In 2014, the League of American Orchestras, a service organization representing professional and amateur symphony orchestras around the United States, published a study on diversity and found that only 1.4% of orchestra musicians were Black.

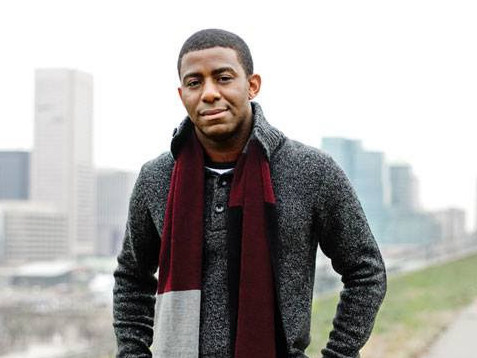

In 2022, it’s hard to say if that figure has gotten better or worse, said Jennifer Arnold, a co-founder of the Black Orchestral Network. Arnold spent 15 seasons playing viola with the Oregon Symphony and now is director of artistic planning and operations for the Richmond Symphony.

“There’s a real need to actually be transparent about what’s happening in the industry, in terms of Black people,” Arnold said. “We do not know how many Black people are in orchestras. And I say that as a representative of Black Orchestral Network. One of our calls is, let’s start collecting data. Let’s find out, have we done better than the 1.4% number that is going out there? That 1.4% is kind of based on well, “I see a Black person on that stage in that orchestra.” That’s not data.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))