“It’s certainly possible that some dyslexics have special abilities in areas not related to reading, just as other kids could have special abilities in one or two areas but struggle in other areas," said research scientist and speech-language pathologist Peggy McCardle, former branch chief at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), U.S. National Institutes of Health. "We know that there are gifted children in the world, and that some of them are dyslexic. What we don’t know — and to date there is no real evidence of this — is whether the dyslexia and the giftedness or talent are connected, or just happened to co-occur in that person. People are looking at ways to study that, with good research designs and solid methods, but so far it has not been done."

McCardle goes on to call the dyslexia-talent connection “a popular idea,” and admits it’s hard to say to wait for solid evidence. “But if we are to consider redefining a diagnosis, or changing a practice, we must be careful to be sure we’re right. If your dyslexic child has some special abilities, that’s wonderful, and that means that there are areas where he or she can be successful, which could make him or her feel less discouraged about school and learning. But it’s also important to keep in mind that environment, advantages and opportunities can nurture talents or abilities."

In poorer schools and families, dyslexic children may often have fewer opportunities to find and hone special abilities, making it even harder to tease out the connection.

Brock and Fernette Eide, a general practitioner and a neurologist who are also husband and wife, are quite interested in connecting dyslexics to their abilities, focusing on what dyslexics can do instead of what they can’t. Soon after they opened a Seattle clinic for students with learning differences in the late '90s, they began to notice a pattern in dyslexic students and their families.

“It became apparent that [in dyslexia] we were seeing kids with different patterns of optimization and specialization in cognitive function,” Dr. Brock Eide said. “When you start looking at those optimizations, you realize that building certain skills in certain areas usually entails a trade-off in function in some other cognitive set. So, what we were seeing with these kids is that they were optimized in ways that gave them difficulty in certain areas of function — which is why they ended up in our office. But when we looked closely, we were also seeing that those difficulties usually represented the flip side of other talent sets.”

Those talents, report the Eides, might be anything from high levels of spatial reasoning and creativity to outstanding social skills. The Eides said that time and again, families of dyslexic students would compare their child to a relative who had similar issues. For instance, a father might say, "Yes, my son is just like his grandfather, who struggled in school, but then went on to become a successful geophysicist." The Eides became “fascinated” with the pattern, which led them to begin their own search for research to support their data.

Their book, "The Dyslexic Advantage," outlines the talents of dyslexics that may be due to different brain structure. As far as the research to support the correlation between dyslexia and talent, the Eides said there are currently about 25 papers from around the world addressing the topic, and numerous universities, many in Europe, continuing to explore the connection between dyslexia and certain talents and abilities. While most are small samples, and are published in some obscure journals, the Eides say what mattered more to them than the quality of the studies, standing alone, was the recurrent evidence found around the world of people who struggled with reading and writing simultaneously -- excelling in areas like engineering, arts and design, and entrepreneurship.

Following their passion for the “upside” of dyslexia, the Eides were prompted to start a nonprofit, also called The Dyslexic Advantage, to promote the positive identities and achievements of dyslexics, which now boasts 15,000 registered members. They have set up connections with professional organizations and universities to identify groups with high incidence of dyslexia. They recently participated in a “neurodiversity in the workplace” conference at Microsoft, where they heard compelling stories of successful dyslexics in the tech force, and how they often compensated for their weaknesses by teaming up with those who had complementary strengths. And they are preparing to release a survey of more than 2,600 participants, called Dyslexia at School, in which those surveyed, mostly parents, give insights into how schools are handling dyslexia in the classroom, and ways in which schools can help support students with learning differences.

According to the Eides, the real world is often a welcome and wonderful change from school for the learning disabled, because suddenly their skills and talents have an arena to flower. Typically dyslexic strengths, like incidental and experiential learning and big-picture thinking, don’t have as many applications at school, unless schools purposely create classes that can harness both. In their clinical work, the Eides often found students living with dyslexia who had been “so broken down and conditioned to think of themselves as being defective, that by the time the development and environment becomes more conducive to their success, they have lost believe in their ability to make something of themselves.”

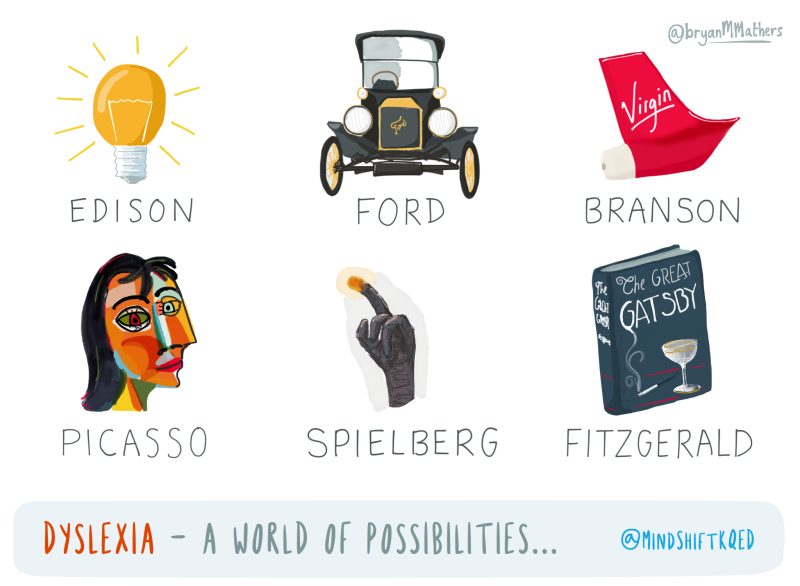

The researchers and clinicians at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center Reading Clinic are more measured about promoting the upside of dyslexia — not because the upside can’t be real, but because the struggles to get through school for children with a learning disability are real. Dr. Sheryl Rimrodt, who runs the pediatric clinic, said, “Not every single kid with dyslexia is gifted. When these kids leave my clinic, my goal is to help them feel positive that they will go out and get what they need,” she said. “I will say things like, 'You have a dyslexic brain, like Walt Disney had a dyslexic brain. You are a smart kid.' ”

Rimrodt also cautions saying too much about special talents that don’t seem academic in nature. “I don’t want kids to sell themselves short about going to college. So I will make sure that they know there are plenty of good people out there who have done plenty —academic work, who are in medical school, law school,” she said. “I want to give them the broad picture. I want them to understand that there’s a world of possibilities.”

Brock Eide recalled a recent phone call he received from an award-winning pediatric surgeon, a pioneer of many kinds of life-saving surgical procedures. The surgeon had called because he wanted to attend a local conference for dyslexics. However, he was having trouble filling out the registration form.

“This doctor can walk you through the experience of all the surgeries he performed over the years,” Eide said. “His memory is optimized for a different set of functions. And for all those kids who survived because he was their surgeon, thank goodness that he can’t remember his phone number, or his Zip code! He uses his mind for something better.”

A recent popular Twitter hashtag called #SayDyslexia has spread one particularly useful idea: In order to be recognized as a gift or a curse or perhaps somewhere in between, dyslexia first must be recognized at all. According to the Eide’s Dyslexia in School survey, 86 percent of those surveyed received diagnoses from an outside source other than school, although school is where reading problems almost always begin.

Through all the stories reported here, one thing remains consistent: While many children and families feel the often debilitating and humiliating effects of not understanding why they can’t read and write like everyone else, there is a lack of understanding about what dyslexia is and is not; how to identify dyslexic students and intervene early; and how to structure classrooms to accommodate an astonishing range of neurodiverse strengths and weaknesses.

This misunderstanding is happening at the state and local level, in homes and in schools and in classrooms. It’s happening when children in the lowest reading group are told that it will all come together if they would just apply themselves. It’s happening when teachers unwittingly give prizes for reading contests based on number of pages read. It’s happening when states administer conflicting and confusing guidelines that leave families and schools struggling to put a name to the problem. For many kids with reading problems, the name is dyslexia.

Experts agree that the earlier the diagnosis and intervention, the brighter the future for all those with dyslexia. For some, reading may never come easy. Dr. Brooke Soden, associate director at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center Reading Clinic, said the reading person is only a piece of the whole person.