An earlier district reform effort broke large, underperforming campuses into smaller schools that could, in theory, better support at-risk students. Since 2000, OUSD created scores of new schools, even as enrollment throughout the district sharply declined.

Want to know more? Read on...

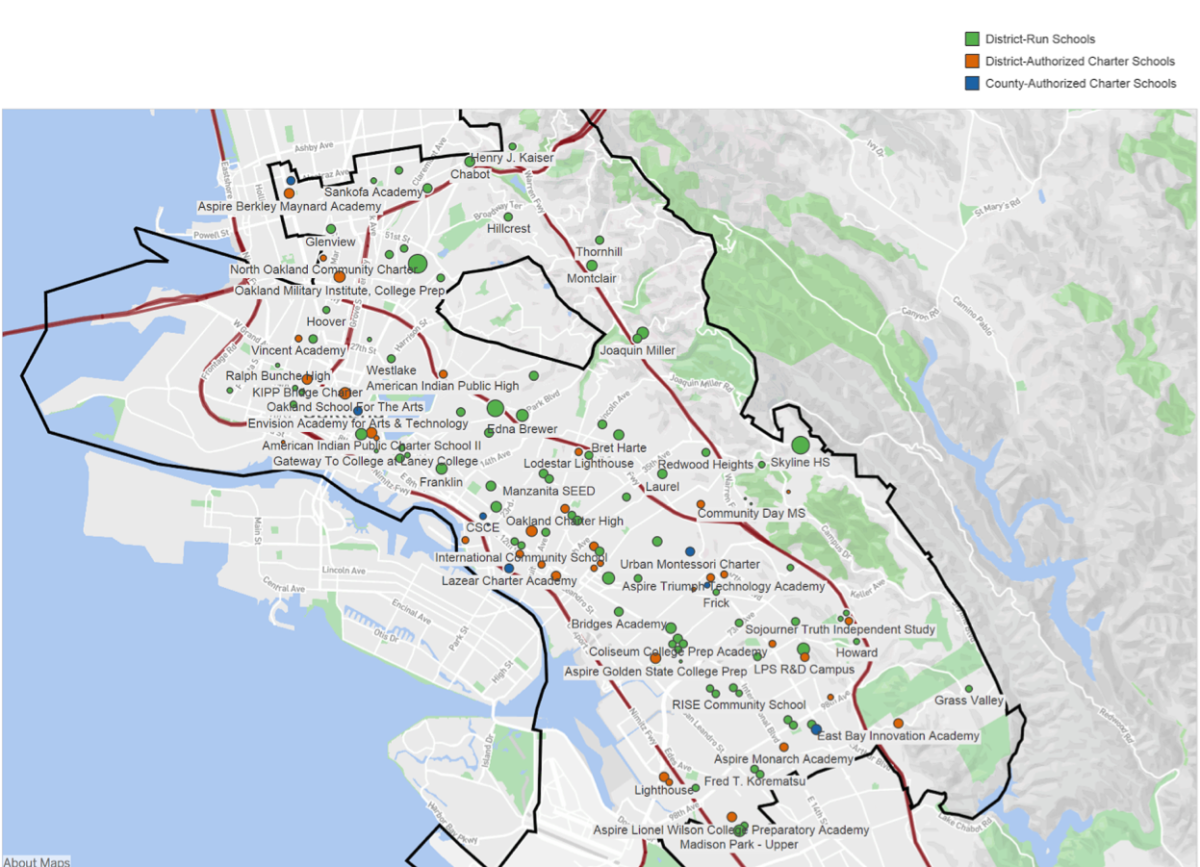

Oakland Unified School District has about 37,000 students in 87 non-charter public schools, or an average of roughly 425 students per school. That comparatively high school-to-student ratio is largely due to an earlier reform movement to create smaller, more intimate educational settings for students. Today, amid a serious budget crisis, district leaders are revisiting the premise of the small schools experiment, and have suggested paring down the number of schools by upward of 25 percent. Here’s a look at how Oakland ended up with so many small schools.

Does OUSD really have that many schools?

Yes. The number of public schools OUSD oversees is much higher than Bay Area districts of similar size. Take nearby Fremont Unified, which has just over 35,000 students but only 42 schools. Or San Jose Unified, where about 32,000 students attend 46 schools.

Of course, Oakland still has its fair share of larger schools. About 1,800 students were enrolled at Skyline High School during the 2017-2018 school year, and nearly 2,000 at Oakland Tech. But a good number of district schools have fewer than 300 students. Among them: Roots International Academy, one of the schools slated for closure, which now has just about 260 students and Sankofa Academy, which has fewer than 200.

Why were so many new schools created?

Since 2000, the district has opened a huge number of small schools, even as its enrollment dropped by about 45 percent. Here’s how it unfolded:

In the late 1990s, Oakland’s public school district was dealing with many of the same issues it faces today, including financial problems, low test scores and high teacher turnover. Most of the under-performing schools were concentrated in the city’s “flatlands” neighborhoods and primarily attended by lower-income, minority students.

Unlike now, though, many of those schools were bursting at the seams and straining to manage far more students than they were designed to accommodate, particularly elementary schools.

In light of these overcrowded and sometimes chaotic conditions, a group of concerned parents teamed up with an alliance of religious and civic leaders, called Oakland Community Organizations, to push for a major overhaul of the district’s most troubled campuses.