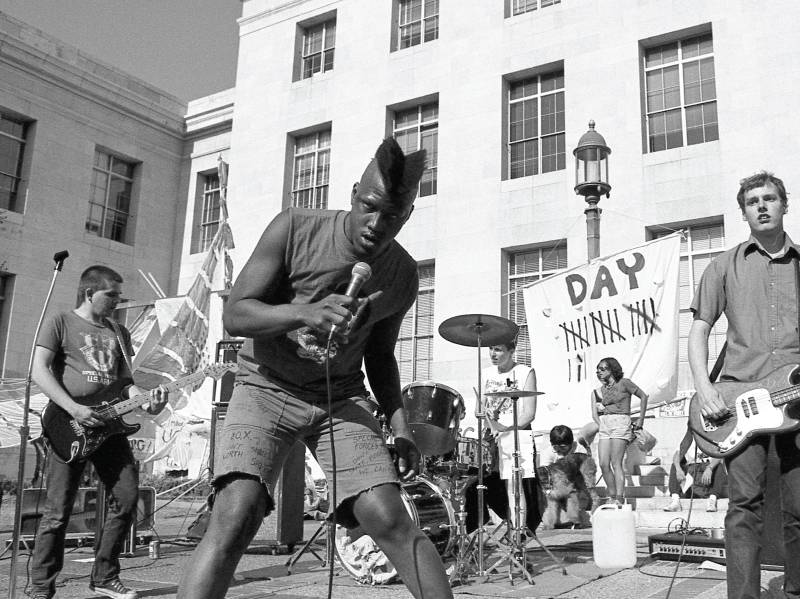

Stand at the back of a punk club like Berkeley’s 924 Gilman nowadays, and the entire crowd will invariably be lit up with a hundred little screens, all recording a moment in time to share online later. But at the primordial 924 Gilman of yesteryear, there was often just a single camera in the crowd, held in Murray Bowles’ hand flicking out far above his head, followed by a quick flash.

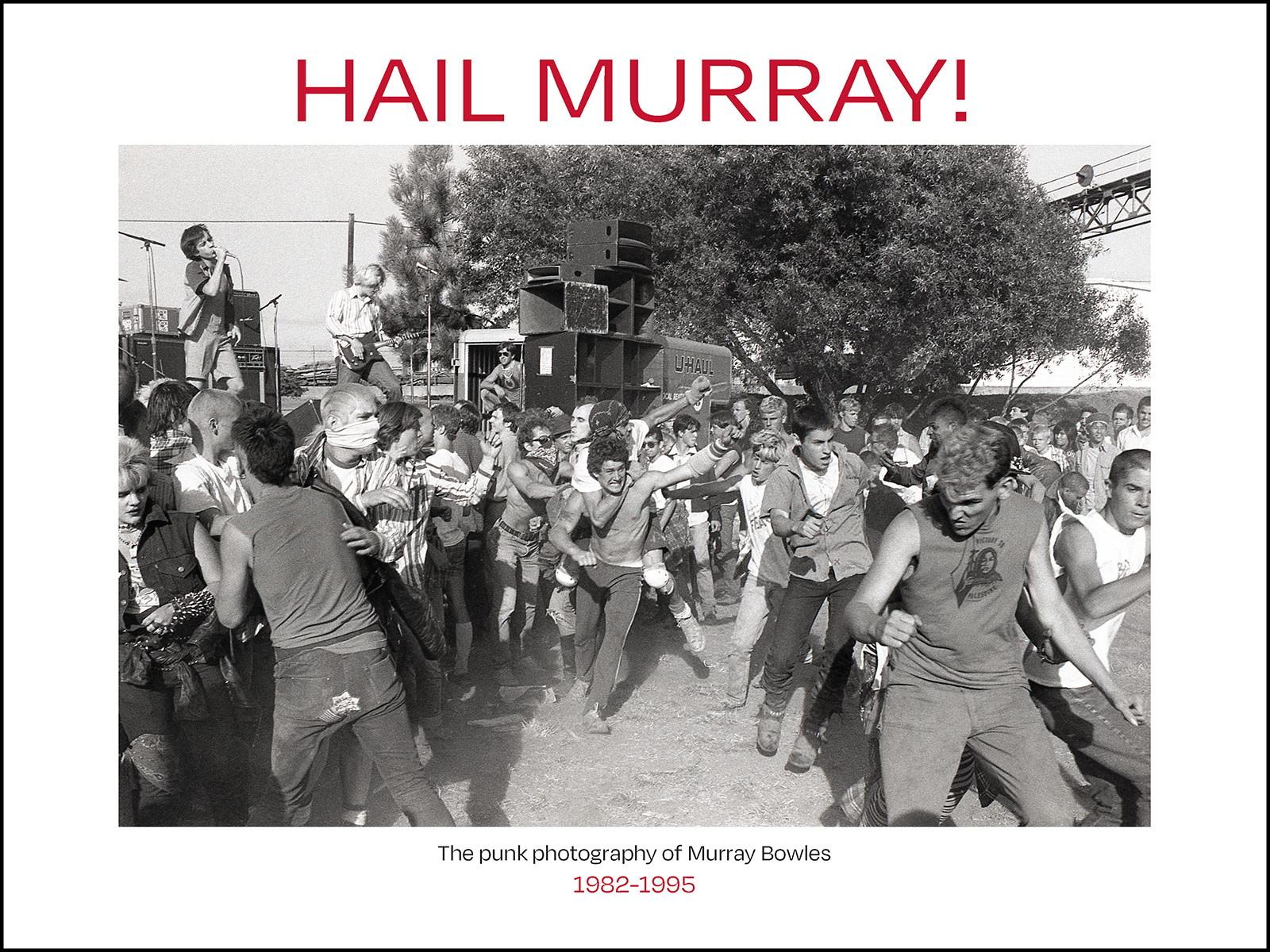

Hail Murray!: The Bay Area Punk Photography of Murray Bowles, 1982–1995 (Last Gasp; $39.95) is a sprawling, 270-page monograph of black and white photos representing a wildly creative and supercharged era of local underground music. If you attended any Bay Area punk shows from the 1980s through the 1990s, you likely crossed paths with Murray, its de facto chronicler. Wrapped in a decidedly civilian package — an older man with floppy brown hair, bearded, and bespectacled — he looked more like a computer programmer than a punk (and, unbeknownst to many, he actually was a programmer of note in early Silicon Valley). At first glance, one might be surprised to learn that this understated character was an essential contributor to the chaotic music scene that birthed bands like Operation Ivy, Blatz and Green Day.

After the show had ended, while everyone else slept off their hangovers or rotted all night at the 24-hour donut shop, Murray would be hunkered down in the makeshift darkroom set up in his kitchen, spending hours developing pictures of bands. He would later gather up all of the prints and shove them into a shoebox to bring to shows to share and sell for 15¢ a piece, the cost of the paper. (This was later raised to a quarter. Inflation, y’all.) While rifling through Murray’s shoebox, eager eyeballs went on the lookout for pictures of favorite bands or secret crushes, but more than anything else, people were hoping to find a photo of themselves. Being captured in a Murray picture was a stamp of approval. It was a confirmation that you had indeed been there. That you belonged.

That manifestation of belonging takes on various forms in the punk scene. It doesn’t matter how shy a person is, or how lacking in musical ability. Everyone has a role. And while bands have always enjoyed the spotlight, they’re just one part of a complex ecosystem. There are zine editors, promoters, the people who feed and house the touring bands, Steve List, the volunteers who sweep the floors and clean the toilets. These often unsung community heroes are the reason the punk scene has been able to function and evolve.

Why do this work that is neither glamorous nor rewarded? Sometimes community service is a calling. As Murray famously said, “I wanted to be more than just a spectator.” There are those people who see something that needs to be done and are compelled to do it. Surely no one embodies this more than Anna Brown, teacher, longtime East Bay punk, and Murray’s most bulldogged advocate, the person who consented to take on the monumental task of compiling, designing, and editing Hail Murray!