“Context and prior knowledge are critical components in fostering comprehension, regardless of the topic,” according to Faith Wallace, co-author of Teaching Math Through Reading. Reading literature is one of several ways to build that context and background knowledge. “When math is integral to the story students can learn the concepts in a natural way, become inquisitive, engage in thoughtful conversation, and more,” said Wallace.

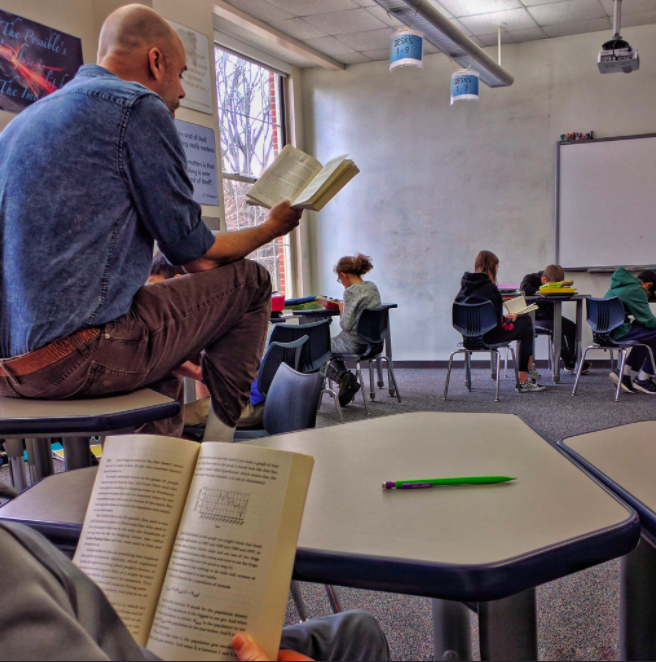

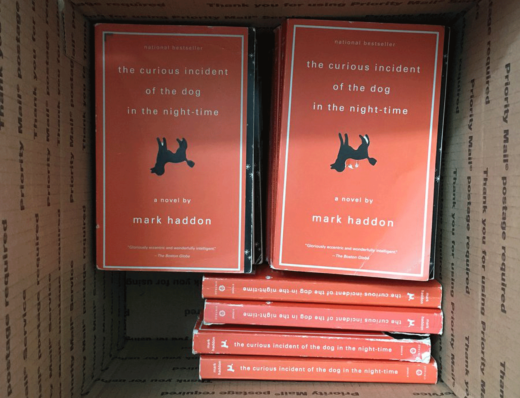

The combination of mathematical, literary and personal reflection, along with students’ genuine interest in the story, leads to higher student engagement, Bezaire said. Year after year, his students who previously kept quiet raised their hands during discussions of The Curious Incident. “Very often, this continues into the rest of the year after our novel study is done,” he said. “Often when middle school students get momentum in a certain class, they are hardy enough to allow it to continue even when the unit of study changes.”

Calculus Book Club

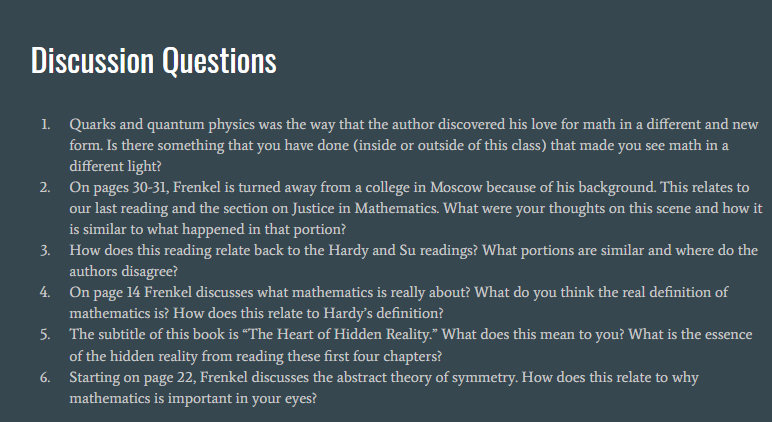

Two years ago, when a schedule change created extra periods in Sam Shah’s multivariable calculus course, he instituted a class book club. The students started with the satirical science fiction novel Flatland by Edwin Abbott and later read several nonfiction texts about mathematicians and mathematical ideas. Book club meetings took place during a block of 30 to 40 minutes a few times per month, with a rotating pair of students leading each discussion.

In the first year, Shah said, his biggest challenge was deciding how much to chime into the discussions. It’s as important to create a relaxed atmosphere for the meetings as it is to keep students focused on the text, he said.

During the second year of book club, he made an effort to intervene less often. “When I reflected upon what my goal was ... it wasn't to teach kids how to do close readings and feel like drudgery. The readings were picked to inspire kids to think, to have strong feelings about, to be curious about something mathematical that showed up, to see and think about math differently.”

During the second year of book club, he made an effort to intervene less often. “When I reflected upon what my goal was ... it wasn't to teach kids how to do close readings and feel like drudgery. The readings were picked to inspire kids to think, to have strong feelings about, to be curious about something mathematical that showed up, to see and think about math differently.”

That’s what the readings did.

“What I appreciated most is how humanizing our conversations were of mathematics — in terms of who was doing it — and how much curiosity students brought to the mathematical ideas they were exposed to.”

One student, for example, used The Calculus of Friendship by Steven Strogatz as the model for her final course project, in which she explored her identity and mathematical experiences using calculus concepts.

Although another schedule change this year forced Shah to drop book club from calculus, he has continued the club outside class with interested students.

“If you have the time, it's a magical way to get kids to see mathematics through a number of different lenses,” he said.

Shah created a list of titles that would work well in a math book club, and Bezaire’s curriculum for The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is available on his website. MindShift asked the two teachers to share their advice for educators who want to try incorporating literature into their own math classrooms.

Tips for Curious Incident

- Lay the groundwork for the unit by communicating with parents, other teachers, administrators, students before diving in. There may be resistance: the book has been removed from some schools because of profanity.

- Stock up on throat lozenges or tea with honey. “I speak out loud in front of classes for a living, and it's still a stretch for me to read the book out loud four times per day,” Bezaire said.

- Pre-read each day's reading passage to find teachable moments: clues, red herrings and math worth expanding on. Make notes in your copy of the novel to make things easier the second year.

After class students complete written reflections about the book, with different types of questions serving multiple pedagogical goals.

After class students complete written reflections about the book, with different types of questions serving multiple pedagogical goals. During the second year of book club, he made an effort to intervene less often. “When I reflected upon what my goal was ... it wasn't to teach kids how to do close readings and feel like drudgery. The readings were picked to inspire kids to think, to have strong feelings about, to be curious about something mathematical that showed up, to see and think about math differently.”

During the second year of book club, he made an effort to intervene less often. “When I reflected upon what my goal was ... it wasn't to teach kids how to do close readings and feel like drudgery. The readings were picked to inspire kids to think, to have strong feelings about, to be curious about something mathematical that showed up, to see and think about math differently.”