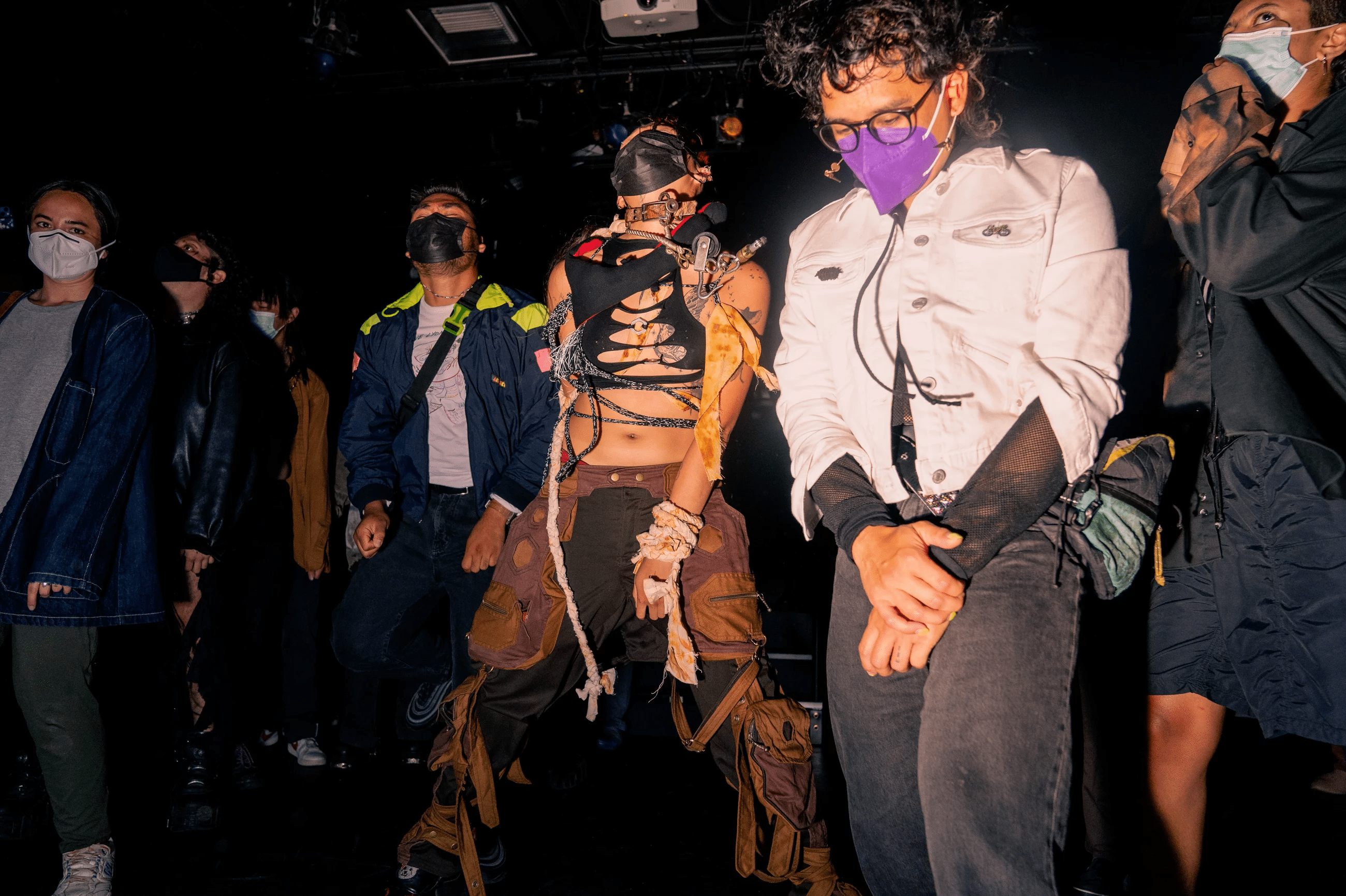

In the dark setting of Bindlestiff, you find yourself surrounded by straight-edge, immigrant, tatted, vegan, working class, Filipino and Filipino-American hardcore punks as well as fans who range in ages, races and genders, moshing to music in both Tagalog and English. Romeo Reyes-Pagdilao, the lead singer of Silakbo, says, “You got bands like us (Silakbo) or our friends like Material Support and Moxiebeat. They got songs talking about our experiences, being Filipino, working people, and growing up in the bell of the beast, the United States.”

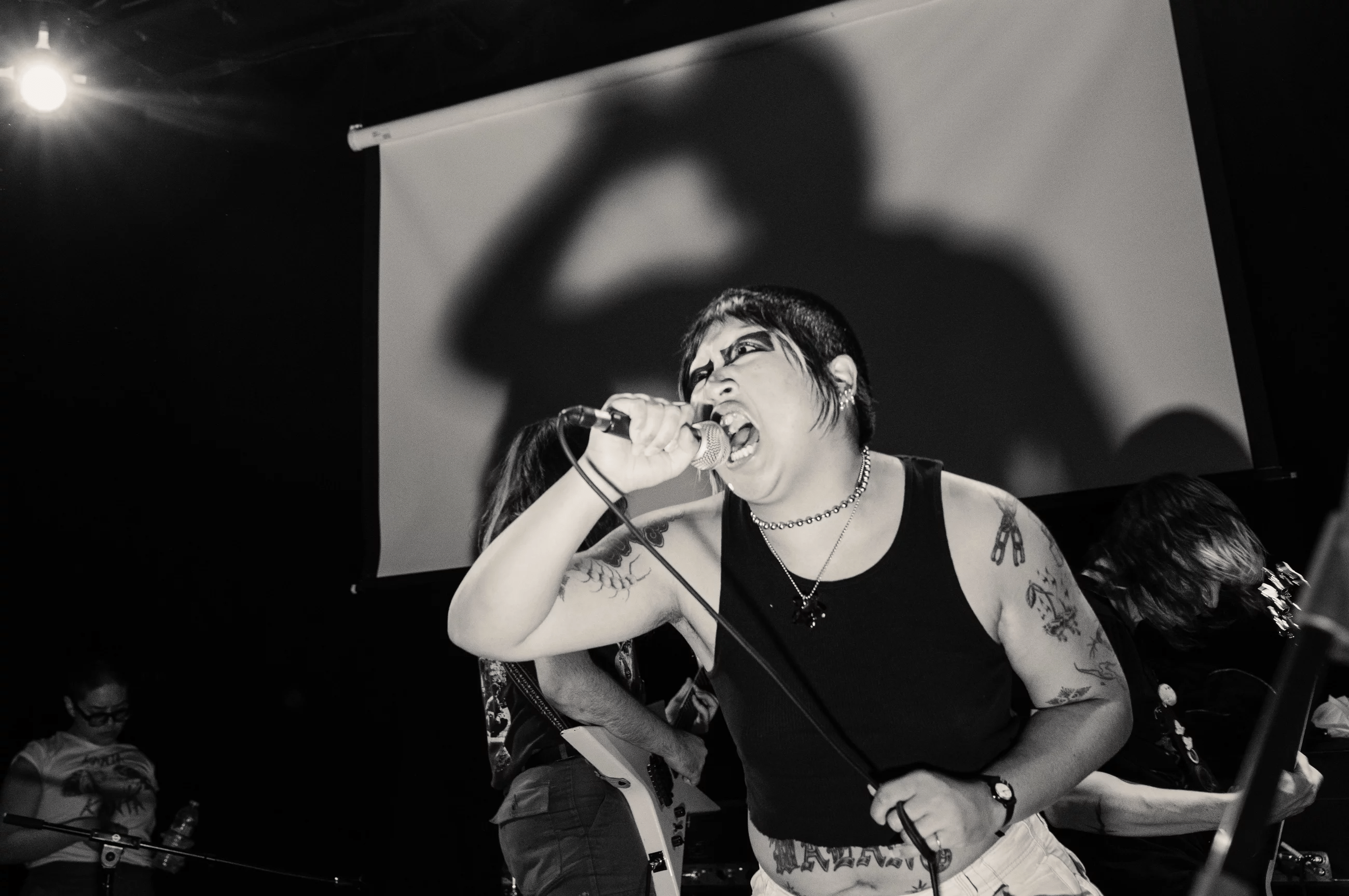

Material Support performed “Cost of Living,” written to highlight how difficult it is for working-class people to afford basic housing or food for their families in America. One of the most memorable moments of the festival was when Jackie Mariano, Material Support’s lead singer, gutturally sang out “racialized mass graves” to punctuate the end of the song. “When we wrote it,” Mariano says, “I was thinking of the concept of how we’re forced to navigate the world by class and race. My dad, who died in 2016, is buried in a nice Catholic cemetery in Queens (NY) in a conservative, white, middle-class neighborhood, and with that being our only ‘real estate,’ I still felt like we were out of place, didn’t belong there. What a different juxtaposition for my Filipino immigrant dad to be laid to rest in a nice place, versus many other people who die in war, occupation and are dumped in mass graves. When COVID happened, it’s like the concept of racialized mass graves was made real on Potter’s Field — people constantly forgotten because they were marginalized in life and in death.”