A low-key high-wire act of emotional delicacy and devastating power, All of Us Strangers is a perfect holiday movie. For adults in a certain mood, that is, for whom Christmas (or the winter solstice) opens a bittersweet portal for remembering and revisiting deceased relatives, friends and lovers.

All of Us Strangers (opening Dec. 25 in the Bay Area) also speaks eloquently to anyone feeling alone or alienated at this particular juncture and who hankers, even tentatively, for the company of a kindred spirit. It’s one of my favorite films of the year, so let me be even more inviting: This is a splendid movie for people who love concise storytelling and precise filmmaking steeped start to finish in mystery and ambiguity.

Adapted from the 1987 novel Strangers written by the Japanese television dramatist and author Taichi Yamada (who died in late November at 89) and transposed by writer-director Andrew Haigh to a familiar yet slightly off England, All of Us Strangers centers on a single gay man in his 40s who has chosen — or gradually, infinitesimally defaulted to — a life of isolation.

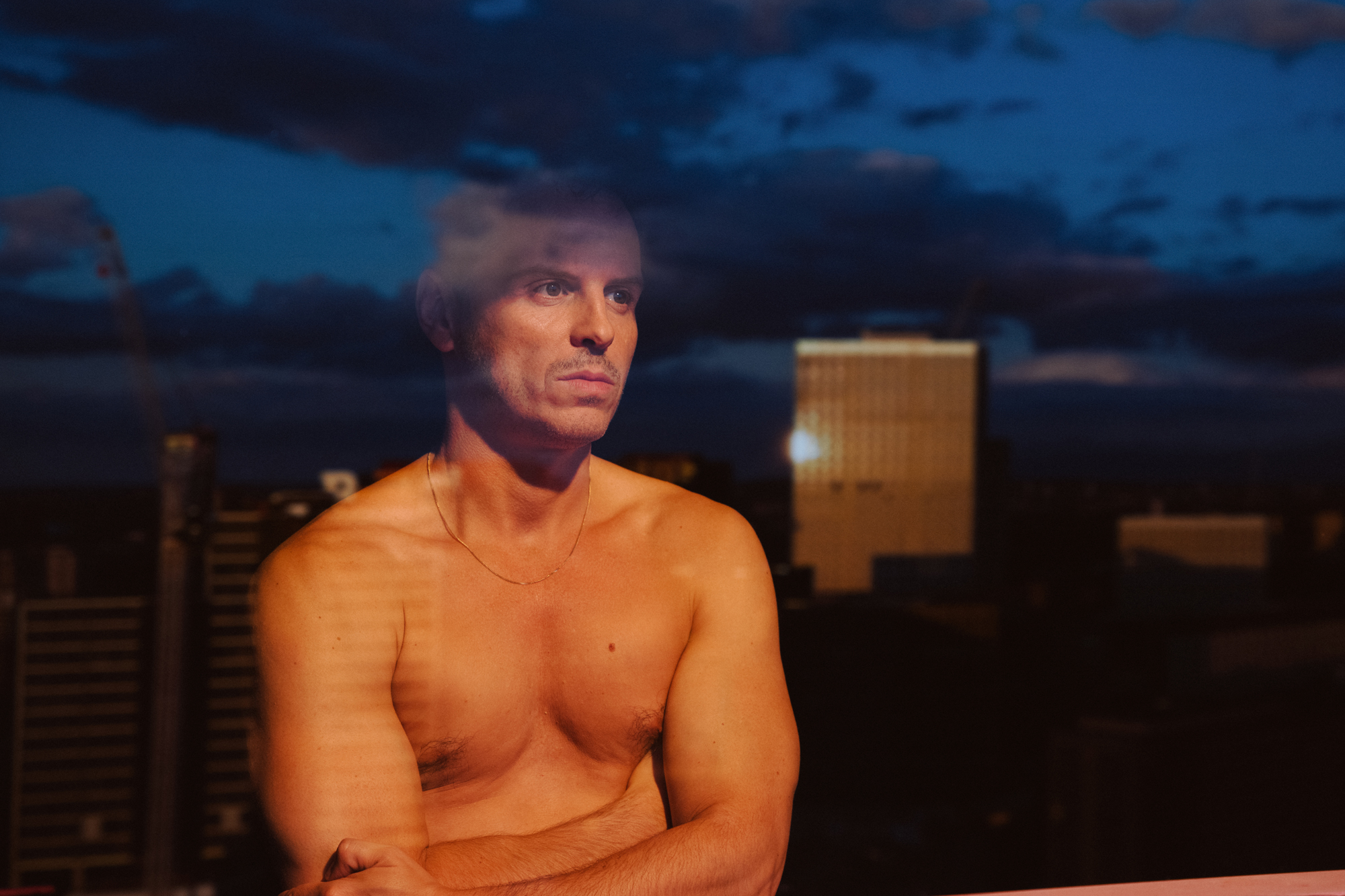

We could call it a life of the mind (without the hothouse Hollywood hysteria of Barton Fink), for Adam (Andrew Scott) is a screenwriter, an erstwhile inventor of worlds. All of Us Strangers begins in his apartment in a new, weirdly uninhabited high-rise on the outskirts of a strangely twilit London. Did the apocalypse happen this week? That would explain why there’s nothing in his fridge except leftover takeout.