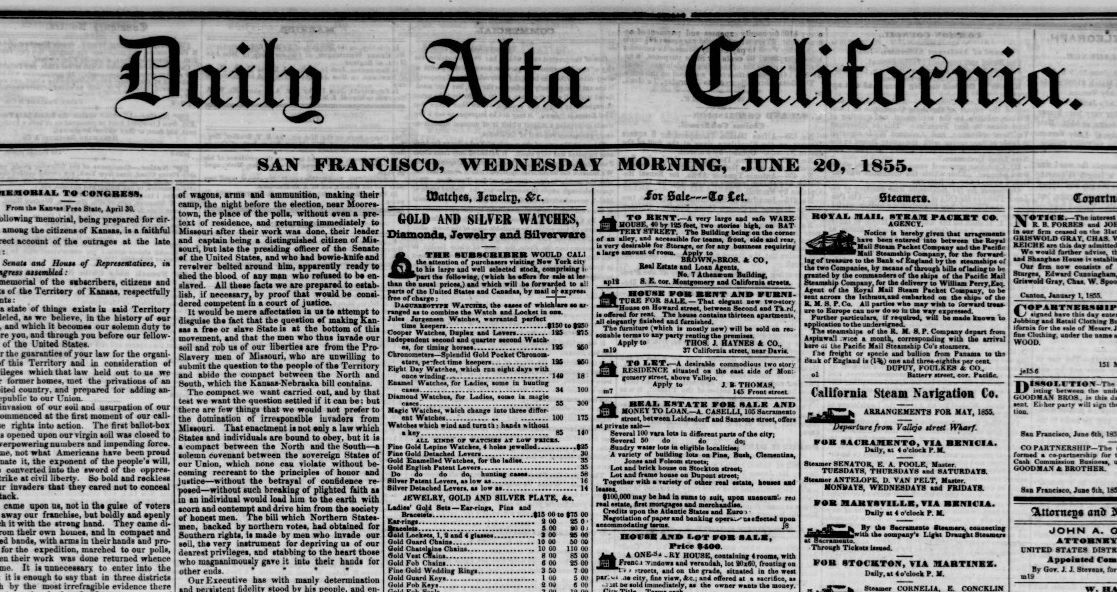

Daily Alta California

June 20, 1855

One of the greatest evils which has ever overtaken the city of San Francisco — the greatest because the parent of many other evils -- has been the overvaluation of property. It has not been properly confined to the city, but has manifested itself all over the State, and its results are to be noted throughout the length and breadth of the land. Now that Real Estate is "down," it may not be improper to say a few words concerning a subject which is of unusual interest to every permanent resident of California.

The available area of the pueblo of Yerba Buena for business purposes was very small. It extended only from about Pacific to California and from Montgomery to Dupont streets. We indicate the boundaries by streets which were laid out after the pueblo became the city of San Francisco. This space, although ample to accommodate the limited trade of 1846-7, proved wholly insufficient to meet the requirements of the wholesale immigration incited by the gold discovery.

By a natural law, the working of which never deceive, the prices of lots within the available area of the town, after those discoveries, rose enormously. Thousands of people were rushing into the State, the most of whom landed in this city. Thousands of tons of merchandise were poured in upon us, which had to find storage in town, and had to be disposed of here. Rents naturally rose to the most extravagant rate, and the price of land advanced with equal rapidity, although not in a proportionate degree. There was no telling where the thing would stop, particularly as money was most abundant, and there appeared to be no end to the immigration. So far the speculation was a legitimate one. Afterwards it assumed another character.

It was evident from the first that this state of things could not last forever. The capital which had been introduced into the country in the shape of merchandise was quickly turned to enlarging the limits of the city proper. Wharves were extended, and the water invaded on the one side, while hills were cut down and streets graded on the other. All this time rents still kept up, if not to their original point, at least to one which proved highly remunerative, and the immigration still continued larger. It still appeared that there was more room wanted, until at last San Francisco attained her present size. But the tide had turned, and rates at last, after a long period — unexampled, indeed, for duration in California — began to decline. They have been declining ever since.

The city of San Francisco is to-day out of all proportion to the State. Where we originally did not have enough room, we have now a superabundance, not merely for today or this year, but for years to come. The Real Estate speculation, which was originally a legitimate one, has for the last two or three years been merely a bubble, liable to burst at any time, and kept in a state of inflation merely by the activity of those interested in it. There is no reason why, with the present population and prospective increase of our State, fifty-vara lots two miles from the Plaza should command thousands of dollars, particularly when they are so situated as not to be available for purposes of agriculture. They should have a value, of course, and a vary considerable one. They may and do furnish legitimate objects of permanent investment for those who look forward to a return for their capital years hence ; but their intrinsic value it not to be rated by thousands.

We have been going too fast. We have followed out the speculative illusion to its full extent, and now we must stop. It is an indisputable fact that nearly all the prominent operators of 1852-3 are now bankrupt, and the mass of smaller men are utterly ruined. A year or two ago they thought themselves rich — they lived extravagantly, kept their horses and carriages, furnished their houses magnificently, and now — they have nothing. Seme few still hold out, and, with retrenched expenses, are wailing impatiently for a "rise." They will probably be sick of heart before it is realised.

But this system of overvaluation has not merely ruined those engaged in Real Estate operations : it has to a certain degree debauched the whole community. Parties who saw futures in land have neglected their legitimate callings to squat on fifty-vara lots, and drag out unprofitable years waiting for a settlement of titles. A recklessness of human life has been engendered, which has told very badly on the interests of the State at large, preventing many who would have made excellent citizens from coming to these shores. It has kept rates of interest extravagantly high, thereby eating out the vitals of the republic. A disposition to speculate desperately — in other words, to gamble— not merely in land, but in everything else, hat been fostered by it, and manifests itself in the frantic effort to "get whole," which have led men of high social standing to the commission of the most debasing crimes. In a word, it has vitiated the morals of the whole community.

The Real Estate market is at present in a curious position. The asking and offering prices for land show no approximation whatever to each other. Outside lots are unsaleable except at a ruinous discount from cost prices, while in some parts of the original plat of the city rates still keep up. The lot at the corner of Washington and Montgomery streets on which Burgoyne's building stands sold, a few days since, at auction, for $39,000, or about $1000 a front foot. At the same time, fifty-vara lots on the hill, which .were valued eighteen months ago at $12,000 to $18,000, to-day only command about $2500.

It is a singular fact, that a person owning a lot in the business part of the city, on which a brick building has been erected, can to-day borrow more money on it than it would sell for!

It is time that we began to awaken to the real value of property here. San Francisco is not New York, a city of half a million of inhabitants, with an immense population behind it; it is a small place— an important one, it is true, and destined one day to be the central point of the Pacific, but nevertheless a small one — the entrepot for a population of less than four hundred thousand people.

There is no reason why property in it should not rule at New York rates, and any attempt to force them up to such prices can only be a purely speculative movement which must, like all gambling— be it with dice, or cards, or Peter Smith titles — redound to the injury of the community at large.