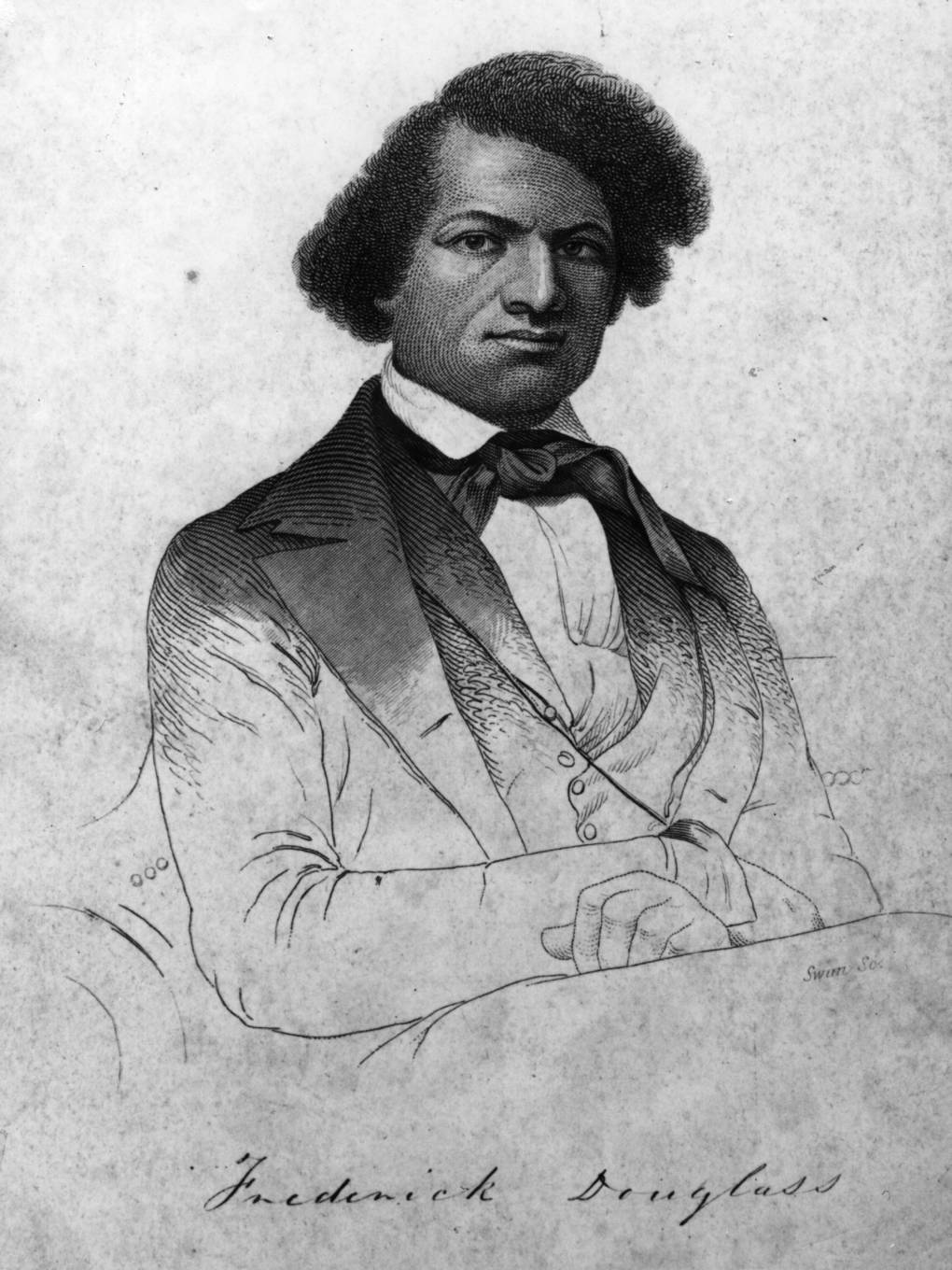

President Trump recently described Frederick Douglass as "an example of somebody who's done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice." The president's muddled tense – it came out sounding as if the 19th-century abolitionist were alive with a galloping Twitter following – provoked some mirth on social media. But the spotlight on one of America's great moral heroes is a welcome one.

Douglass was born on a plantation in Eastern Maryland in 1817 or 1818 – he did not know his birthday, much less have a long-form birth certificate – to a black mother (from whom he was separated as a boy) and a white father (whom he never knew and who was likely the "master" of the house). He was parceled out to serve different members of the family. His childhood was marked by hunger and cold, and his teen years passed in one long stretch of hard labor, coma-like fatigue, routine floggings, hunger, and other commonplace tortures from the slavery handbook.

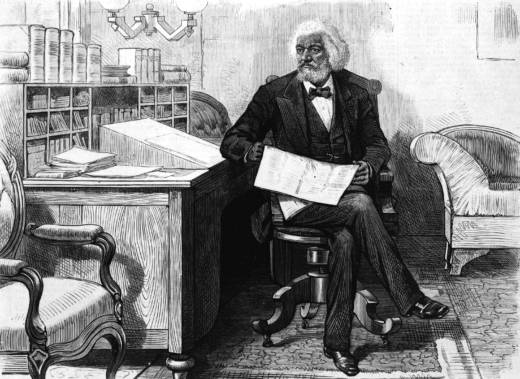

At 20, he ran away to New York and started his new life as an anti-slavery orator and activist. Acutely conscious of being a literary witness to the inhumane institution he had escaped, he made sure to document his life in not one but three autobiographies. His memoirs bring alive the immoral mechanics of slavery and its weapons of control. Chief among them: food.

Hunger was the young Fred's faithful boyhood companion. "I have often been so pinched with hunger, that I have fought with the dog – 'Old Nep' – for the smallest crumbs that fell from the kitchen table, and have been glad when I won a single crumb in the combat," he wrote in My Bondage and My Freedom. "Many times have I followed, with eager step, the waiting-girl when she went out to shake the table cloth, to get the crumbs and small bones flung out for the cats."

"Never mind, honey—better day comin,' " the elders would say to solace the orphaned boy. It was not just the family pets the child had to compete with. One of the most debasing scenes in Douglass' first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, describes the way he ate:

"Our food was coarse corn meal boiled. This was called mush. It was put into a large wooden tray or trough, and set down upon the ground. The children were then called, like so many pigs, and like so many pigs they would come and devour the mush; some with oyster-shells, others with pieces of shingle, some with naked hands, and none with spoons. He that ate fastest got most; he that was strongest secured the best place; and few left the trough satisfied."

Douglass makes it a point to nail the boastful lie put out by slaveholders – one that persists to this day – that "their slaves enjoy more of the physical comforts of life than the peasantry of any country in the world."