Episode Transcript

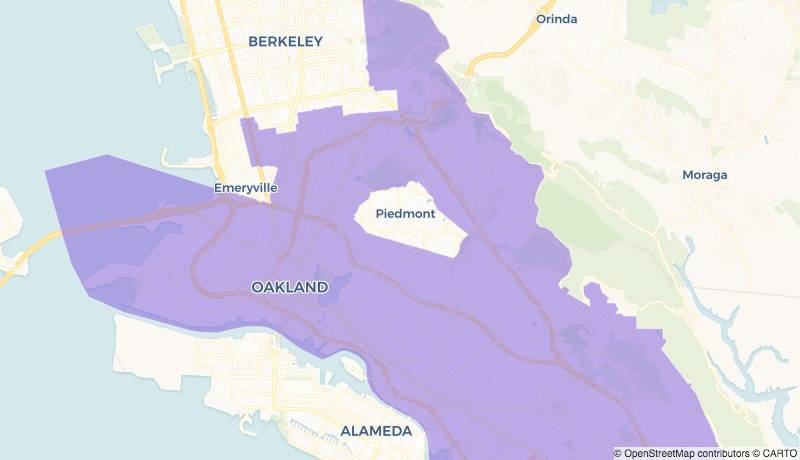

Olivia Allen-Price: The city of Piedmont in the East Bay is a bit of geographical oddity.

David Levine: I looked at a map and I saw that Piedmont was almost like a doughnut hole in the center of Oakland.

Olivia Allen-Price: This is David Levine, our question-asker today. On the map, he saw this tiny city, not even two square miles in size, surrounded on all sides by the city of Oakland.

And if you take a close look, the borders of Piedmont seem to make no sense. Instead of following streets or physical landmarks — like the borders of most towns do — in Piedmont, the borders snake around — sometimes through the middle of homes. All this got David wondering ….

David Levine: Why is Piedmont a separate city from Oakland?

Olivia Allen-Price: This is Bay Curious, the podcast that explores the Bay Area one question at a time. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. This week we’re bringing you the wild, unexpected origin story of the city of Piedmont. This story first aired in 2019, but it’s a topic we still get questions about on the regular. So, Piedmont fans, Piedmont detractors, and all you generally curious people — stick around for some answers.

SPONSOR MESSAGE

Olivia Allen-Price: Now, this is a story about Piedmont, of course. But as soon as we started digging, we found out….

Chris Hambrick: … The story of Piedmont starts in Oakland.

Olivia Allen-Price: … Reporter Chris Hambrick brings us the tale.

Chris Hambrick: In the late 1800s, Oakland incorporated, going from ranch land and small settlement clusters to becoming an official city. Almost immediately, it started to grow.

(music begins)

Steve Lavoie: Oakland leaders were under a very ambitious program to enlarge the city’s boundaries and increase the population.

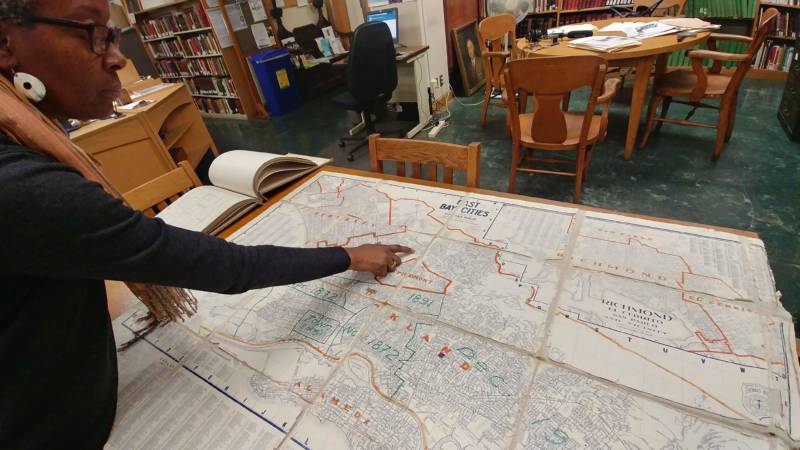

Chris Hambrick: That’s Steve Lavoie. He’s an Oakland librarian who curated an exhibit on Piedmont history. This program to expand Oakland’s boundaries was called the Greater Oakland Movement. City leaders wanted to add more land and more residents.

Steve Lavoie: This movement was not so much motivated by economic interests, but it was motivated by the anti-monopoly group who felt that small cities were ripe for corruption.

Chris Hambrick: They thought the smaller the city, the greater the chance that greedy folks would do something like raid the treasury or discourage competition among businesses.

(music fades)

Steve Lavoie: The original plan would have created the largest city on the Pacific coast at the time.

Chris Hambrick: This large city could only come together if they could convince all of the neighboring towns and communities without their own government to join Oakland.

(music begin)

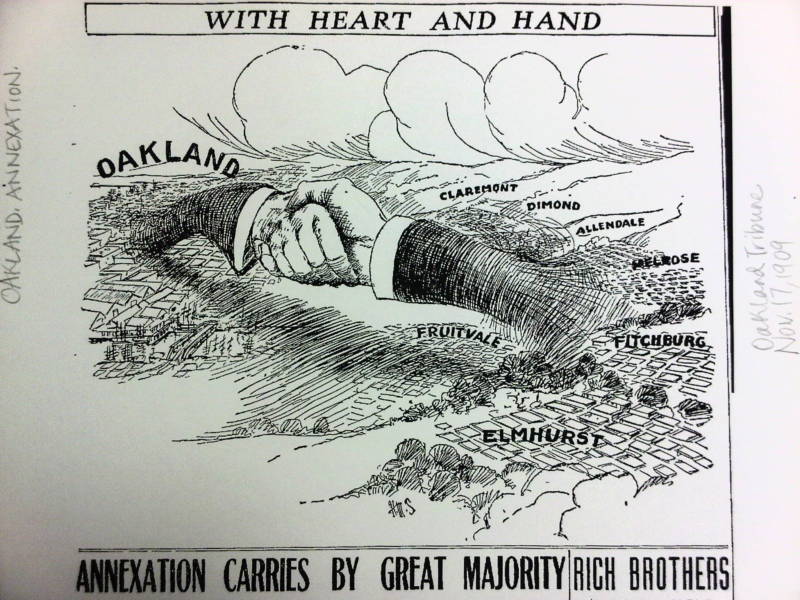

Chris Hambrick: Oakland started at about 170 city blocks in size. It grew from there by absorbing surrounding towns whose names you might recognize as neighborhoods today.

Voices: Temescal. Brooklyn. Fruitvale. Elmhurst. Melrose.

Chris Hambrick: They tried to get Berkeley, but Berkeley said, “No, thanks.” Each annexation required a vote by people in the town.

Dorothy Lazard: You know, it wasn’t like an aggressive kind of corporate takeover or anything. It was more negotiation with various town councils.

Chris Hambrick: That’s Oakland librarian Dorothy Lazard. Oakland city leaders kept eyeing new territory, and soon Piedmont was squarely in its crosshairs.

Steve Lavoie: The city council took a measure to vote, an annexation of all the land in what is now Piedmont, and a whole bunch of other East Oakland hamlets.

Chris Hambrick: Oakland City Council set the vote on annexing Piedmont for January 1907. But then something went wrong. In their paperwork, they failed to name one of the districts that they wanted to annex, and the vote was postponed until March. This left a really big opening for mayhem.

(dramatic music starts)

Steve Lavoie: In the meantime, a group in Piedmont who opposes annexation jumped on the opportunity to try and incorporate Piedmont as a way of preventing annexation into Oakland.

Chris Hambrick: During the delay in Oakland’s vote, some Piedmont residents, a mix of bohemian artists and businesspeople, filed a petition to hold their own election to become a city. If they could beat Oakland to the punch, they hoped Piedmont would remain rural and undeveloped. Piedmont historian Ann Swift says convincing other Piedmont to incorporate was no easy feat.

Ann Swift: They’re having meetings every other night, practically trying to rally the troops and get everybody excited about creating this new city. But there was also opposition.

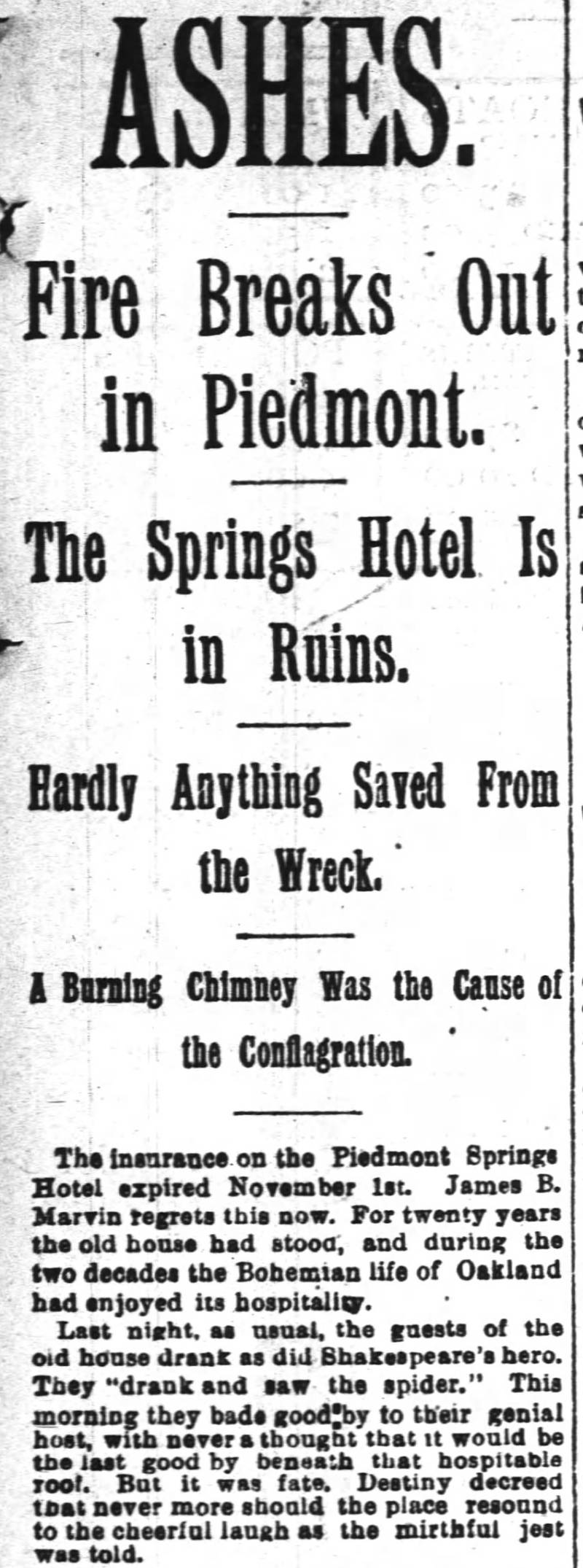

Chris Hambrick: Something that happened back in 1892 weighed heavily on the minds of voters.

Ann Swift: The Piedmont Springs Hotel, which was a great huge three-story white clapboard edifice that sat in the center of the city, caught fire early one morning in November.

Chris Hambrick: That Grand Hotel was Piedmont’s biggest tourist attraction, a place where wealthy San Franciscans came to relax. Piedmont didn’t have city services, so Oakland’s fire department was summoned to come out the fire.

Ann Swift: Because in those days, there were no fire hydrants. You had to bring the water with you. Well, imagine a team of horses dragging a big tanker full of water up Oakland Avenue, for instance. Very, very difficult and slow going. So by the time the fire wagons got to the hotel, they were just sitting with everybody else, watching the embers burn.

Chris Hambrick: It took Oakland’s fire department a whopping two hours to get to the hotel.

Ann Swift: It was completely gone. And that was what happened if your house in the Piedmont hills caught fire. So Pidemonters were adamant about wanting their own fire service.

Chris Hambrick: All the Piedmont residents agreed that they needed a better solution for fire response, but they differed on whether better meant being a part of Oakland or figuring it out as their own city.

Ann Swift: Piedmont had no experience with levying taxes and evaluating property and providing all the city services, and so all of that was going to have to be created. And there was a sizable part of the city who thought there was no need to go through that.

Chris Hambrick: The big vote on whether Piedmont should incorporate happened in January 1907.

Ann Swift: Eighteen more men voted to become a city, than voted to not become a city.

Chris Hambrick: But here’s where it gets tricky. Oakland’s vote to annex Piedmont still went forward, and in March, a majority of Piedmont residents voted to join Oakland. But this was impossible, now that Piedmont was its own city.

Ann Swift: So the only thing that the opponents in the Piedmont hills can do is to hold an election to disincorporate a city. So they hold another election in September, and more people vote to become part of the city of Oakland, to disincorporate Piedmont than vote to stay a city. So I always ask the school kids, well, so how come I’m not talking to you in Oakland City Hall? It’s one of those little nuggets of lore that people don’t know much about or care much about until they have to. It requires two-thirds vote of the people to disincorporate a city, and they failed to get two-thirds.

Chris Hambrick: Piedmont stayed a separate city, with its edges within and out of Oakland. This is because, in their haste to file paperwork to incorporate Piedmont, proponents grabbed the only map they had on hand to define the boundaries. It was a map of the sewer lines that snaked underneath the houses in Piedmont.

Chris Hambrick (in tape): So what does that mean for the borders of Piedmont today?

Dorothy Lazard: It means that there are 136 parcels, a portion of which are in Piedmont and a portion of which are in Oakland.

Olivia Allen-Price: So, Chris, it sounds like Piedmont will continue to be sort of this city within a city, you know, the Vatican of the East Bay, if you will. Now, I know our question-asker had a few concerns about how Oakland and Piedmont interact. Did any of those issues sort of come to light for you as you were reporting the story?

Chris Hambrick: I learned that both Oakland and Piedmont have an agreement to back each other up when it comes to fire and police services and that Piedmont pays the city of Oakland to use their library since they don’t have any of their own. But when it comes to resident-to-resident interaction, that relationship was a little bit more strained than people would admit on tape. In general, Piedmont residents enjoy having this small-town feel within their city. They know their public officials by name. They know their neighbors. But it seems like some Piedmont residents feel judged for being able to live that way. And on the Oakland side, there’s this feeling that Piedmont residents have been more deliberate and separating themselves and they did that along race and class lines.

Olivia Allen-Price: And why do you think there’s this perception? Where does that come from?

Chris Hambrick: I think it kind of stems from back in the 1920s. Piedmont had a police chief by the name of Burton Becker, and Burton was an active member of the Klu Klux Klan. He held Klan meetings inside of his house, and at a time when Oakland had banned the Klan because the jurisdiction was different, he was shielded a little bit from persecution, being in Piedmont. He could not be banned because Piedmont is its own city. And then, after World War II, when many African Americans were migrating to the Bay Area from the American South, Oakland’s housing stock was more affordable than Piedmont, so people ended up settling in Oakland. And Piedmont residents are 68% white and 21% Asian, according to the 2020 Census. Compare that with Oakland, which has much larger Black and Latino populations. Some people view this as evidence that Piedmont created a community that excludes based on race and class.

Olivia Allen-Price: And I understand there hasn’t been any like super serious effort to, you know, merge Piedmont and Oakland. But there was a social media campaign a few years back. Can you tell me about the Liberate Piedmont movement?

Chris Hambrick: So a high schooler named Noah Goldstein wanted to explore the possibility of merging Piedmont and Oakland because he felt like Piedmont residents enjoy the benefits of Oakland without having to pay for them. And Piedmont residents pay hefty taxes to support their schools and their city services but they pay that money to the city of Piedmont.

Olivia Allen-Price: But it sounds like Piedmont residents weren’t super keen on this idea of becoming a part of Oakland.

Chris Hambrick: Yeah, that’s what I gather. They have a degree of comfort with the way that their life is now. And even though the city founders weren’t able to keep that development from happening, you know, the area’s just 1.7 square miles. And so they did succeed in creating that small-town feel inside their city.

Olivia Allen-Price: All right. Well, Chris, thanks so much for looking into this one for us.

Chris Hambrick: You’re welcome.

Olivia Allen-Price: A big thanks to Bay Curious listener David Levine for asking this week’s question.

Olivia Allen-Price: Liam O’Donohue, the host and creator of the East Bay Yesterday podcast, was a big help with the research on this story. If you haven’t checked out Liam’s podcast yet, I highly suggest you give it a try. Just search East Bay yesterday.

Olivia Allen-Price: Bay Curious is produced in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. The show is made by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale, and me, Olivia-Allen Price. Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED Family.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Thanks so much for listening.