Editor’s note: This story is part of That’s My Word, KQED’s year-long exploration of Bay Area hip-hop history, with new content dropping all throughout 2023.

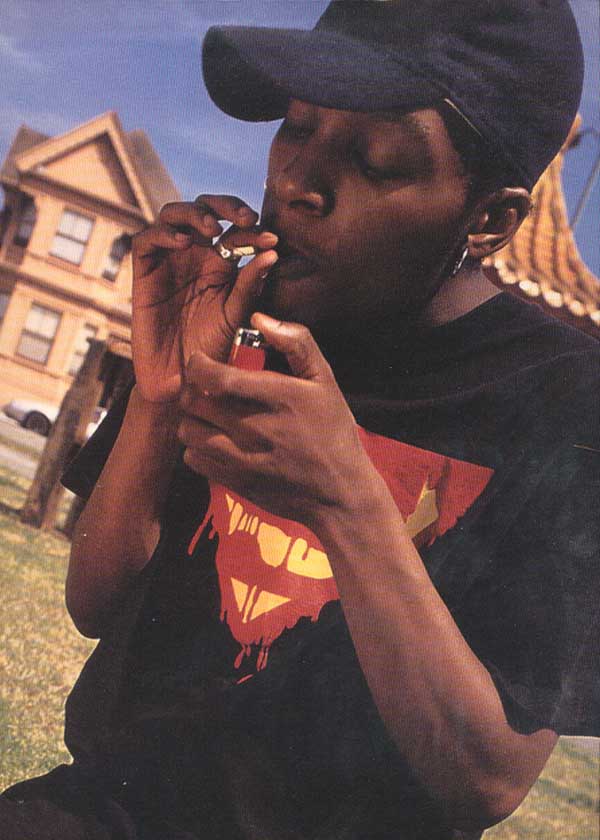

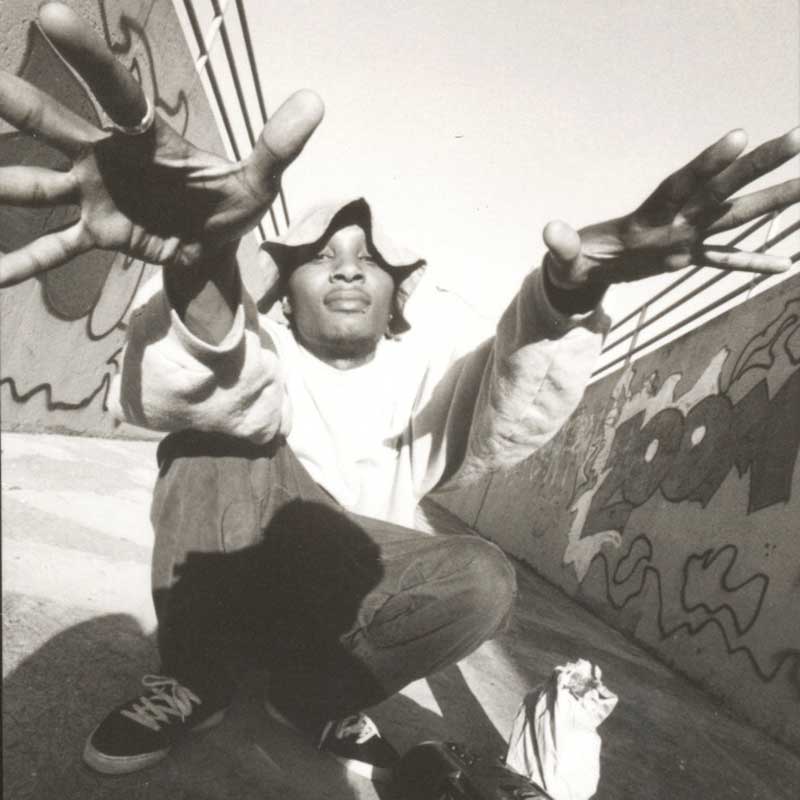

Del the Funky Homosapien’s sophomore album No Need For Alarm is a Bay Area classic that proved his uncompromising skill and helped establish the Hieroglyphics collective nationally as a creative force. Here, from an interview condensed for length and clarity, Del, a.k.a. Teren Delvon Jones, recalls the circumstances of the album’s recording, artwork and reception.

As told to: Gabe Meline

When I was making No Need for Alarm, I was in a dark space. I had a lot of issues growing up. I don’t think I was aware of it then, but looking back, I was in an angsty space. I was dealing with issues of abuse, being different from everybody, pretty much being a loner except for people that was into the culture I was, which was not that many. I appreciated the camaraderie that I had, too, don’t get me wrong. But yeah, I had an attitude.

I had come out with my first album, I Wish My Brother George Was Here, which I made with Ice Cube — he’s my cousin. And the response from a lot of heads was not at all what I expected. It wasn’t celebratory. It was more like, “OK, you’re selling out. Why’re you rappin’ over P-Funk shit?” So, that caused me to be, like, “All right, I’m just going all in this time, just to show motherfuckers what I really be on.”

And I think that hurt Cube — I think he was like, “OK, well, damn, you didn’t like the first album?” I’m like, “Nah, nah, I like it, but, you know…” It was just that, from my little social network, I wasn’t getting the love that I thought I was going to get. It was the opposite. Because motherfuckers already done heard all my demos and shit. They knew how wild I could get.

So that’s what I did for No Need for Alarm. I’m a battle rapper by nature. That’s what I really do. It was limited on the first album. And that was probably a wise decision, because a lot of people can’t understand that shit.

I was in transition. I was couch-surfing for a minute, living with different people, roommating. In ’93, I ended up living in New York mixing the album, doing whatever I needed to do for the album, so I had a little flat in New York that I was staying out of.