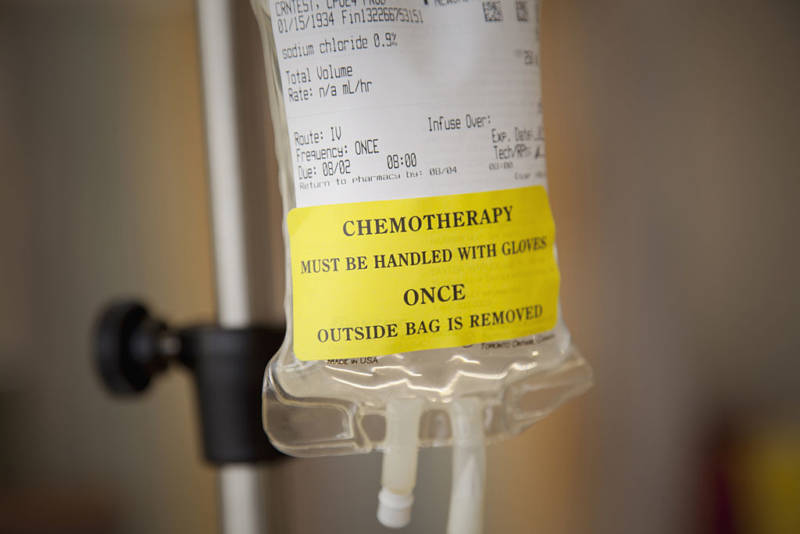

Some early-stage, post-operative breast cancer patients meeting a certain genetic profile can avoid potentially dangerous and expensive chemotherapy with only a slightly lower survival rate, and without the cancer spreading, a major study published in The New England Journal of Medicine Wednesday has found.

The study said that 46 percent of subjects who were classified as high-risk by traditional clinical criteria but low-risk according to their genetics could skip chemo and expose themselves to just a slightly greater risk – 1.5 percent -- of the cancer metastasizing after five years.

Those who received chemo had a 95.9 percent rate of success after five years, compared to 94.4 percent of those who did not get the treatment.

In other words, the difference between opting for chemo or not is so small that "You would have to treat 100 of those [patients] with chemotherapy for the benefit of one," said Dr. Laura van't Veer, one of the leaders of the breast oncology program at the University of California, San Francisco, who helped develop the test that the researchers used to determine the genetic risk level of recurrence for each patient.

That still may be enough of a difference for some patients and their doctors to choose chemo. In an editorial that accompanied the study in the NEJM, Dr. Clifford A. Hudis, chief executive officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and Dr. Maura Dickler, a researcher who also treats breast cancer patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, said the decision whether to undergo chemo or not won't be a slam dunk, even with the new information provided by the test.

"(A) difference of 1.5 percentage points, if real, might mean more to one patient than to another," they wrote. "Thus, the stated difference does not precisely exclude a benefit that clinicians and patients might find meaningful."