If a child goes to the doctor because they have a tummy ache and they throw up on their doctor, the doctor doesn’t say, “This kid needs discipline!” The doctor asks questions. “What did they eat? Do they have a fever? They get curious about what’s toxic in that child’s system so that they can most appropriately treat it,” said Dr. Shawn Ginwright, founder of Flourish Agenda and professor of education at San Francisco State University. The same goes for when children who have experienced trauma act out. “They emotionally throw up on teachers,” he said. “That means schools need to have a wider array of tools.”

Social-emotional learning practices are just some of the tools making their way into more classrooms to help students manage trauma and relationships during pandemic schooling. Even so, the general understanding of trauma – and therefore the responses to trauma – is often limited. “While the term ‘trauma-informed care’ is important, it is incomplete,” wrote Ginwright. One of its shortcomings is that it leads people to think of trauma as only an individual experience instead of thinking about it in terms of systems or contexts. “We need to have a broader perspective of how the environment – where young people live and play – can be traumatizing,” said Ginwright. Another way many trauma-informed models fall short is that they are often deficit-based and focus on what is going wrong in a child’s life rather than looking at areas of possibility.

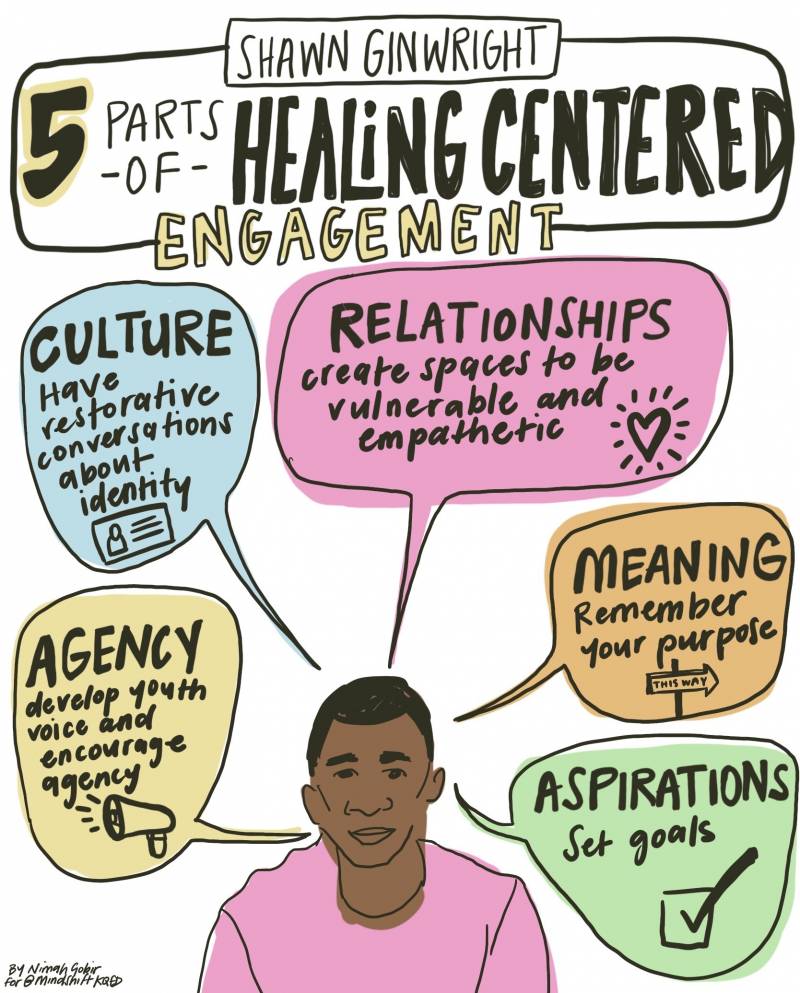

To respond to the broader conditions of trauma, Ginwright developed healing-centered engagement (HCE), a strength-based social-emotional learning strategy for educators and caregivers. A healing-centered approach to addressing trauma requires a shift from asking a person, “What happened to you?” and instead asks, “What’s right with you?” Based on Ginwright’s research with young people and families for over 30 years in the San Francisco Bay Area, the healing-centered engagement model builds on trauma-informed care by focusing on development across five key principles: culture, agency, relationships, meaning and aspirations.

Culture

Racism, classism and discrimination based on sexual orientation and immigration status can be stressors for young people and their families. “[Identity] is oftentimes the first area of harm that young people experience,” Ginwright said. However, healing-centered engagement focuses on culture and identity as pathways to healing. “We need to engage in restorative conversations about various types of identities that young people bring into our community programs or schools,” said Ginwright.

For example, many students of color are told that they need to work twice as hard as their white peers, which may lead to stress, shame and anxiety. Instead of reinforcing the idea that students of color can’t be their authentic selves, schools may find it helpful to explore self reflection as a healing practice. They can set aside time for students to answer questions like, “How has your connection to a community or identity helped you through a hard time?” or “What are some healing practices rooted in an identity or community you belong to?” Strengthening introspection not only fosters healing, but leads to better decision making abilities and healthier relationships, said Ginwright.

Agency

Focusing on agency, youth voice and specific actions develops students’ ability to respond to traumatic environments. “Research shows that when we engage in action or some form of improving a problem, we find that action in and of itself facilitates a sense of well-being,” said Ginwright. Whether it’s making meaningful changes in their neighborhood or school, agency cultivates a sense of purpose and collective engagement. “We can act and respond in productive and collective ways to improve the environment where we live, work and play,” said Ginwright. “It provides us with a sense of control over what may be perceived as an uncontrollable situation.”