The English language learner population in the United States is growing quickly, posing a challenge for cash-strapped schools struggling to balance the diverse needs of learners. And while technology is becoming a more ubiquitous part of the school experience, it hasn’t always been used effectively to improve the language skills of English learners. A new curriculum using both online modules and teacher-led instruction developed by Middlebury Interactive Languages in partnership with Hartford Public Schools is showing promise as an engaging way for students working on their English skills to also access challenging content.

Middlebury Interactive Languages is known for its online world languages program, but the partnership with Hartford marks the company’s entry into developing a blended-learning program meant for students learning English. Middlebury used research showing that English language learners need to develop academic English to succeed in school, as well as motivation to learn a new language through challenging and interesting work. To that end, the ESL curriculum uses content from science, math, social studies and English language arts curriculum as the basis for building up language skills.

“The whole process and developing these courses has been extremely collaborative with the real users,” said Aline Germain-Rutherford, chief academic officer for Middlebury Interactive Languages. “We take [the teacher and student] feedback and integrate that into our design.” For example, the Middlebury designers had little understanding of how much language a level one ELL student has. After looking at an initial prototype, Hartford educators came back to the company explaining areas that needed more background, context and clues to scaffold a student's understanding of texts.

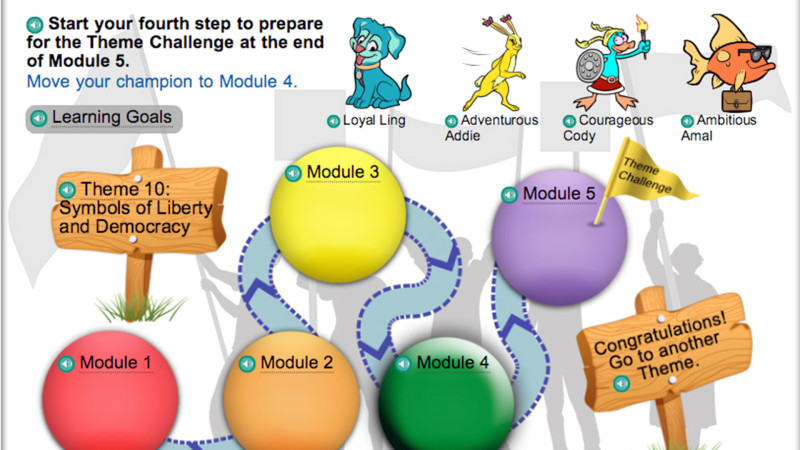

Hartford educators have been pleased with the progress their 4th-8th grade students are making using the blended learning curriculum and with the collaboration generally. They are currently piloting the program in the eight schools with the highest population of English language learners. “The curriculum is not static,” said Mary-Beth Russo, a Hartford ELL coach about the program's flexibility. “It’s online, but you can take parts of it and build out, and it’s theme based.”

Before, Hartford used a typical model that included both helping English learners within their subject area classes and pulling them out to work on language specifically. If a class was reading The House on Mango Street, the ELL teacher might try to front-load important vocabulary with students so they would have some idea of what was going on in the book, but often limited language skills still kept those students from participating in discussions.