When most of the nation’s schools closed in March due to COVID-19, educators turned to whatever methods they could to keep learning going — from online classes to phone calls to drive-by packet pick-ups. Still, many students were unreachable, and as teachers navigated those challenges, they turned up the volume on discussion about educational inequities.

Much of focus has been on computer and internet access, but there’s more to equity than technology, according to Tricia Ebarvia, a high school English teacher in Pennsylvania. “We have to think about the ways in which we are recreating the systems and structures that have resulted in racial inequities in in-person education, but now in an online environment. And actually exacerbating them,” Ebarvia said.

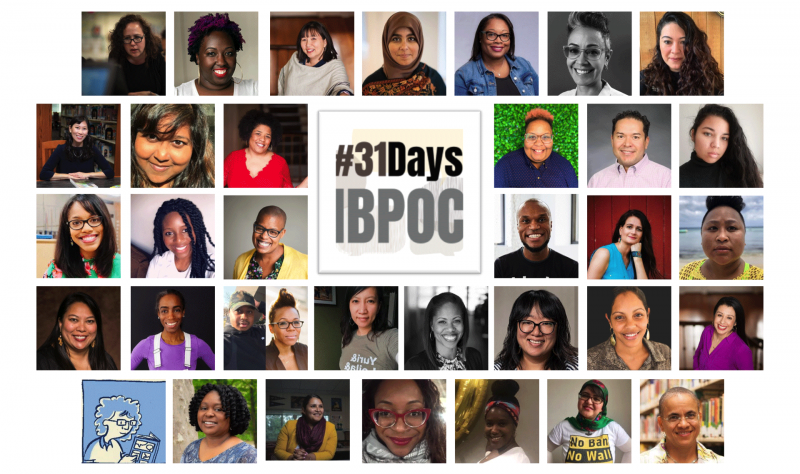

Ebarvia and Massachusetts-based literacy organizer Kimberly N. Parker are the cofounders of #31DaysIBPOC, a blog series that spotlighted the voices of Indigenous, Black and people of color educators throughout May. Now in its second year, the project, Ebarvia said, serves as “a beacon and a flashing light to people, to educators, who are willing to listen, to say, ‘You know what? Maybe there’s a different way to go about this. Maybe there’s wisdom in the experiences of IBPOC communities that we can learn from.’”

That kind of wisdom could be useful to government and school leaders as they figure out what the fall semester will look like. While more than 50 percent of public school students are of color, about 80 percent of public school teachers are white. In many of the #31DaysIBPOC posts, the contributors point to ways that the education system has harmed both IBPOC students and teachers by devaluing them, demanding assimilation to white values and centering only white voices in professional development.

The authors also do more than provide examples of everyday, structural racism. They rejoice in being the teachers they needed as children. They draw strength from IBPOC educators and activists of the past. They envision working together for a better future.