At Haines Gallery, artists Kota Ezawa and Taha Belal exhibit two engaging solo shows both involved in separate but similar investigations regarding the power of photographic images. In the front of the gallery, Ezawa’s The Curse of Dimensionality includes paper works, lightboxes, stereoscopic viewers, and a video — all produced over the past three years. Across these media and using his now-signature style, photographs are rendered as flat planes of color in a paint-by-numbers fashion. The Atmosphere from before the Step Down Returns to the Square, Belal’s first show at Haines, features intricately altered Egyptian newspapers, made in Cairo during the last year of turmoil. Though dealing with vastly different source material, both Ezawa and Belal question the inherent truth of the photographic image: as a representation of familiar space and proof of historically important events, respectively.

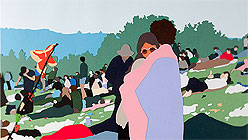

Ezawa’s show collects previously exhibited and new work into the categories of “light absorbing” and “light emitting.” The first category belongs to a salon-style grouping of framed cut paper works, each representing iconic historical and art-historical photographs, from a Becher water tower to the Woodstock couple embracing under a shared blanket. Underneath these works, a line of paper rectangles creates a color bar of sorts, evidence of the material process involved. Ezawa executes a similar move with his 2008 piece Handvote. Beneath the voters, used cans of lettering enamel are piled artfully on the floor.

Nature Scenes, Kota Ezawa, 2011.

This A to B relation is echoed throughout the exhibition, sometimes between two juxtaposed works, other times less obviously, as in the relationship between the video City of Nature and a series of stereoscopic viewers, Nature Scenes. In the latter, banal still images (a flying bird, a lurid sunset) begin flat, but when viewed through the lenses, pop into three-dimensional relief. Instead of appearing closer to reality, however, as the one antique example does, Ezawa’s images become all the more falsified — this version of “nature” is manufactured.

At the opposite end of the gallery, the six-minute video City of Nature brings the stereoscopic images into motion. Made by selecting clips from narrative films in which no human entered the frame, the video flows together in a seemingly logical fashion: at first it appears to be a documentary without a voice-over. An impulse to connect the scenes into a story of a specific habitat or species fails, however, when one cut shows dorsal fins, another a rushing river, and yet another a group of sleepy sheep. Timed to play simultaneously on three flat screens, this mechanical precision further stresses the images’ remove from an organic world into a highly constructed one.