That statement was seconded by other scientists.

"It opens up a new area of research," says Dietrich Egli, a Columbia University biologist who studies stem cells and was not involved in the study. "Understanding early human embryonic development is of great importance, and gene-editing is a powerful tool to answer questions that will ultimately improve human health."

But the research is renewing a long, intense debate about whether it's ethical to make changes in the genes in eggs, sperm or very early embryos that would be passed down to succeeding generations. While using gene editing for basic research about human development may be useful, critics worry it could lead to attempts to create genetically modified babies.

"The concerns are that we would be opening the door to fertility clinics vying to offer gene-editing to make future children taller or stronger or whatever they wanted to market," says Marcy Darnovsky, who heads the Center for Genetics and Society, a genetics watchdog group. "That could put us into a situation where some children were perceived to be biologically superior to other children.

The study comes just weeks after another team of scientists reported the group had for the first time edited the DNA in human embryos to correct a genetic defect that causes a heart disorder.

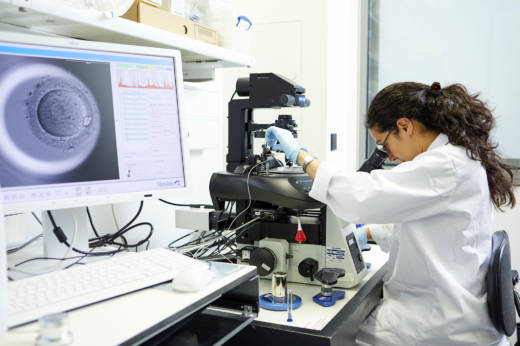

The new research was led by Kathy Niakan, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London. Niakan's team used a powerful gene-editing technique known as CRISPR to disable a gene that produces a protein known as OCT4. The procedure was performed in 41 embryos donated by women undergoing treatment for infertility.

In the study, more than 80 percent of the embryos with the disabled gene failed to develop into a blastocyst, a ball of 200 cells that is the stage when embryos are usually implanted into the womb during in vitro fertilization (IVF). Many cases of infertility occur because embryos fail to reach this stage.

"That tells us that OCT4 is really important for the development of a human blastocyst," Niakan told reporters during a briefing.

"By understanding the key genes that are involved in the development of the blastocyst, this can really inform our understanding of this important, critical window of human development," Niakan says.

The experiments also show that the gene is involved in forming the cells that eventually become the placenta, the organ that nourishes a developing embryo in the womb, the researchers reported.

In addition, OCT4 helps embryonic stem cells specialize into various tissues, which could help scientists figure out how to turn stem cells into replacement cells, tissues and perhaps entire organs to treat diseases, Niakan says.

In an unexpected finding, the researchers discovered the gene functions differently in human embryos than in mouse embryos. That shows the need for experiments on human embryos and not just animal embryos, the scientists say.

"This is opening up the possibility of using a really powerful, precise genetics tool to understand gene function," Niakan says. "We would have never gained this insight had we not really studied the function of this gene in human embryos."

Jennifer Doudna, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who led efforts to develop CRISPR, agrees.

"One of the most fundamental aspects of becoming human is, how do egg and sperm cells combine to form embryos that develop into a person?" Doudna says. "So understanding the genetic basis for that is, in my view, one of the fundamental aspects of developmental biology — or all of biology in a way."

In 2015, Chinese scientists sparked an uproar when they reported attempts to use CRISPR to edit human embryos. And in 2016, the British government approved editing of human embryos for research purposes.

With the British government's approval, Niakan began her experiments. Scientists in Sweden have begun similar research.

In February, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine concluded that editing DNA in humans could be permissible in certain circumstances. That has critics like Darnovsky worried.

"In a world already plagued by distressing levels of inequality, that seems like a very bad idea," Darnovsky says. "We don't want to add ideas that some people are biologically better and some people are biologically inferior to others. That is an idea that has led to horrific abuses throughout history."

But Niakan defends the work, saying she is only interested in making fundamental discoveries about basic human biology.

"As with any technology, as with any tool, it can be used for a variety of different purposes," Niakan says. "We're choosing to use it to uncover critical roles of genes in development that can increase our knowledge about how human embryos develop."

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))