For more than half a century, I believed that something in my character or emotions was responsible for the pain in my gut and my bloody diarrhea. I now know that’s not true, thanks to my doctors and to my deep dive into the history of this disease.

In my lifetime, a revolution has occurred in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Unearthing its history has angered me, not so much because of how I was deceived but for the shattered lives of fellow sufferers. Even today it leaves people isolated, subject to therapeutic trial and error, fearful of long-term complications such as cancer, and stigmatized. One of the goals of my research is to make sure they don’t feel they are to blame for their disease.

The radical idea of using lobotomy to treat ulcerative colitis arose from a theory in vogue at the time: The disease was psychosomatic, meaning it originated from mental or emotional causes. This concept evolved from ancient observations that emotions can cause physical changes. Think sweating under stress, stomachaches before marriage, battlefield diarrhea, and the like.”Emotions and Bodily Changes,” a persuasive collection of anecdotes published in 1935 by psychiatrist Helen Flanders Dunbar, helped set the stage for viewing many illnesses as psychosomatic.

The theory that ulcerative colitis was psychosomatic goes back to a single article published five years earlier in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences by Cecil Murray of Columbia University, who was a medical student at the time. He claimed that he found common traits in a dozen patients with ulcerative colitis. All were childish, the men were tied to their mothers’ apron strings, and they all got sick right after “a difficult psychologic situation.” Psychotherapy, he wrote, could help them.

Murray’s theory spread like wildfire through the gut medicine community. It was fueled by physician ignorance and impotence, the habit of looking askance at patients whose symptoms could not be explained, and the arrival in the U.S. of German psychoanalysts who were disciples of Sigmund Freud. They believed that emotions could make you sick, wrote Robert Aronowitz and Howard Spiro in their 1988 article “The Rise and Fall of the Psychosomatic Hypothesis in Ulcerative Colitis.”

No disease was more ripe for a Freudian fix than ulcerative colitis. Uncontrolled diarrhea could be blamed on a mother’s faulty potty training. By the late 1940s, dozens of medical journal articles described people with colitis as immature, fastidious, mother-clinging obsessives.

There were also no good treatments at the time for a disease that killed up to 30 percent of those it struck. Medications were few and largely ineffective, and the only known cure was the risky removal of the colon — at the Lahey Clinic, the surgery itself killed 22 percent of the patients who underwent it — which made the patient a shamed invalid with an uncontrolled fecal stream dribbling out of a red abdominal stump.

Not everyone bought into the psychosomatic theory. In a spirited 1947 conference debate, quoted in Aronowitz’s unpublished 1985 M.D. thesis at Yale University, Sarah Jordan, head of gastroenterology at the Lahey Clinic, described a typical patient as a “young vigorous human being with all-too-often superior type of striving, ambitious personality — the type of young person that we all like to have as sons and daughters.”

To which Yale’s Albert Sullivan, one of the most prolific cheerleaders of a psychosomatic origin for ulcerative colitis, retorted: “I have yet to see a patient with non-specific ulcerative colitis that I would have as part of my family.”

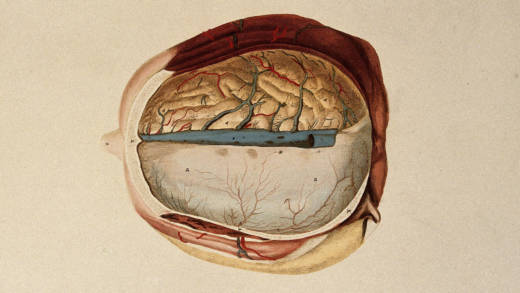

It was only a matter of time before the psychogenesis concept produced bizarre experiments. If the brain and its “nervous tensions” could be disconnected from the gut, the thinking went, then the gut could heal. At several major hospitals, patients were locked away in psychiatric wards and subjected to psychotherapy, electroshock, novocaine injections into the brain, and slicing sections of the vagus nerve, which connects the brain with the intestinal tract.

The first mention of performing a lobotomy to treat colitis that I could find appeared during a 1948 postmortem conference at the University of Iowa. A 23-year-old housewife, wasted and drained to a skeleton, had died from ulcerative colitis, and physicians pondered what more they could have done for her. Citing the growing literature on psychogenesis, a neurosurgeon suggested a lobotomy. The proposal touched off soul-searching among the doctors at the table, although there is no record that surgeons at the university followed through on the idea.

Three years later, the Lahey team performed the first known lobotomy for ulcerative colitis on patient zero, an only child born in 1916. She had previously undergone electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock treatments, a temporary rerouting of the small intestine (called an ileostomy), and psychotherapy. According to her Lahey doctors, the lobotomy was a success.

In the decade that followed, dozens of colitis patients were given lobotomies in the U.S., Canada, and several European countries. A 1955 literature review found mixed results in the U.S., with one or two successes and other cases that “have apparently not noted good results.” In 1964, the Belgian medical journal Le Scalpel reported that over the course of 10 years “positive results” were observed in two-thirds of 50 lobotomies done on people with ulcerative colitis “without impact to the psyche.”

At the University of Oklahoma, surgeons performed five lobotomies on three women and two men who had been diagnosed with mental illness as well as ulcerative colitis. The effects on the three women’s colons “were strikingly beneficial,” as their number of bowel movements returned to normal, according to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association. But both of the men died of complications. I was able to track down the sons of one of them, Roy Mixer, who died after undergoing two lobotomies in 1954. They remembered twin scars on their dad’s skull and his empty staring.

“He was a guinea pig. He wasn’t my dad,” Richard Mixer told me.

Lobotomies for ulcerative colitis, and for mental illness, were halted in the late 1950s because of outrage at the barbarity of the procedure and the emergence of new drugs — antipsychotics for mental illness and corticosteroids for colitis. The era of the psychosomatic genesis of ulcerative colitis should have ended in 1990 when an American Journal of Psychiatry review of 138 studies that had linked ulcerative colitis with psychiatric factors found “serious flaws” and bias in 131 of them. Of the seven studies the authors determined were solid systematic investigations, all seven failed to find a link between psychiatric factors and ulcerative colitis. And yet, the reviewers added, “a substantial number of authors continue to subscribe to a psychosomatic model.”

Only one physician that I know of, renowned gastroenterologist Joseph Kirsner of the University of Chicago, apologized publicly in a speech at a German conference for getting drawn into the dark alley of psychogenesis, according to David Rubin, a professor of medicine and Kirsner’s successor at Chicago. The comment, made late in Kirsner’s life, was not published.

Although the belief that an individual’s character or emotions causes ulcerative colitis was discredited and has largely been abandoned by gastroenterologists, many people living with the condition today are still shadowed by the notion that their disease begins, worsens, or abates in their minds, and that because emotions can be controlled, they ought to be able to heal themselves.

“It’s so easy for people to analyze a physical problem and blame it on a psychological issue that is going on in your life,” according to Judith Alexander Brice, a Pittsburgh psychiatrist and poet who detailed her battle with inflammatory bowel disease and attitudes among her peers in an essay published in the book “When Doctors Get Sick.”

Before Brice had her colon removed in 1982, doctors in her psychiatric community suggested that she was “too anxious or too depressed,” and would not be sick “if I had a different psychological constitution,” she said in an interview. “It was enraging, demoralizing and it made me feel so estranged from people.”

Just last month, in a private Facebook group devoted to ulcerative colitis, Andrea Thornton Boggs, a mother from Illinois who was diagnosed at age 4, wrote: “I was a very timid and sensitive child and the doctors at the time attributed my UC to that. I was always told to relax and loosen up and I would feel better. Some of my family members still believe it’s all in my head. It causes me to doubt myself in every way.”

I didn’t react that way in 1962 when, as an 18-year-old farm boy and college freshman, I read in a medical textbook that my ulcerative colitis was psychosomatic. I took it as fact and stuffed it inside. For the next half century, I assumed that I was to blame, at least in part, for bringing on my symptoms.

Five years ago, I mentioned this to my family doctor. “We owe you an apology,” he said, putting his hand on my belly. “That’s not even taught anymore.”

Wrestling with that revelation, I decided to research my darkest secret, a miserable disease that I finally cured by asking a surgeon to remove my colon.

Here’s my hope: that some reader will know what happened to patient zero, whose treatment could be the opening chapter in my story of ulcerative colitis, a decimating disease whose shameful history deserves to be told.

Jim Carrier, an award-winning journalist, is a member of the University of Vermont Committee on Human Research in the Medical Sciences. He is writing a history of ulcerative colitis and its treatment.

![]()