Recently, Democratic voters crowded into a synagogue in Rohrabacher's district, eager to check out the candidates vying to replace him. Susan Becker knew what she was looking for. "I have to support the person who is most likely to win," she said. "It's just a shame that there are so many Democrats running, because we're going to split the vote."

Here's why Becker's worried. California's primary system puts all the candidates on one ballot. The two with the most votes go on to November, regardless of party. But in their enthusiasm to oppose Rohrabacher and Donald Trump, eight Democrats signed up, making it hard for any candidate to consolidate support.

That's why Michael Kotick dropped out, though his name is still on the ballot. "We have to be really smart about the math," he said. "We have to make responsible decisions on behalf of the community and on behalf of the party."

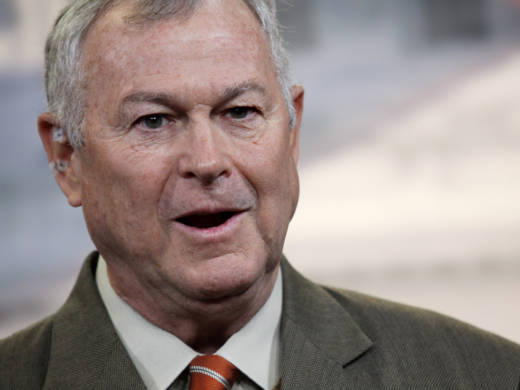

What made Kotick's decision so urgent was that, at the last minute, another Republican jumped into the race — Scott Baugh, a former Republican leader in the state Assembly and former chair of the Orange County Republican Party. Baugh has name recognition in this district where Republicans still have an advantage in registration.

If Democrats can't rally around a single candidate, they may have no one on the November ballot at all. At the synagogue forum, there was an awkward moment when the moderator asked one of the candidates why he didn't just drop out and throw his support to one of his fellow Democrats. The question got a round of applause.

Really, the only issue that the voters at this event really cared about was winning. And two Democrats seem viable.

One is Hans Keirstead. He's a stem cell biologist, but more relevant at this event, he has the endorsement of the California Democratic Party. But that hasn't helped clarify anything. Democrats are split. The national Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is backing Keirstead's chief rival, technology entrepreneur Harley Rouda.

The 48th District is not the only place where Democrats' glut of candidates has imperiled their chances. In another Orange County congressional district, Democrats were going at each other so hard that the head of the state party brokered a truce on negative advertising. But since everyone competes on the same ballot, Democrats are attacking Republicans, too. The idea is that if they can knock a couple of them down, it'll improve the chances of a Democrat making it into the runoff.

Raphael Sonenshein, the executive director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs at California State University Los Angeles, says everyone's now trying to figure out how to game the system, including voters.

For instance, a voter might think, "Should I vote for a candidate I don't much like so that our party doesn't get shut out? Or vote for that person so I can shut out the other party?" Sonenshein says that the top two system was intended to make primaries less partisan. "I think it hasn't really worked too well this year."

And it's not just Democrats who are facing a perilous primary next week. Republicans risk being shut out of both the races for governor and United States Senate.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))