"The Etruscan industry started to take off," says McGovern. And within 200 years, he says, "they did the same as the Phoenicians: building ships and carrying their wine over to southern France."

To figure out just when France's wine culture began, McGovern and his colleagues analyzed organic residues that had seeped into jars recovered from the ancient French port city of Lattara (now known as Lattes). The jars were distinctly Etruscan in style, which told the researchers that they had been imported. As the researchers report this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their tests confirmed the jars had contained wine from 500 to 475 B.C.

That act of importation soon led to imitation, the authors say: Once the French got a taste of the Etruscans' intoxicating drink, they wanted in on the action. It was "a relatively short time" (100 years or so) before grapevines were transplanted and local wine production got underway in southern France — probably "under Etruscan tutelage" at first, McGovern and his colleagues write.

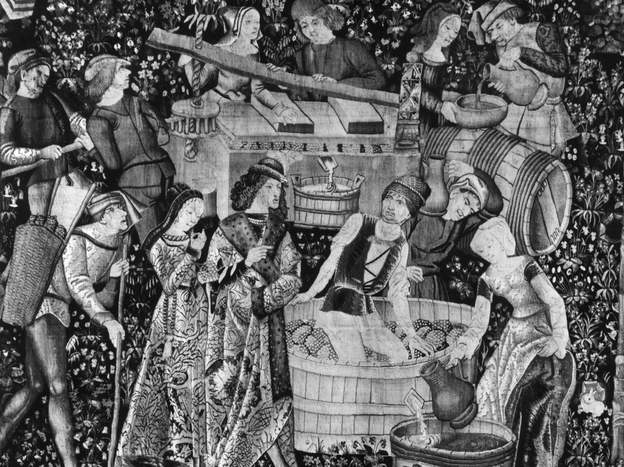

The researchers found biomarkers for grapes in the limestone of a pressing platform (also from Lattara) from about 425 B.C. Not only did this indicate that it was used as a wine press, and that the locals were vinting their own wine by that time, but it also confirmed the tool as the earliest chemically identified wine press. It's possible the French were making wine even earlier than this, but McGovern's research provides the first chemically confirmed date.

McGovern — who has spent much of his career tracing viniculture history — says that wine culture drove cross-civilization interactions. (One might say it still plays a pretty important role in easing social interactions.)

"When [rulers] get interested and they start incorporating wine into their everyday lives, then it works its way into the religious ceremonies," he says. "And then it filters down to the average person after a while. It's a lot like the New World spread of wine culture out to California, Australia, New Zealand and so on."

But perhaps the wine we toast with today would taste vastly different if it hadn't been for those pioneer French vintners more than two millennia ago.

"During the Middle Ages (and later) — especially in the monasteries — the French refined winemaking in such a way that it became the world's standard," he says. "As such, when New World wineries were established, they almost always transplanted French cultivars."

Copyright 2013 NPR.