Most cancer patients are haunted by the same two questions:

"Why me?"

"Why now?"

Not Ashley Walton.

Walton, 34, actually feels lucky advanced melanoma struck when it did.

Most cancer patients are haunted by the same two questions:

"Why me?"

"Why now?"

Not Ashley Walton.

Walton, 34, actually feels lucky advanced melanoma struck when it did.

“If I had been diagnosed five years prior, who knows if I would be here," she says.

Stage 4 melanoma used to be a death sentence. The disease doesn’t respond to radiation or chemotherapy, and patients survived, on average, less than a year.

But over the last decade, doctors are successfully using a new approach, one significantly different than the treatment options available for the last 150 years.

Instead of burning or poisoning cancer cells, new medicines unleash the body's natural defenses to fight them.

This treatment is called immunotherapy.

Beating the Odds

When Walton was 26, she found a mole on the back of her hip.

"It started morphing into this ugly, dark, bleeding thing," she says, grimacing. "I just knew something was wrong."

Doctors surgically removed her tumor. But a couple of years later, she discovered a tiny lump in her abdomen. It felt like a popcorn kernel, and within a few weeks grew to the size of a walnut.

A biopsy revealed she had stage 4 melanoma.

Walton searched online for information about the disease. She recalls the moment she discovered the average survival rate: six to nine months.

"I remember sort of losing my hearing, almost losing my vision to where I felt like I was in a tunnel," she says.

But when she consulted with her oncologist, Dr. Adil Daud of UC San Francisco, he had consoling news.

“He told me if there's any time to have a melanoma -- right now is a pretty good time to have it -- because there's a lot of stuff opening up to you," she says.

Dr. Daud was referring to immune checkpoint inhibitors, which he says are increasing survival rates by at least threefold. These cancer drugs help the immune system do what it’s supposed to -- fight pathogens.

Normally the immune system recognizes disease-causing organisms. But cancer cells are unusual because they go undetected as harmful. Immune checkpoint inhibitors make them visible for attack.

Treatment Earns Nobel Prize

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the first immune checkpoint inhibitor in 2011 marked a breakthrough in the field.

The technology behind Ipilimumab, which is branded as Yervoy, was developed in a UC Berkeley lab in the 1990s, by a student named Matthew Krummel, now an immunotherapy researcher at UCSF.

“I was a very frustrated graduate student for a few years, trying to develop an antibody that would do something," Krummel says.

He wanted to influence how cells behave. After many long nights, Krummel noticed one antibody successfully manipulating the movement of immune cells.

“You can drive them like a car; you can accelerate them; or you can brake them," Krummel says. "And then it was really like playtime.”

He injected the antibodies into mice with cancer. In the very first set of experiments, their tumors shrunk.

Earlier this month, Krummel’s thesis advisor, James Allison, won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for their lab's work on immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Years of Harrowing Treatments

When Walton started immunotherapy treatment, including Ipilimumab, the 90-minute drips were followed by side effects like fever, diarrhea, rash, vomiting and gastritis. This is not uncommon in immunotherapy, as the drugs can put a patient’s immune system into overdrive provoking an attack on healthy cells, tissues and organs.

Walton’s tumors initially shrunk, but within six months, new tumors cropped up, in her abdomen. Her oncologist then ran through the list of available drugs, moving on as each one, sometimes tried in combination, in turn failed to deliver the knockout blow.

“It's absolutely exhausting emotionally and physically to know that there's no option for you,” says Walton. “Those were the days when I felt like I will probably die from this, and I’ll die young.”

Finally, eight years later, she heard the magic word: remission. Dr. Daud isn't sure if it was the buildup of multiple immunotherapy drugs or some new combination that did the trick.

“There are so many advancements being made in the field of immunotherapy that even if [one] doesn't cure you, it gets you to the next big thing,” says Walton.

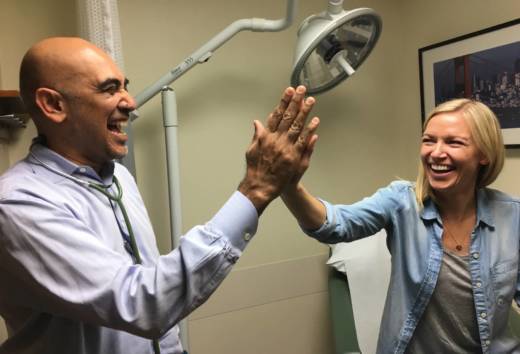

Now that she has been off immunotherapy for 10 months, Walton tentatively asked Dr. Daud something that had been her mind for a long time.

"So, what do you think about pregnancy or trying to start a family?" asked Walton.

"I think this is a good time to get pregnant, actually," responded Dr. Daud.

Both doctor and patient could barely contain their glee, punctuating the question-and-answer session with happy giggles. Walton crosses her fingers and smiles. Throughout her treatment, doctors warned that getting pregnant would be too dangerous. But Daud now trusts her body's ability to support a child.

A Hopeful Future

Stories like Walton's are sparking a lot of excitement among oncologists.

"So imagine when we’ve gone from a time when we had nothing to offer, to today, and they are talking about a cure for some patients with advanced melanoma," says Dr. Leonard Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

Scientists and major pharmaceutical companies are waging huge bets on immunotherapy. There are currently about 1,000 active trials to develop the next miracle drug. Lichtenfeld is optimistic, but he is also cautious about adding to the hype.

“We don’t know in how many cancers they are going to be effective,” he says. “And we still don’t know how to harness the maximum benefit from these drugs by, say, using them in combination with other drugs.”

Currently, 40 percent of advanced melanoma patients still do not respond to immunotherapy. The statistics are even worse for other cancers.

“It is still very common to not have immune treatment work at all,” says Dr. Daud. “Across different tumor types, only about 20 percent of patients with cancer respond to today's immunotherapy, so the numbers are much more sobering."

He hypothesizes that age, gender, concurring autoimmune diseases, or even gut bacteria may influence patient responsiveness, but he says we know very little about these factors.

“I think there's a lot of fundamental questions about the immune system that we just simply don't know the answer to,” says Daud.

“And yet I do foresee a day when we use other types of treatment infrequently to treat cancer, and most cancers will be treated with immunotherapy. But we still have a long ways to go.”

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.