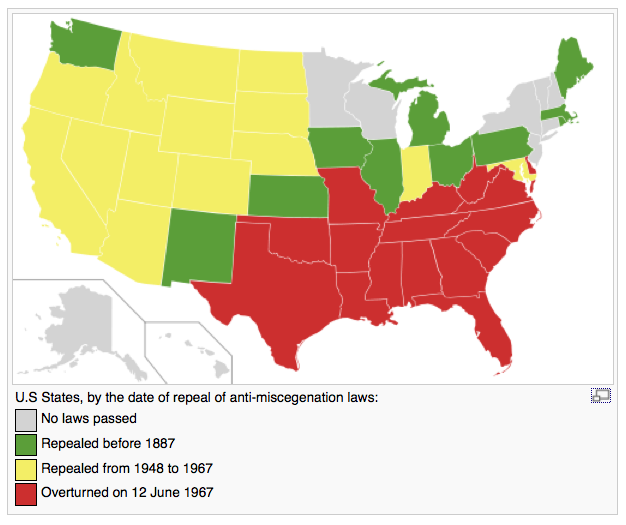

Interracial marriage was banned in nearly a third of all states up until 50 years ago.

That changed overnight following the Supreme Court's June 1967 ruling in Loving v. Virginia, a landmark case concerning an interracial married couple living in Virginia, one of the many mostly southern states that still enforced anti-miscegenation laws. (Virginia, it turns out, hasn't always been for lovers.)

In its unanimous decision, the Court -- led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former California governor -- ruled that anti-miscegenation laws violated the Constitution's Equal Protection Clause. The court ruled along similar lines in 2015, when it moved to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide.

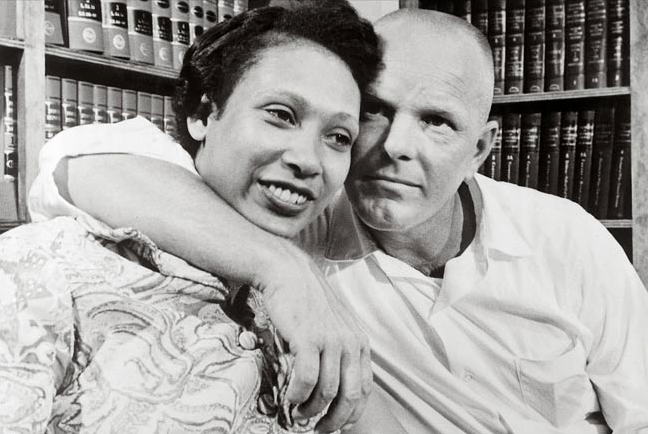

The plaintiffs

In 1958, Virginia residents Mildred Jeter, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, crossed into Washington, D.C. to get legally married . Soon after returning to Virginia, police raided their home in the middle of the night, arresting the couple on felony charges for breaking the state’s anti-miscegenation law, known as the Racial Integrity Act.

The two pleaded guilty in state court in January 1959 and were sentenced to a year in prison unless they agreed to leave the state for 25 years. In explaining his verdict, trial judge Leon Bazile wrote:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

The Loving's moved to Washington, D.C., where their marriage was legally recognized. A bricklayer and homemaker, the couple had little intention of becoming activists, but wanted the option of returning to Virginia.