Most high school teachers are familiar with students who obsess over every missed point on an assignment. It’s annoying; and many teachers wish students were more focused on the process of learning and their own growth, instead of the final grade. But putting the process front and center can feel difficult in a results-oriented school. While most teachers can’t entirely move away from grades, they can use simple strategies that require students to reflect on their progress, evaluate their work and set goals for improvement.

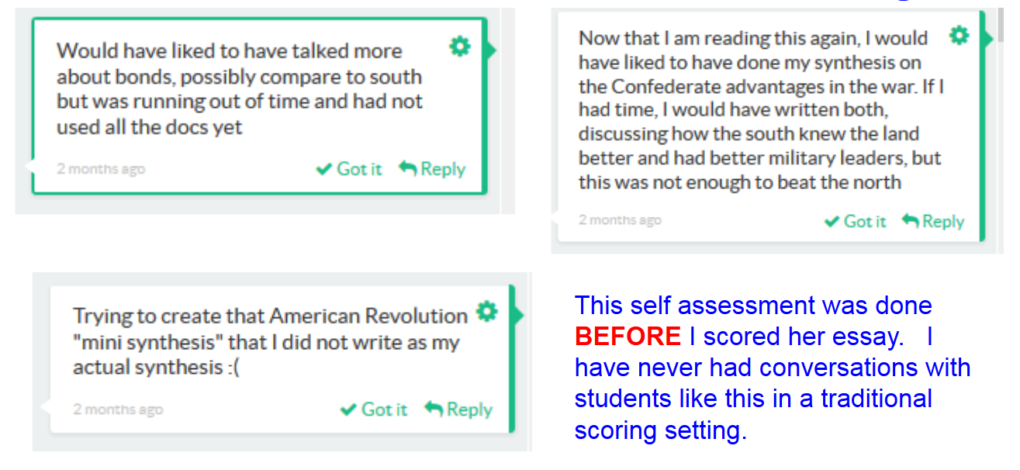

Helping students learn to evaluate their own work is a crucial skill that taps into their metacognitive abilities. Franklin High School teacher John Leighton has come to see self-assessment as a crucial skill for his history students, one that he intentionally cultivates with three simple strategies.

“If the kids know what they’re working towards, and they know where they stand on the route to get there, they are more likely to get there,” Leighton said at the Building Learning Communities conference held in Boston. He has found that the students who are reflective about their work are generally his best students, so he tries to cultivate that reflex in all students.

VIRTUAL STUDENT-LED PARENT CONFERENCES

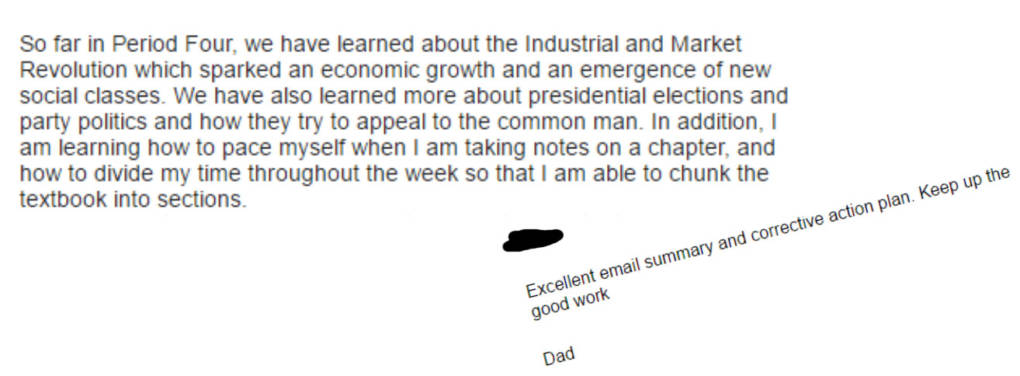

Parents often make it into school only once or twice a year, if that, but communication about what’s going on in class doesn’t have to stop there. Leighton has his students email their parents monthly, including him on the emails as well. In each missive the student must give an update on how they are doing in the class, review the content and skills they are learning at that time, and set a goal for the next month. They also have to reflect on how well they met last month’s goal.

“I want parents to see the class through the kids eyes,” Leighton said. He urges students to use data in their emails home and to think of it as an opportunity to make an argument and support it with evidence. When kids set goals, he guides them by asking that the goals be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-based. “I was very surprised at how detailed the kids were,” Leighton said.

These monthly emails not only serve to keep parents apprised of what’s going on in the classroom, but also give parents a chance to write back, acknowledging their child’s hard work and thoughtfulness. Or, if a student isn’t doing well, these emails can open the door to difficult conversations. “It has filtered out a lot of those surprise emails by parents,” Leighton said.