Excerpted from “Teaching Math to English Learners” by Adrian Mendoza with Tina Beene. Published by Seidlitz Education, 2022.

Embracing academic conversations in the math classroom becomes routine when teachers intentionally prepare content-based linguistic supports to guide and scaffold language. These opportunities for language are important because verbalizing thinking helps students with sense- making, analysis, and reasoning. When students process and engage in sharing, they gain problem-solving perspectives and address misconceptions or incompleteness in their ideas more than if they worked independently (Webb et al., 2014).

Structured conversations in a math classroom are especially crucial when teaching English learners (ELs) or students who may feel frustrated or anxious when classmates’ responses to questions bypass the problem-solving process and skip to the solution. When the EL has a different, viable perspective, they might struggle to communicate. There is still a misconception that the first to respond is smarter than the rest, leaving slower students with a feeling of failure or a self-perception that math is not for them. On the contrary, some of the best responses come from students who think carefully about the process they used to formulate an answer, but students must be reminded of this. In fact, some of the best mathematicians are slow thinkers (Boaler, 2015).

Structured conversations in a math classroom are especially crucial when teaching English learners (ELs) or students who may feel frustrated or anxious when classmates’ responses to questions bypass the problem-solving process and skip to the solution. When the EL has a different, viable perspective, they might struggle to communicate. There is still a misconception that the first to respond is smarter than the rest, leaving slower students with a feeling of failure or a self-perception that math is not for them. On the contrary, some of the best responses come from students who think carefully about the process they used to formulate an answer, but students must be reminded of this. In fact, some of the best mathematicians are slow thinkers (Boaler, 2015).

When providing structured conversations in math classrooms, equity also comes into play. We ensure that every student can engage in learning experiences as we provide them with academic, cognitive, linguistic, and affective support. Academic conversations are an essential component, as they directly affect reading and writing. The more structured opportunities students have to talk and process mathematical ideas, the better readers and writers they will become.

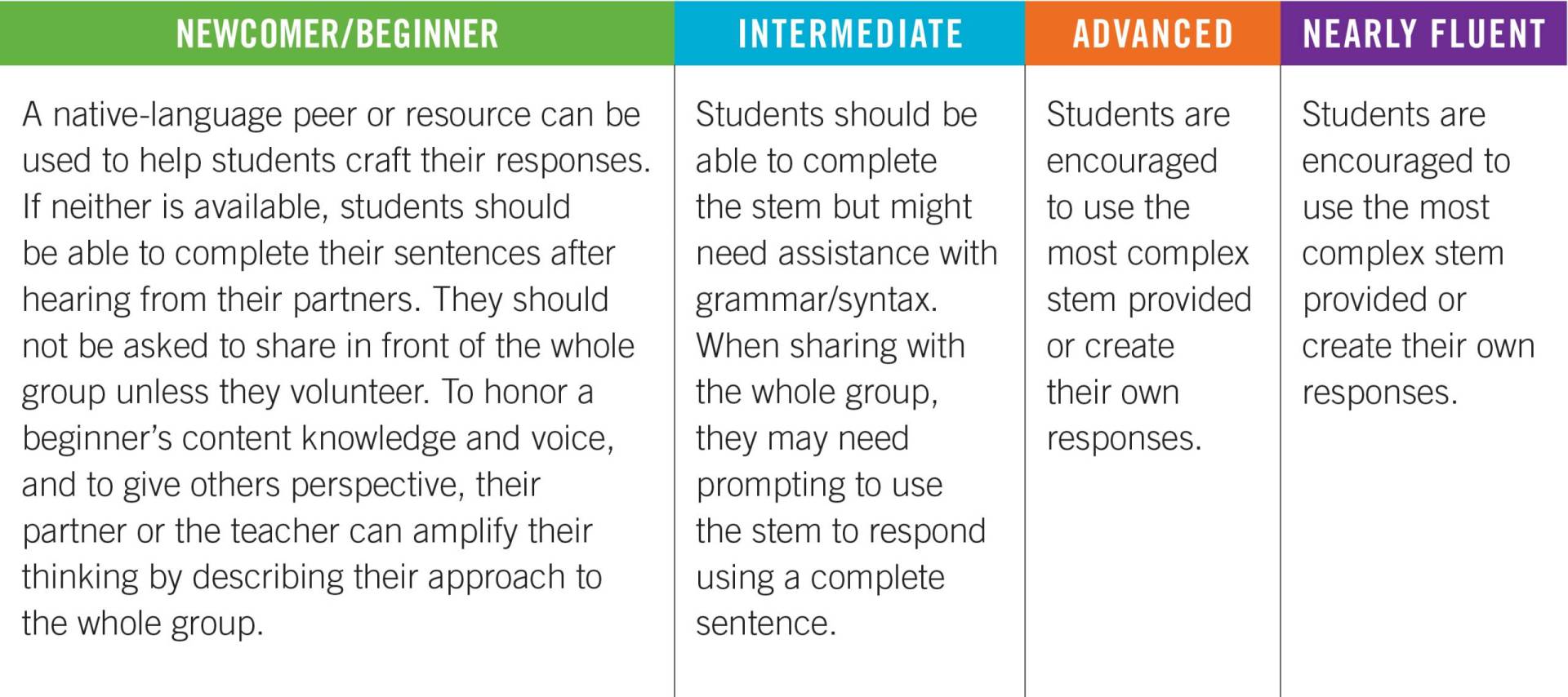

As a former instructional coach in a school district, one of my goals was to identify what I call “ghost students,” or students who almost never give answers even though teachers want them to speak. These students often go from class to class and never practice academic English, much less the language of mathematics. Once I knew who these “ghost students” were, I intentionally created support systems to ensure 100 percent participation. This support provided all students with language learning opportunities during math lessons and held them accountable. Some strategies that assist with total participation include the use of sentence stems, word banks, visuals, total response signals, and student randomization and rotation.

Conversations in Math

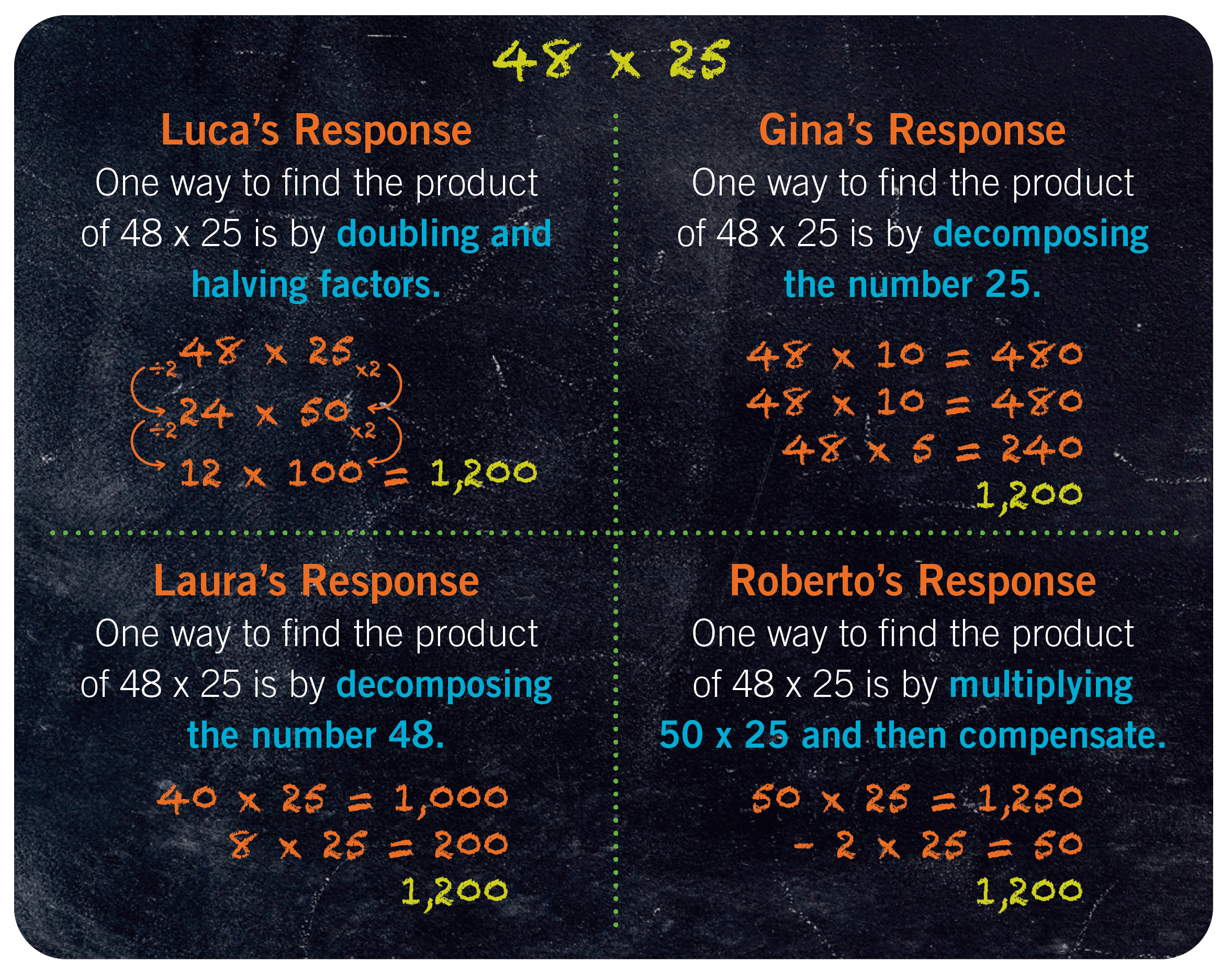

Conversations in Math is a routine designed to provide opportunities for students to share their mathematical ideas, much like Parrish’s Number Talks (2014). The difference is that the structure has a language focus, and students gain access to language by discussing their strategies for solving a problem and explaining the reasoning behind their work.

Adrian Mendoza

Adrian Mendoza Tina Beene is a consultant with Seidlitz Education. She is the author of

Tina Beene is a consultant with Seidlitz Education. She is the author of