"The data are very provocative, but fall short of showing a direct causal role," he says. "And if viral infections are playing a part, they are not the sole actor."

Even so, the study offers strong evidence that viral infections can influence the course of Alzheimer's, Hodes says.

Like a lot of scientific discoveries, this one was an accident. "Viruses were the last thing we were looking for," Dudley says.

He and a team of researchers were using genetic data to look for differences between healthy brain tissue and brain tissue from people who died with Alzheimer's.

The goal was to identify new targets for drugs. Instead, the team kept finding hints that that brain tissue from Alzheimer's patients contained higher levels of viruses.

"When we started analyzing the differences, it just sort of came screaming out at us from the data," Dudley says.

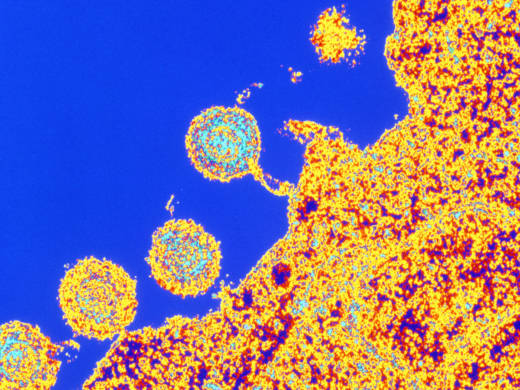

The team found that levels of two human herpes viruses, HHV-6 and HHV-7, were up to twice as high in brain tissue from people with Alzheimer's. They confirmed the finding by analyzing data from a consortium of brain banks.

These herpes viruses are extremely common, and can cause a skin rash called roseola in young children. But the viruses also can get into the brain, where they may remain inactive for decades.

Once the researchers knew the viruses were associated with Alzheimer's they started trying to figure out how a virus could affect the course of a brain disease. That meant identifying interactions between the virus genes and other genes in brain cells.

"We mapped out the social network, if you will, of which genes the viruses are friends with and who they're talking to inside the brain," Dudley says. In essence, he says, they wanted to know: "If the viruses are tweeting, who's tweeting back?"

And what they found was that the herpes virus genes were interacting with genes known to increase a person's risk for Alzheimer's.

They also found that these Alzheimer's risk genes seem to make a person's brain more vulnerable to infection with the two herpes viruses.

But just having herpes virus present in the brain isn't enough to cause Alzheimer's, Dudley says. Something needs to activate the viruses, which causes them to begin replicating.

It's not clear what causes the activation, Dudley says, though he suspects some sort of change in the internal functions of brain cells.

Once the viruses do become active, they appear to influence things like the accumulation of the plaques and tangles in the brain associated with Alzheimer's. "They are sort of throwing a wrench in the works," he says.

The herpes viruses also seem to trigger an immune response in certain brain cells, Hodes says. These cells are part of an ancient immune system that has previously been implicated in Alzheimer's.

Most previous efforts to prevent or treat Alzheimer's have involved trying to reduce the plaques and tangles associated with the disease. Those efforts have failed to improve brain function even when they accomplished their immediate goal.

Those "distressing and disappointing failures" suggest it's time for some new approaches, Hodes says. And the new study suggests at least two.

One is to give antiviral drugs to people with high levels of herpes virus in their brains. The Institute on Aging is already funding a study to test this approach in people in the early stages of Alzheimer's, Hodes says.

Another approach is to prevent the brain's immune cells from reacting to the virus in ways that accelerate Alzheimer's, Hodes says. That's tricky, he says, because simply disabling the brain's immune cells could be harmful.

Even so, Hodes is optimistic.

"The more we learn about the disease process and the more targets we can address," he says, "the greater the probability we are going to slow or prevent the progression of Alzheimer's disease."

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))