T

he big but unsurprising news about BART this week is that its riders are unhappy -- in fact, more unhappy than they've ever been, if you go by the agency's record-low customer satisfaction survey numbers.

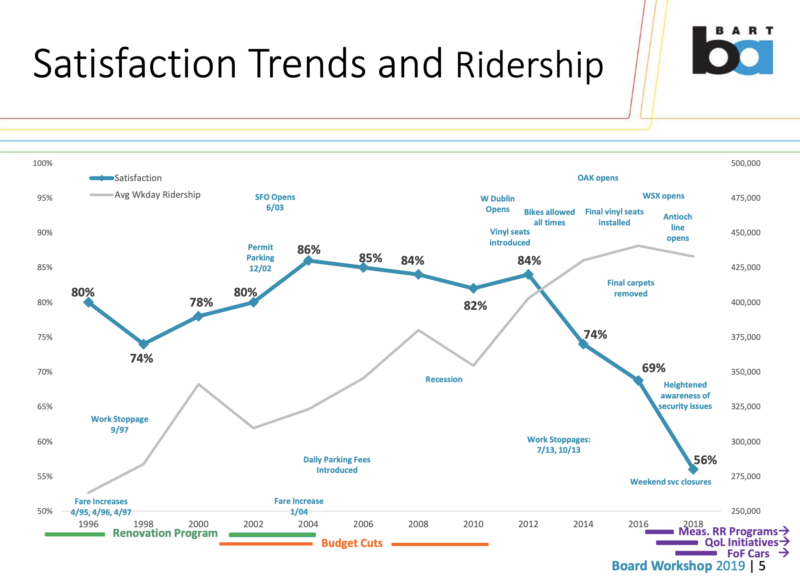

BART's overall customer satisfaction -- the total percentage of surveyed riders who say they're somewhat satisfied or very satisfied with the transit agency's service -- has been on a downward trajectory for years.

The surveys, taken every two years, showed that overall satisfaction number hovering between 84 and 86 percent from 2004 through 2012. Then, as ridership rose to record levels after the Great Recession, customer ratings of the service went into a free fall.

In 2012, the satisfaction rating was 84 percent. In the wake of two strikes in 2013, the number fell to 74 percent, tying a record low set in the late 1990s. In 2016, as ridership spiked and numerous breakdowns and service delays afflicted the system, the satisfaction number fell to a new nadir, 69 percent.

And the most recent survey -- conducted from Sept. 11 through Oct. 21, 2018, and to be discussed at a Thursday BART board workshop in San Franciso -- prompts the question, "How low can you go?" Just 56 percent of the roughly 5,300 respondents said they were "very" or "somewhat" satisfied with BART.

Driving that drop: anger over rampant fare evasion, a problem that BART has estimated costs $15 million to $25 million a year; displeasure with dirty trains and stations; unhappiness with the number of apparently homeless and mentally ill people who have sought out BART facilities as a haven; and concern about personal safety amid a spike in crime on the system.

The district's ridership reports back up the survey results.

BART, which depends on passenger fares for about 75 percent of its operating funds, has seen an overall ridership drop of about 6 percent during the last two fiscal years. Its average weekday patronage has fallen from a high of 433,000 to 414,000. The biggest declines have been seen in late-night and weekend ridership.

BART argues that there are signs that things are getting better: The agency says it has hired more workers to clean up stations, implemented a formal cleaner certification program and made visible progress improving conditions at some of the system's most notoriously troubled stations -- Civic Center and 16th Street/Mission in San Francisco, for instance.

The agency says that its new train cars will improve reliability and, by the very fact that they are shiny and loaded with new features like better air circulation and signage, will make riders happier.

And it points to one modest-sounding but unqualified success: The hiring of attendants to keep watch on the four elevators at Civic Center and Powell Street stations. Customer surveys suggest the public recognizes that conditions on those elevators -- often used as toilets by station denizens in the past -- have improved dramatically.

Still, in an appearance on KQED's Forum on Wednesday, BART board president Bevan Dufty told the district's patrons he was sorry.

"I want to apologize for the experiences that riders have had that have brought these numbers in so low," Dufty said. "It's not really a surprise because the problems the riders are seeing are what we're seeking to tackle and change."

He said part of the problem was the past failure to invest in the system -- an issue he suggested the district is on the way to solving thanks to a 2016 bond measure that will provide $3.5 billion to renew infrastructure. But he added, as other BART officials and directors have in the past, that the district and its customers are at the mercy of larger social forces.

"We are like everyone else in the Bay Area -- we are impacted by the crisis of homelessness," Dufty said. "This is something I've worked on, and we need the partnership of our cities and counties around the bay to address this, because we are a transportation agency, not a social service agency."

Dufty pointed to the deployment of San Francisco homeless outreach teams to the Powell and Civic Center stations over the past year as a success story, with team members finding help ranging from emergency shelter to clean socks for people seeking refuge on the BART concourses. That outreach effort is scheduled to expand next month, with a two-person team dedicated to the 16th and 24th Street stations in the Mission.

But Debora Allen, the board member representing central Contra Costa County, said in an interview she feels the survey results show the need for the district to take decisive action to respond to customer concerns. She said she wants to see the agency move to start hiring officers to fill about 25 empty positions in its Police Department and make it more difficult to get into the system without paying.

Allen, who like Dufty was elected to the board in 2016, said, "The last two years of continuous assurances that things will get better, that we're doing the right things -- that's no longer acceptable. Here we are, riders are coming back to us and saying, 'Yeah, we're even more unhappy now than we were two years ago.' We've got to move quickly. We've got to address the police positions. We've got to address the fare evasion. And we've got to figure out how we're going to close off the entrances to the stations" to non-paying riders.