Asthma attacks come with little warning and are often triggered by invisible particles in the air. Now, thanks to advances in Bluetooth technology, smartphones have become the newest weapon in the fight against asthma.

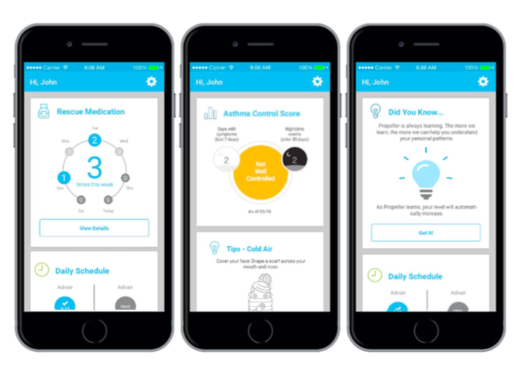

Propeller Health, a Wisconsin-based company, wants to help those with respiratory problems by supplementing medicine with technology. The firm has wired an inhaler with a Bluetooth transmitter to communicate with an asthma patient’s smartphone. This sensor activates when the inhaler is pressed, setting into motion a process that records the exact time and location of a patient’s asthma attack on a smartphone app. Doctors can view this data and see, not only how frequently the patient suffers attacks, but also tease apart the environmental factors that caused the distress.

“We see firsthand the value of collecting data, and so we see this as being the clear future of health care,” said Chris Hogg, the COO of Propeller Health. “[This technology] helps health care providers prioritize patients. With all the information coming off of the connected devices, [doctors] can really see who should be focused on.”

Smart inhalers are part of an emerging trend in medical technology known as “connected health.” Major tech firms have introduced ventures like Apple Health, a part of the iOS operating system that groups together biometric data recorded by apps and accessories. Meanwhile, medical equipment firms are installing internet connections on their devices, such as Continuous Positive Airway Pressure sleep machines, glucose meters and blood pressure monitors.