“The percentage of students who are getting discounts, grants or scholarship aid from institutions has skyrocketed,” said Robert Massa, a retired college admissions and enrollment director who is now a research associate at the Center for Enrollment Research, Policy and Practice at the University of Southern California.

Colleges need to fill seats and maximize revenue. And a college can increase revenue when it discounts tuition because an enrolled student is still paying the remainder of a sticker price that keeps rising. From a college’s perspective, collecting reduced tuition from an enrolled student is better than collecting nothing from an empty seat.

Filling those seats is not a problem for the most selective institutions but those elite universities represent only a tiny portion of colleges. Many other schools struggle to reach their enrollment goals. That’s where the discounts come in. The less likely a student is to enroll in a college, the more discount the enrollment algorithm suggests to woo the student. “These are not-for-profit institutions, but like private businesses, they’re competing against each other on price,” Massa said. “If another college is giving $35,000 per student, I’m going to have to go there too to compete.”

Public universities have also been aggressively discounting since the 2008 recession, when states decreased public funding for higher education. To offset the shortfall, public universities looked to out-of-state students, who pay higher tuition. Tuition discounts help lure these students to attend.

Fewer students received tuition discounts at for-profit schools, down from 25% in 2015-16 to 21% of undergraduates in 2019-20. But the size of the average discount has grown from $2,750 to over $3,300 among students who got them. Far less discounting occurs at two-year community colleges, where posted tuition prices are much lower.

This institutional aid data comes from the 2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, which the Department of Education conducts every three to four years. More than 80,000 undergraduates and 2,000 colleges and universities were surveyed. In addition to a published report of tables, additional data was released on the National Center for Education Statistics’s DataLab website, and that is where I retrieved the institutional aid data for this story.

The numbers combine both need-based and merit aid granted by colleges and universities. No one is actually transferring funds to students to pay their tuition bills, but the aid does reduce a student’s bill from the published sticker price. The final cost – after discounts – is often referred to as net tuition price.

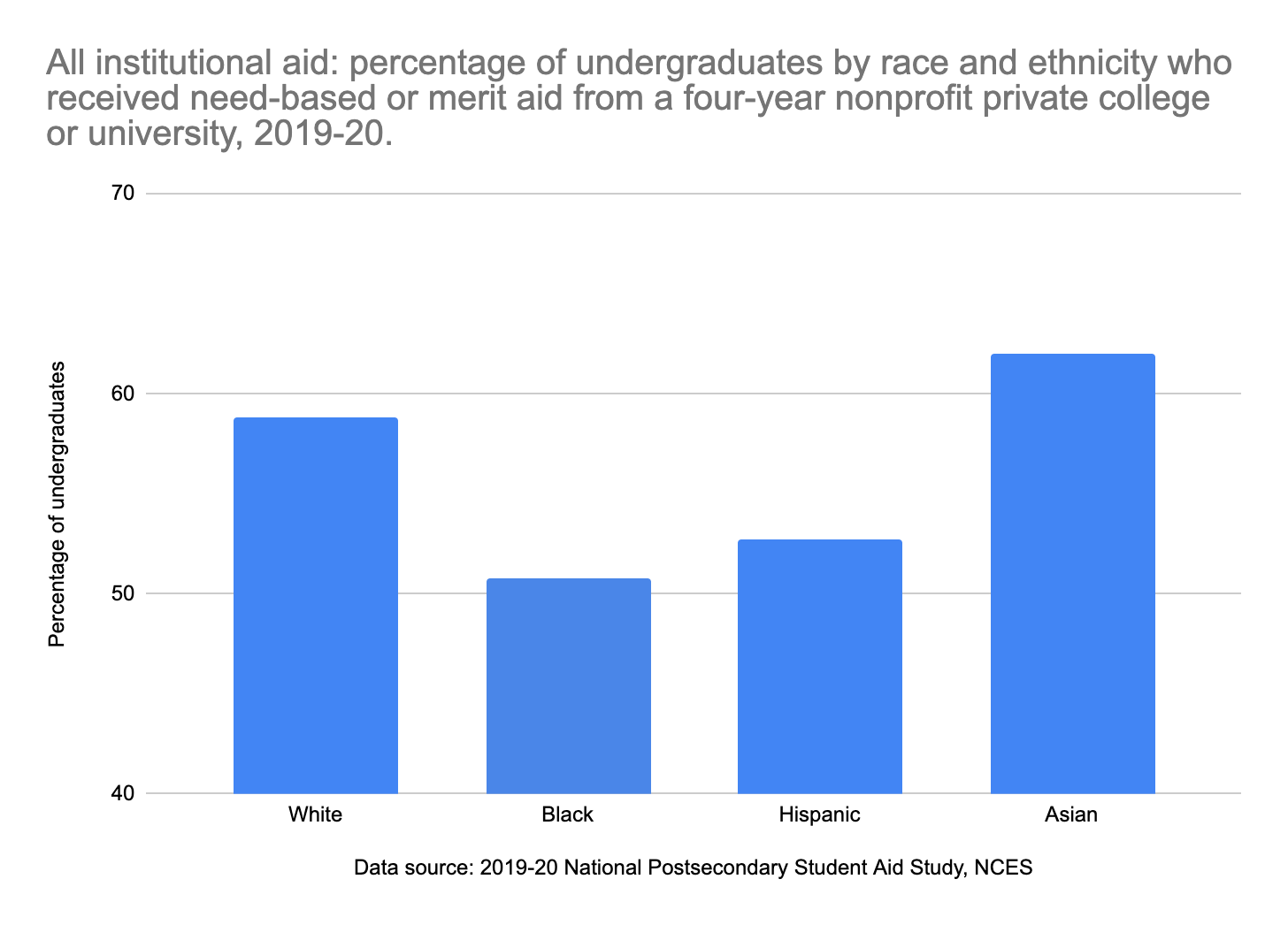

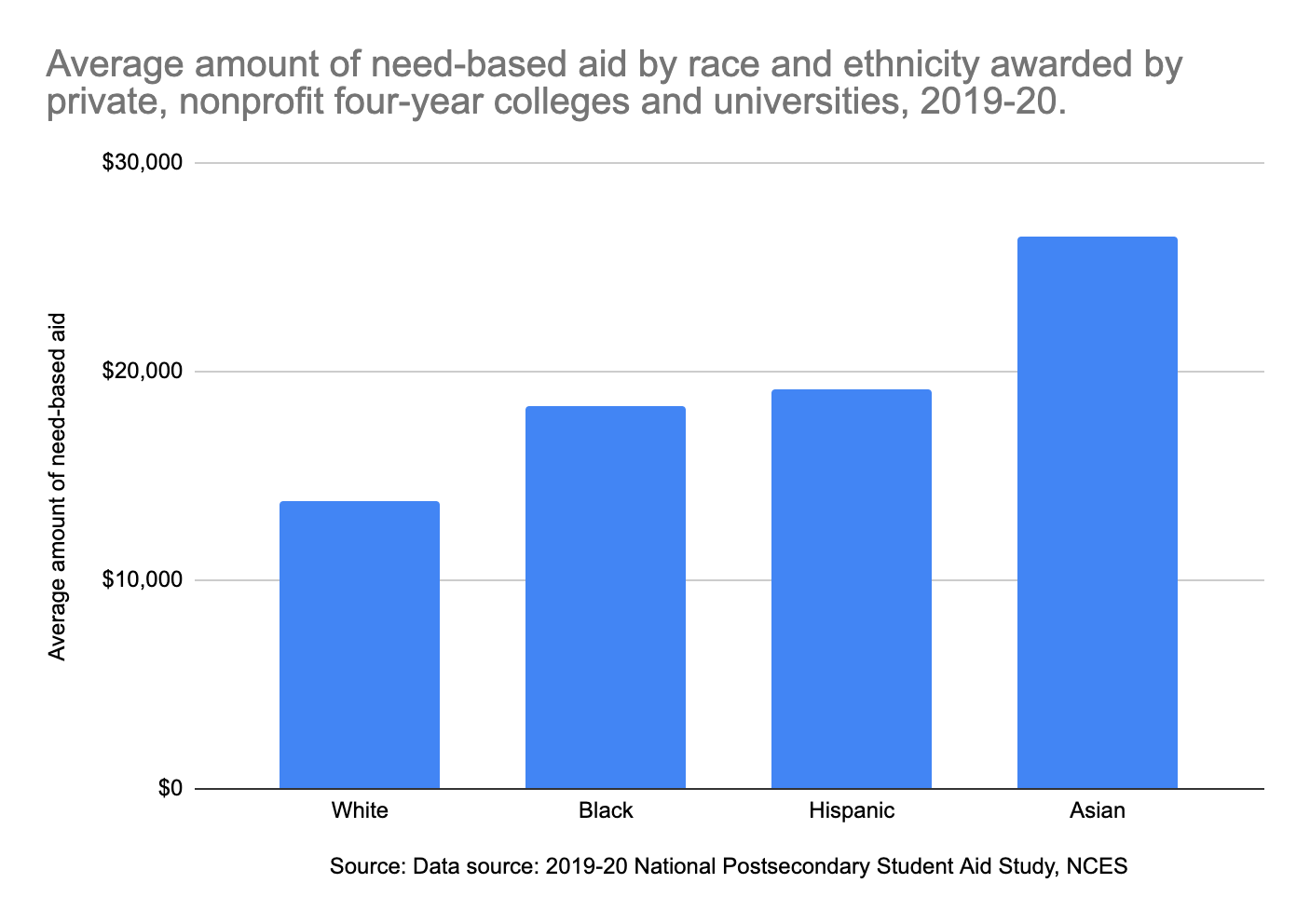

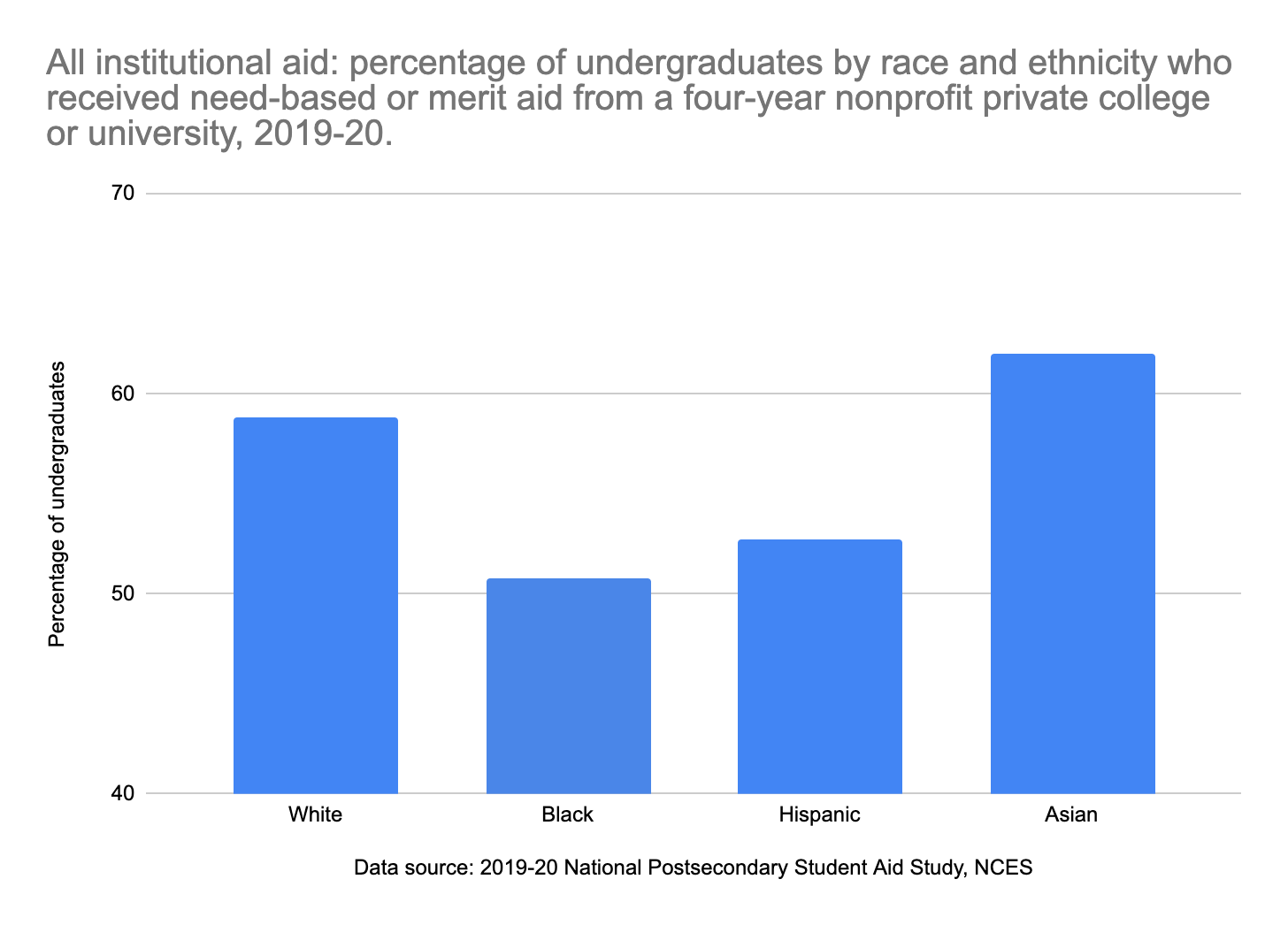

Asian and white students were more likely to receive tuition discounts or be awarded larger amounts. At private non-profit four-year institutions, 62% of Asian, 59% of white, 53% of Hispanic and 51% of Black students received institutional aid. For those who received these discounts, the average amounts were $26,500 for Asian students, $20,900 for Hispanic students, $20,700 for Black students and $19,700 for white students. At public four-year institutions, 39% of Asian, 35% of white, 31% of Black and 30% of Hispanic undergraduates received institutional aid. The average amounts were about $5,400 for white students, $5,200 for Asian students, $5,000 for Black students and $4,800 for Hispanic students.

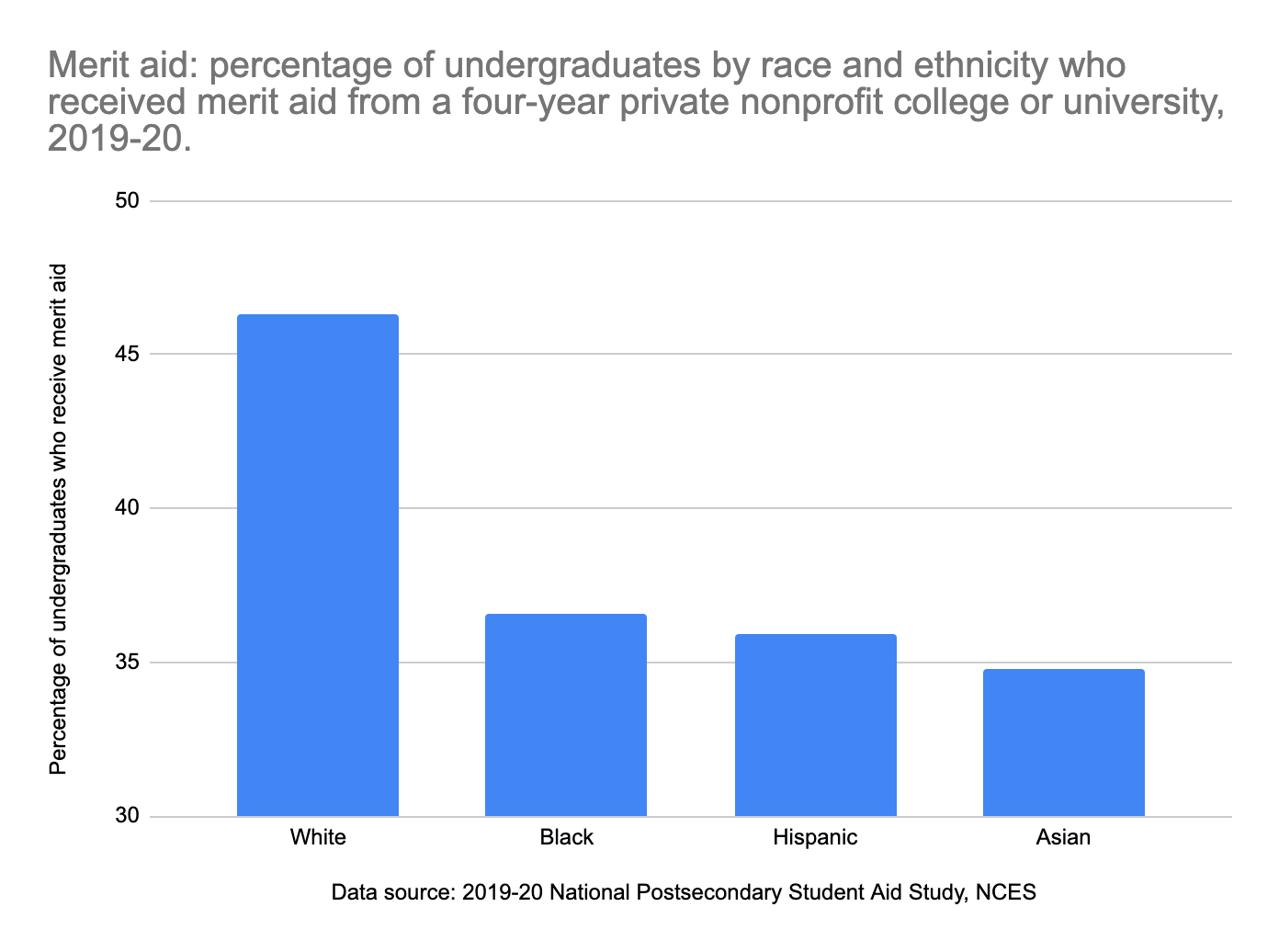

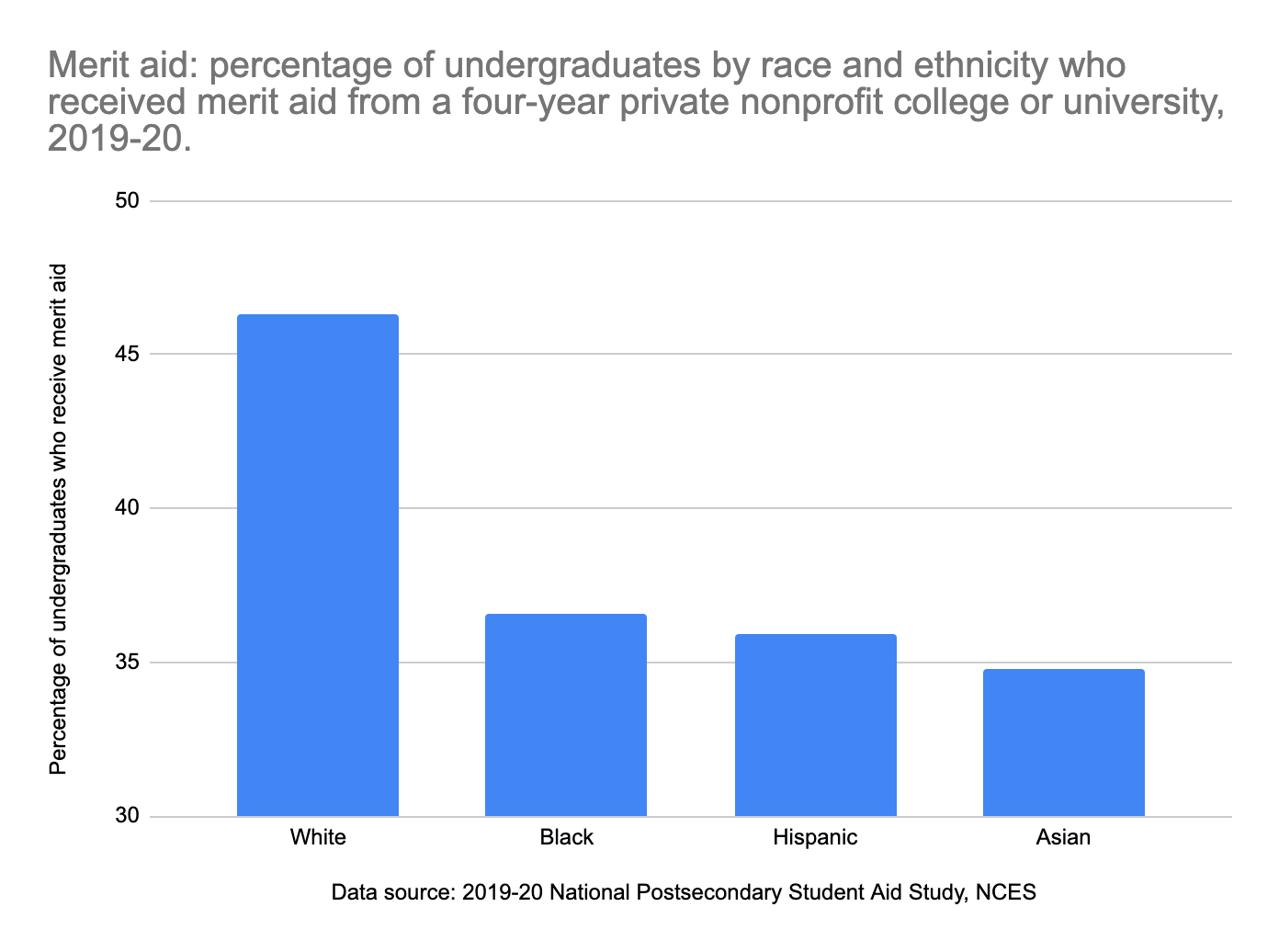

Looking at merit aid alone – subtracting out need-based aid – the sizes of the discounts rose sharply at private non-profit colleges, while the share of students getting them jumped at public colleges. “Put merit in quotation marks,” USC’s Massa said. “It’s really not about rewarding students for their wonderful performance in high school, as much as it is trying to change that student’s enrollment decision.”

Explaining why merit aid has been rising is easier than explaining why there are big racial and ethnic disparities. Massa’s hypothesis is that Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately lower income, while the algorithms target merit aid to students who aren’t needy but have the means to pay. From a business perspective, enrolling a low-income student is riskier because they are more likely to drop out of college, and then the college has to recruit a new student to replace his or her tuition revenue. A wealthier student is more likely to pay tuition for four to five years straight. Wooing students who are more likely to graduate also raises the possibility of more state funding for some public universities whose budget is partly based on student success metrics.

The algorithms also target prestige, Massa explained. White and Asian students have historically posted higher SAT and ACT scores, which has been an important component of U.S. News & World Report’s influential college rankings. High rankings attract future applicants, which bodes well for future enrollment and revenue.

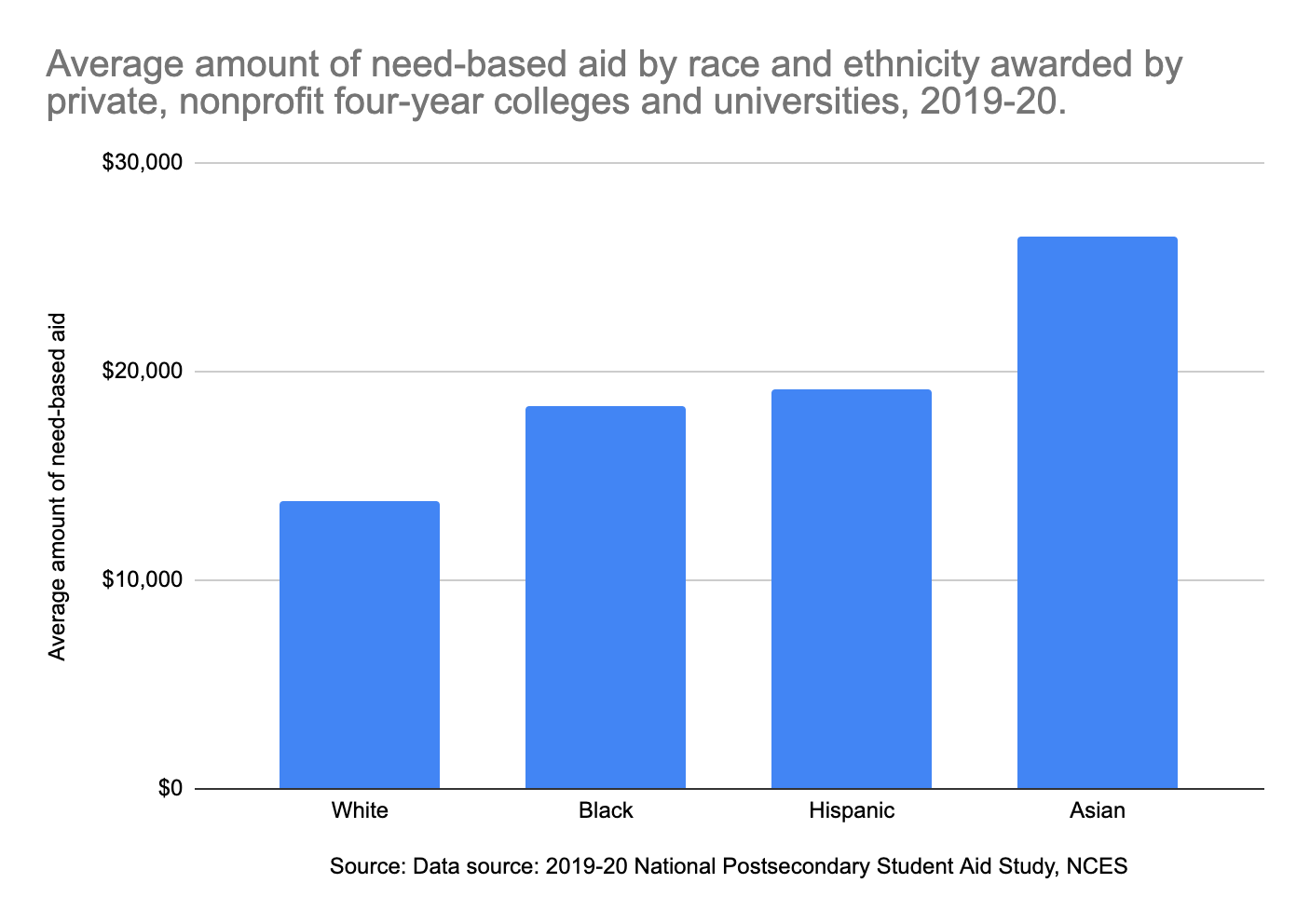

Need-based aid has increased, too. This is the aid that colleges give to students whose families cannot reasonably be expected to afford tuition, even after federal and state subsidies. At private colleges, 31% of students received tuition discounts because of financial need and the average discount was over $17,200, sharply up from $12,500 in 2015-16. Asian students were more likely to receive it and to receive larger amounts.

Jill Desjean, a senior policy analyst at the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, a Washington D.C.-based lobbying group, said need-based aid has climbed sharply because colleges keep hiking their sticker prices. “Say you get a $20,000 scholarship,” she said. “If the tuition goes up by $2,000 the next year, it’s not likely that the college is going to assume that the family can afford to spend $2,000 more. So they increase the scholarship to $22,000.”

Desjean couldn’t explain why there might be racial and ethnic differences in who gets need-based tuition discounts. Only a few dozen colleges are able to provide enough need-based aid so that students don’t have to take out loans. Clearly, colleges have a lot of discretion on which needy students they want to support and by how much.

There’s a widespread feeling that discounting has gotten out of control. But no single university can stop it without hemorrhaging students. And a collective compact to curtail discounts could run afoul of the Department of Justice’s antitrust rules, said Jerry Lucido, a professor of practice and executive director of the USC Center for Enrollment Research, Policy and Practice.

The end result, according to Lucido, is that giving discounts to students who could actually pay more often means a bigger debt burden for less wealthy students. The companies that create the sophisticated algorithms, he says, pitch “revenue enhancement” to colleges while the purported mission of educating students from all walks of life can seem like an afterthought.