At Avalon, there are 17 teachers and 190 students, 35 percent of who are recognized as special-needs. Bakken is one of the teachers, and in addition to teaching, she has designated time to tend to actually running the school. She has a hand in deciding everything from class curriculum, teachers’ salaries, budgets, benefits, whom to hire and fire.

The model has worked well for this school: Avalon has a 95-100 percent teacher-retention rate, the last teacher having left two years ago because she retired. And because their teachers tend to stick around, they all know that all the hard work they put into their strategic planning will be carried out by teachers who have complete buy-in and are invested in seeing it succeed.

Those interested in Avalon’s state test scores can note that the school has a higher rate of proficiency than St. Paul public schools, Bakken said, despite the fact that more than one-third of their students come from difficult backgrounds, including homelessness, substance abuse, being disengaged in school, and falling far behind in school work. “We’re not just taking the ‘cream from the top,’” she said in reference to criticisms that high-achieving charter schools pick and choose high-achieving students. “We have big cross section of students.”

But high test scores are not this school’s main objective. Putting power in the hands of teachers also means that students have much more control over their learning. The school takes a student-led, project-based approach to the curriculum, and has created a “constructive culture with student power at the center where they’re learning a framework for governance,” Bakken said. (Check out last year's students' projects).

“We’re modeling democracy at work, with self-directed projects, where students can mediate conflicts, make laws, and contribute to [school policies],” she said.

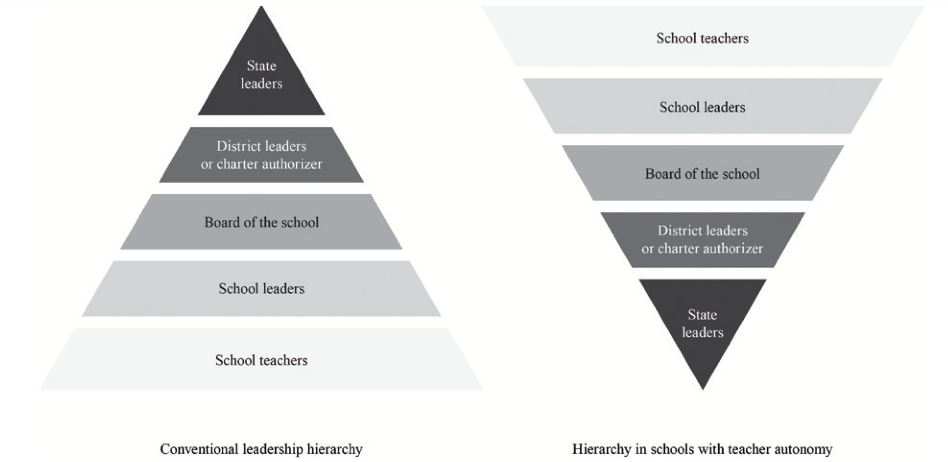

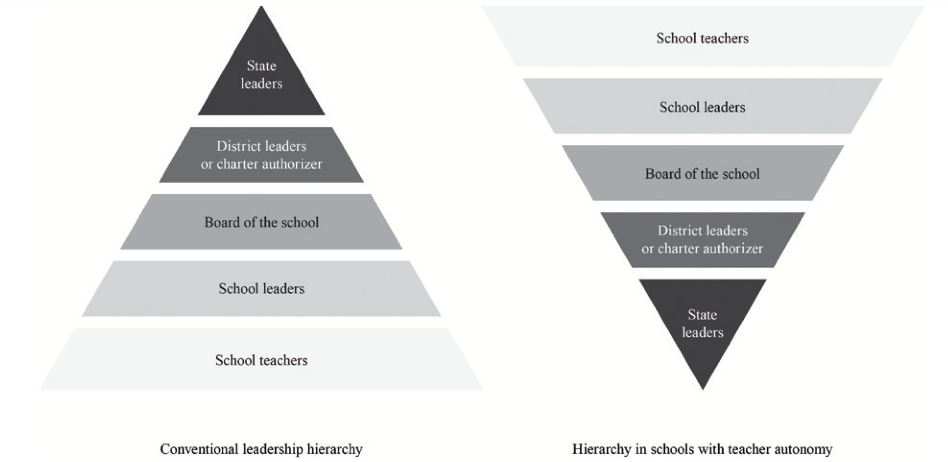

Students become accountable for their experience, and become agents of their own learning. If teachers feel powerless, then their students feel powerless too. But if a student can go to a teacher, knowing that they have a hand in making a decision that will have a direct impact, then students feel they have power too.

MORE POWER, MORE WORK

Though it’s gratifying in many ways, it’s not an easy path, Bakken said. And paradoxically, the benefits happen to be the same as the challenges.

“I’m constantly learning things, but I’m also constantly learning new things,” she said.

Avalon doesn’t have a district central office that can interpret new policies, and when the state budget is in crisis, the teachers have to figure out what steps to take to stay solvent. What’s more, collaboration doesn’t always come naturally -- it takes practice and work. “I enjoy being able to work to get to the best solution possible, but it can be time consuming,” she said. “Sometimes I feel like I have 26 other bosses.”

When it comes to teacher evaluations, the staff “police each other,” Bakken says. Plus, they hire coaches to observe them, and work with a personnel committee on those specific issues that come up. “We get a lot of feedback from each other,” she said.

When it comes to teacher evaluations, the staff “police each other,” Bakken says. Plus, they hire coaches to observe them, and work with a personnel committee on those specific issues that come up. “We get a lot of feedback from each other,” she said.

Xian Barrett, of VIVA Teachers, which works to increase teachers’ participation in making policy decisions about public education, pointed out a key point in making this work-by-consensus successful: “If you have trust in a room, consensus works much more effectively,” he said.

And it’s this level of collaboration and equality in running the school that gives teachers’ the voice they’ve been yearning for.

“The more power you give away, the more power you have,” Barrett said.

It’s also important to note that, although there's a support network and plenty of advice to make a school teacher-powered, there’s no prescriptive blueprint. “There’s no one telling you, ‘You’re going to do this and do it this way,’” Bakken said. “Teachers have to develop it organically. “

In fact, teachers can do this alongside principals – so long as there’s buy-in from principals. Some school leaders may choose to look at ceding control to teachers as a way of helping them, though others might say they’re just subverting authority.

“You’re a great leader if you’re not threatened by the concept,” Bakken said.

And with those supportive principals, educators can have autonomy over their classrooms, even about such issues as having input into assessments being used.

WHY THIS IS IMPORTANT

Having teachers feel and be empowered as school leaders has many benefits, according to Barnett Berry, founder of Center for Teaching Quality. High among them is establishing trust among students, parents, and teachers.

"No one knows better what students need than the teachers," Berry said. For this reason alone, schools must make it a priority to allow teachers to make important decisions that will directly affect their students.

Berry cites examples of schools in Singapore and Finland that create the space for teachers to develop leadership skills and take more control over school policies. "They have the time to both teach and lead," he said.

But there are big barriers to overcome in making this model the norm, he added. Too many schools have organizational schedules that force teachers to be isolated from each other. There's a lasting belief that teachers are all the same and must play the same roles. Highly successful teachers may surface "inconvenient truths for reform." And the accountability systems in place discourage both teachers and administrators from taking risks.

"Leadership is all about risk taking," Berry said.

When it comes to teacher evaluations, the staff “police each other,” Bakken says. Plus, they hire coaches to observe them, and work with a personnel committee on those specific issues that come up. “We get a lot of feedback from each other,” she said.

When it comes to teacher evaluations, the staff “police each other,” Bakken says. Plus, they hire coaches to observe them, and work with a personnel committee on those specific issues that come up. “We get a lot of feedback from each other,” she said.