Though most of us are unfamiliar with the man behind the brand, we understand the name James Beard as synonymous with excellence in all things culinary. An annual event named after him has been honoring America's best chefs, restaurants and food-related media since 1990. The new film James Beard: America's First Foodie chronicles the life of the man Julia Child referred to as "the quintessential American cook," kicking off a "Chefs Flight" of four documentaries profiling Beard, Child, Alice Waters and Jacques Pépin for American Masters' 31st season Friday, May 19 at 9:00pm on KQED 9.

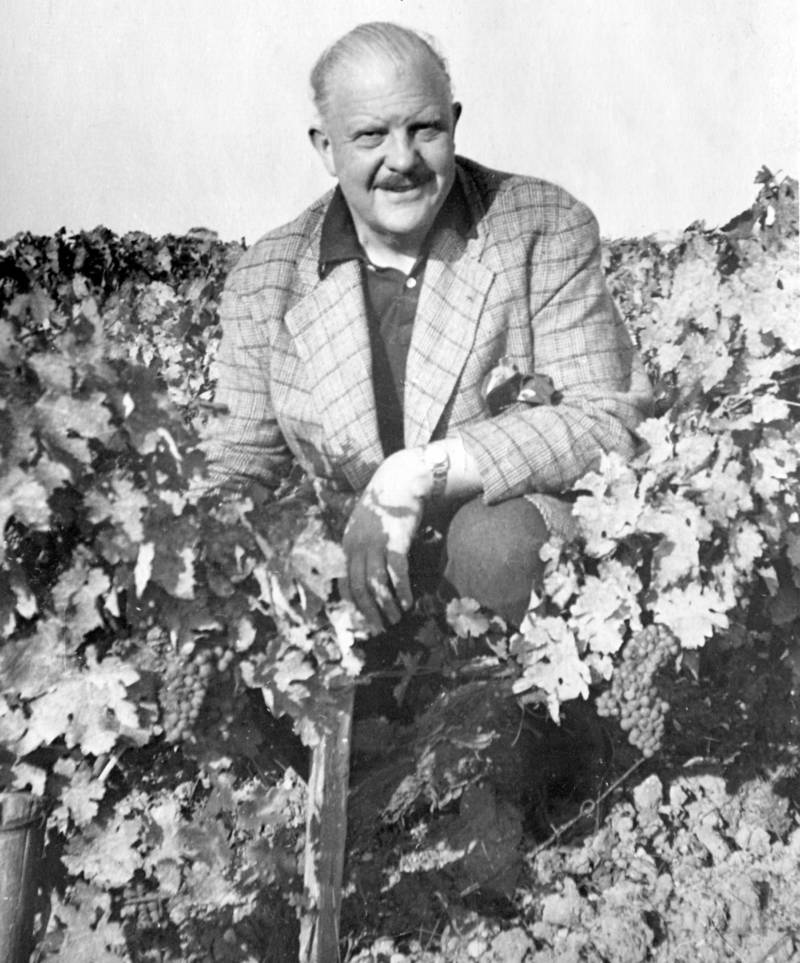

James Beard was born in Portland, Oregon at the dawn of the 20th century to a mother, Elizabeth, who owned a small hotel and was something of a local sensation, both for her cooking and for her liberated lifestyle. The early education she provided in buying and preparing fresh, local foods in season would become the guiding principle for the food movement her son later catalyzed. By his own account, the young Beard was as unrestrained by convention as his libertine mother, understanding at an early age that he was homosexual. He was expelled from Reed College, where he studied acting, for engaging in (then-illegal) same-sex activity. At 19, Beard headed to Europe to study opera, but ended up exercising his large appetite in the bistros of Paris, whose practices he taught to others when he returned to Oregon.

Beard moved to New York in 1937, surviving lean times by cooking for friends in exchange for his supper. From these gatherings came his first success. He and William Rhode (later the editor of Gourmet magazine) started a catering business called Hors D'Oeuvre, Inc, which provided the recipes for his first cookbook, Hors d'oeuvre and Canapes, published in 1940. He followed that success with Cook It Outdoors, "believed to be the first serious book on outdoor cooking," according to his New York Times obituary.

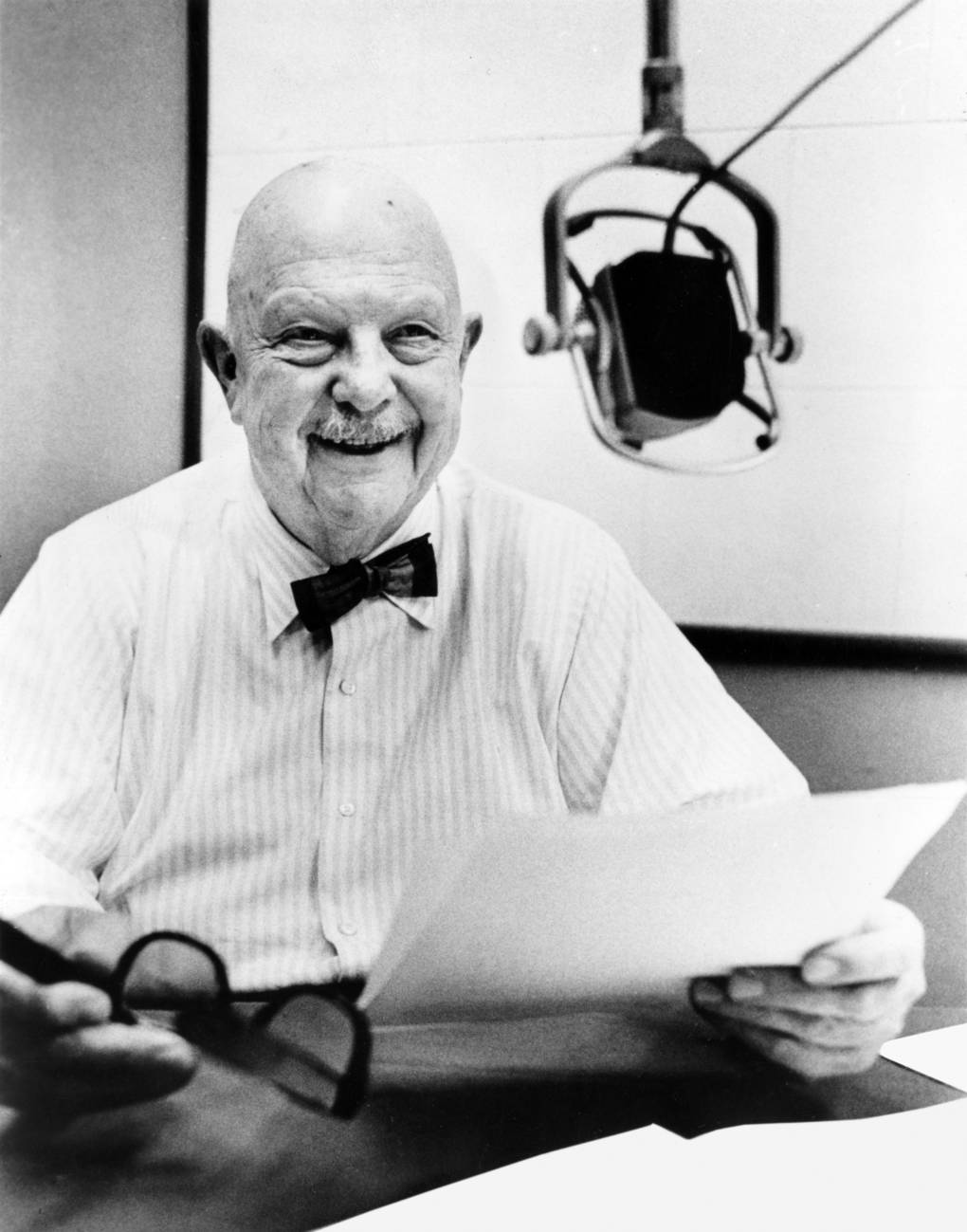

In 1946, Beard hosted I Love to Eat for two seasons on NBC, introducing cooking to TV. He founded The James Beard Cooking School in 1955, teaching people around the country how to cook for the next thirty years. The school eventually settled in Seaside, Oregon, where he taught each summer using the same fresh ingredients his mother prepared in his youth, and in the kitchen of his Greenwich Village brownstone in Manhattan, which also became a popular hangout for the rich and famous. Beard's good friend Julia Child lobbied for the preservation of his Manhattan home shortly after he died in 1985 and, through the efforts of Peter Krump, a former student, and a cadre of well-connected friends, the James Beard Foundation was born.