“Um, I have new shoes.”

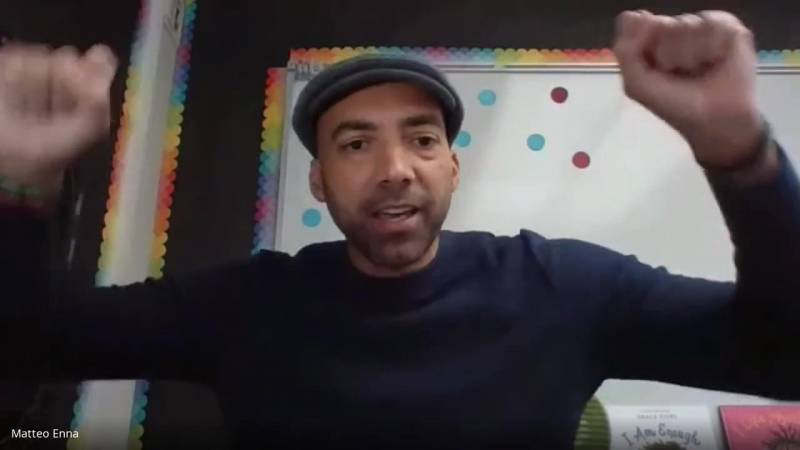

“What?” asked the teacher, a smile tugging at the corners of his mouth.

“I really have new shoes.”

Maily’s head bobbed out of view like a duck diving for insects. Her voice dipped, too, as she narrated from below. “I’ve been wearing them for the whole class, and they’re really pretty.”

Bobbing back up, Maily held the shoes aloft in all their pink-laces-and-velcro-strapped glory.

“WOW! Beautifuuuul!” exclaimed Gianna, pressing her face toward her screen. Syncopated admiration rang out as other classmates unmuted themselves to chime in.

“Next time I go to class without COVID, you’re gonna see me wear them,” said Maily.

“Oh, deal,” said Mr. Enna. “Post-COVID, K?”

At the time, neither Maily nor her peers had ever set foot inside Mr. Enna’s classroom. Like thousands of other young learners, they were part of an unplanned pandemic experiment: kindergarten in the cloud.

At the start of the year, the prospect of this unusual entrée into elementary education prompted much anxiety among parents and teachers nationwide. But while the long-term effects of pandemic learning remain to be seen, Mr. Enna and several parents have been pleasantly surprised at how well virtual kindergarten has gone.

Melissa Eichenberger said her daughter, Gianna Servedio, has thrived. The six-year-old is reading on grade level, can count by tens and generally loves to learn. “It's just been crazy how much she’s getting out of it for looking at a computer screen,” Eichenberger said.

Not that it’s all been smooth sailing. Among the challenges, parents described Google Meet glitches, kids getting distracted by toys and limited social interactions with peers. But Tayo Enna, who has taught kindergarten for 16 years, said he approached distance learning with a maker mindset. “I looked at this Google Meet as, here's my tool. How can I make this work? How can I make this fun for the kids?” he said. “Because if I could motivate kids and keep them engaged, then I can teach them the content, teach them the curriculum and they'll learn.”

Whether online or in-person, that mindset is fundamental, according to Jennifer LoCasale-Crouch, an education researcher at University of Virginia. Beliefs are one of three key elements she studies related to how adults support young children’s academic and social development.

The second key element? The skills to enact supportive beliefs, including: observing what children think and do, planning based on those observations and reflecting on what worked and what didn’t. It takes adjustment, but LoCasale-Crouch said that applying those skills to a virtual setting is pretty straightforward. The bigger challenge, however, might be in adapting the third key element of supportive teaching: responsive behaviors.

“Being responsive in person may mean you’re getting closer to a child,” she said. “You might get down to their level so they can see and feel you. That's harder obviously to do virtually, but you're still able to do things like call somebody's name, give them a little smile, a little joke.”

Humor and levity played a big role in Mr. Enna’s virtual classroom this year. He often held staring contests with kids, poked fun at himself or gave facetious advice.

“Make sure no one cuts their hair. That’s how I’m bald. I messed up on an art activity once,” he quipped one morning as his students cut out paper snowmen. “Just kidding, Emily. It really didn’t happen that way.”

Kidding or not, Mr. Enna called out students’ names frequently throughout each lesson — praising effort, reengaging distracted pupils and asking questions to lock in learning.

“Oh, Calypso, looks like you’re doing a nice job cutting.”

“Kien, where are your flapping wings?”

“How many bears do you have in all now, Gabriel? Can you count that in Spanish, too?”

Those techniques, as well as the jokes, were built on something basic: getting to know the kids he saw on screen every day. Enna said he usually learns about his students during recess conversations and small interactions throughout the day. This year, with fewer one-on-one opportunities, he took a new tack. Instead of jumping into instructional content immediately, he devoted the first and last few minutes of every virtual class to non-academic conversations on topics such as favorite foods, movies or weekend plans.

“Every kid wants to share that, even if it’s a small thing,” he said.

So when Maily showed off her new shoes at the end of a lesson in February, it wasn’t an accident. Early in the year, kids would unmute themselves to share such things in the middle of a lesson, Mr. Enna said. But as they grew accustomed to the routine, he no longer had to monitor microphones as closely.

The entire class met for two 45-minute sessions four mornings per week. Mr. Enna held small group reading lessons in the afternoons on a rotation. Wednesdays were mostly asynchronous activities. With less instructional time than a regular year, Enna acknowledged some subjects got shortchanged. Students only had one live writing exercise per day, instead of two or three, for example. Still, he felt that if he tried to cram everything in rather than devoting time to relationships, he’d lose the true engagement needed for learning.

LoCasale-Crouch affirmed that instinct. “In a crisis, the first thing we need to do is connect,” she said.

Fatime Brown said that Mr. Enna’s curiosity about his students made an impact on her son, Jace Duncan. Before kindergarten, Jace was selective about who he spoke with, Brown said. Not so in Mr. Enna’s virtual classroom. The teacher quickly picked up on Jace’s love of math and science. He shared Neil deGrasse Tyson videos with Jace and quizzed the six-year-old on geography.

“Jace, do you want to share your knowledge of the world right now?” Mr. Enna asked at the end of one class.

“Yeah! Yeah! Yeah yeah yeah.”

“OK, tell us something about Denmark.”

“Greenland is an autonomous territory of the country of Denmark,” Jace said from his kitchen table. In the background, his mom put away breakfast dishes.

The ability for the whole class to witness these kinds of exchanges could be a positive effect of virtual learning, according to LoCasale-Crouch. In person, such conversations might happen individually. Online, “students might be getting more examples of relationships and supports by seeing it and hearing it that they wouldn't necessarily have in the classroom itself.”

Whether talking about gains or losses, it’s too soon to know the long-term effects of the pandemic on early learning, LoCasale-Crouch said. Outcomes depend greatly on the school and family context. Kindergarten enrollment was down nationally this year, and families opted for a wide mix of alternatives. Teachers, too, were working under differing degrees of support or stress.

For several parents of Mr. Enna’s students, the main gap they saw in their children’s virtual kindergarten experience was the inability to interact in the same space with peers. They were glad for a chance to test the water in the final weeks of school. Late this spring, as Santa Clara County’s coronavirus case rate and positivity rate fell, families at STEAM@Stipe School, were given the option to send their children to school two days per week.

Back in February, a few minutes after Maily first displayed her sparkly Skechers to the class, she showed them off again. This time they were on her feet. Pointing her camera downward, Maily repeated her promise that her classmates and teacher would see them in-person eventually. “If you see me literally wearing (them), you're going to be amazed,” she said.

“That will be quite the day,” said Mr. Enna.