In 2017, public interest lawyers sued California because they claimed that too many low-income Black and Hispanic children weren’t learning to read at school. Filed on behalf of families and teachers at three schools with pitiful reading test scores, the suit was an effort to establish a constitutional right to read. However, before the courts resolved that legal question, the litigants settled the case in 2020.

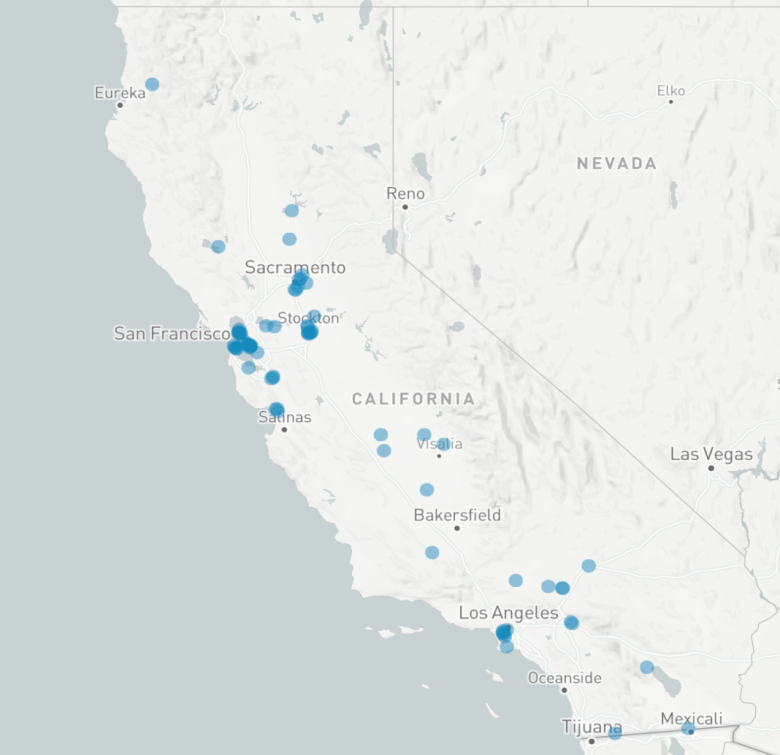

The settlement itself was noteworthy. The state agreed to give an extra $50 million to 75 elementary schools with the worst reading scores in the state to improve how they were teaching reading. Targeted at children who were just learning to read in kindergarten through third grade, the settlement amounted to a little more than $1,000 extra per student. Teachers were trained in evidence-based ways of teaching reading, including an emphasis on phonics and vocabulary. (A few of the 75 original schools didn’t participate or closed down.)

A pair of Stanford University education researchers studied whether the settlement made a difference, and their conclusion was that yes, it did. Third graders’ reading scores in 2022 and 2023 rose relative to their peers at comparable schools that weren’t eligible for the settlement payments. Researchers equated the gains to an extra 25% of a year of learning.

This right-to-read settlement took place during the pandemic when school closures led to learning losses; reading scores had declined sharply statewide and nationwide. However, test scores were strikingly stable at the schools that benefited from the settlement. More than 30% of the third graders at these lowest performing schools continued to reach Level 2 or higher on the California state reading tests, about the same as in 2019. Third grade reading scores slid at comparison schools between 2019 and 2022 and only began to recover in 2023. (Level 2 equates to slightly below grade-level proficiency with “standard nearly met” but is above the lowest Level 1 “standard not met.”) State testing of all students doesn’t begin until third grade and so there was no standard measure for younger kindergarten, first and second graders.

The settlement’s benefits can seem small. The majority of children in these schools still cannot read well. Even with the reading improvements, more than 65% of the students still scored at the lowest of the four levels on the state’s reading test. But their reading gains are meaningful in the context of a real-life classroom experience for more than 7,000 third graders over two years, not merely a laboratory experiment or a small pilot program. The researchers characterized the reading improvements as larger than those seen in 90% of large-scale classroom interventions, according to a 2023 study. They also conducted a cost-benefit analysis and determined that the $50 million literacy program created by the settlement was 13 times more effective than a typical dollar spent at schools.