For instance:

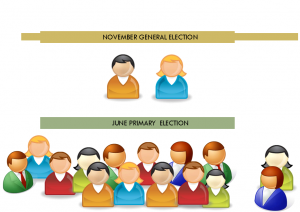

If two Republicans, two Democrats, and one Libertarian are all running in a primary election for a state assembly seat in your district, you can now vote for any candidate you want, regardless of your own party affiliation. And no matter how many different candidates from different parties are in the primary race, only two candidates will make it to general election.

One of the interesting potential outcomes of this new system is that some primary races could result in two candidates from the same party facing each other in the general election (if they respectively get the first and second highest amount of votes in the primary).

And unlike the old system, third party candidates who aren't within the top two in the primary, won't be on the ballot in November. The new rule also eliminates the possibility of adding on write-in candidates in the general election (again, with the exception of the presidential election).

For more on how the process works, Alameda County provides a good explanation with visuals.

What's the point of this?

Prop 14 was championed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger as a means of reforming California’s bitterly divided political system and breaking the gridlock in Sacramento. With a war chest of nearly $5 million, proponents of the measure made the case that an open primary process would force candidates to appeal to voters across party lines and reach a larger swath of the public, resulting in a less divided class of elected officials. Backers also argued that increasing the number of choices on the ballot would boost voter turnout and give more political voice to California’s growing contingent of independent voters (who make up about 20 percent of the electorate).

On the other side of the debate, both the state’s Republican and Democratic party leaders, as well as a number of smaller parties and big labor unions, strongly denounced the measure on grounds that it would make primary campaigns significantly more expensive (because candidates would need to appeal to voters across party lines) and thus benefit the richest candidates with the most name recognition. Opponents also argued that it would decimate the authority of individual political parties and all but eliminate opportunities for third party candidates to advance to the general election (remember that in the old system, one candidate from every party running in the primary was was guaranteed a spot in November).

In the end, though, nearly 54 percent of voters approved the measure, an indication of the public’s growing discontent with California’s political establishment. Some analysts, however, suggested that many of the voters supporting the measure may not have fully understood what they were voting for. And interestingly, San Francisco and Orange County, on opposite ends of California’s political spectrum, were among the only counties to oppose it.

Déjà vu?

No -- just California politics.

In 1996, voters approved Proposition 198, which instituted the “blanket primary.” The system was similar, in that voters could choose any candidate regardless of party affiliation. But it still resulted in one candidate from each party advancing to the general election.

The system was challenged in federal court and ultimately struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 7-2 decision on the basis that it violated a political party's First Amendment right of association.

More recently, another attempt to institute open primaries in California appeared on the 2004 ballot, but got the smack-down.