The San Francisco Port Commission on Tuesday gave the city the green light to build a temporary multiservice homeless shelter on a large Embarcadero lot near the Bay Bridge, a move fiercely contested by neighborhood residents.

S.F. Port Commission Approves Controversial Embarcadero Navigation Center

Following more than five hours of impassioned public comment from supporters and opponents, the four commissioners in attendance voted unanimously to lease the 2.3-acre site to the city for its proposed Embarcadero SAFE Navigation Center.

“What I see today is just the beginning of a journey,” said Commissioner Doreen Woo Ho, stressing that proper execution of the project would be critical.

She reminded concerned residents that the lease is temporary, and that the Port still plans to develop the prime piece of real estate — Seawall Lot 330 — for longer-term, more profitable use.

“We are here to hopefully demonstrate that if this navigation center works in this kind of neighborhood, in this kind of city, then it will work everywhere in the city,” she said.

The 200-bed facility will be the city’s largest navigation center, providing a range of round-the-clock supportive housing and rehabilitative services to the homeless.

The commission’s vote caps a succession of heated, sometimes vitriolic community meetings about the project, attended by staunch advocates for and against the plan. The strongest pushback comes from residents of the South Beach, Rincon Hill and Mission Bay neighborhoods, amid concerns that the facility will transform the tourist-heavy neighborhood into a dirty, crime-ridden area and reduce property values.

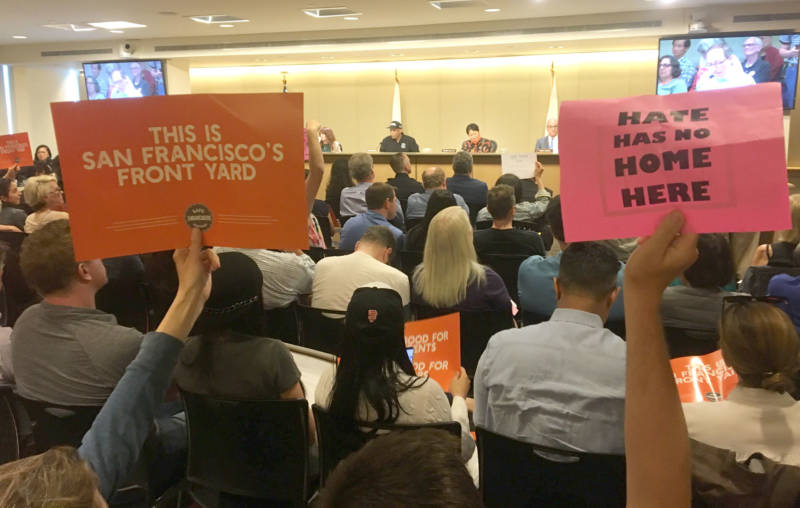

Both sides came out in force on Tuesday, packing the commission hall and spilling into a boisterous overflow room. Attendees gave hours of often emotional testimony as their supporters hoisted competing orange and pink signs with messages like “Not good for residents; not good for visitors” and “Hate has no place here.”

With the lease now secured, the city plans to break ground on the center this summer, with hopes of opening it in the early fall, although the expected litigation could delay that schedule.

The city is leasing the Port-owned land for two years for nearly $37,000 a month, and will have the option of renewing for an additional two years if it can demonstrate the center has helped reduced homelessness.

At the last community meeting a week ago, city officials tried to appease opponents by promising dedicated police patrols near the center, splitting the original four-year lease half and scaling back the proposed facility to 130 beds, consistent with the size of other navigation centers, and then ramping up to 200 beds over six months.

But that did little to allay neighbors’ concerns.

“It’s not even that I personally am against the navigation center at that particular location,” said Judy Lin, who’s lived in South Beach since 2008. “It’s just the fact that the city has not listened to or addressed any of our concerns when it comes to the size of the facility, the length of the lease, the policies with respect to drug use or curfew or any of that.”

Lin said the roughly dozen community meetings she’s attended with city officials felt like “talking into a black hole.” A newly formed neighborhood group she’s part of, called Safe Embarcadero for All, intends to sue the city in a last-ditch attempt to stop the project from moving forward.

“We could have worked together to come up with a solution that helped the homeless and that the neighborhood can support,” she said. “But instead, the mayor is just ramming this down onto the neighborhood without addressing any of the concerns.”

But for supporters of the plan, Tuesday’s vote signaled a major step forward in addressing the city’s worsening homeless crisis.

“This crisis belongs to all of us equally, no matter what neighborhood you live in,” said Carmen King, who lives next to a homeless shelter in the Tenderloin and insists that safety has never been an issue. “People die sleeping outdoors, and that’s the real issue here today. … All of us are safer when everyone in San Francisco can sleep indoors.”

First proposed in early March by Mayor London Breed, controversy over the center erupted weeks later after a group of neighborhood residents started an online fundraiser to challenge the plan in court. The group has already hired a local land-use attorney who plans to file an appeal under the California Environmental Quality Act in an effort to block construction.

That campaign, in turn, provoked a dueling fundraiser among supporters of the proposal, one that quickly eclipsed its rival and has now raised more than $175,000, including major contributions from several high-profile tech CEOs.

The two fundraisers underscore just how divided San Franciscans are on the issue of homelessness and how to address it. And that makes new legislation, introduced earlier this month by San Francisco District 6 Supervisor Matt Haney — which would require a navigation center in each of San Francisco’s 11 districts — all the more controversial.

“Ultimately I think this is going to be a positive thing for the many people that it serves,” said Haney, who supports the Embarcadero facility, which will be in his district. “And also for the community. I expect in a year or two the people in this community will look around and say there’s actually less people who are living on the streets in this neighborhood because of this navigation center. And they should be proud they had the opportunity to be part of the solution.”

San Francisco opened its first homeless navigation center in 2015 and currently operates six throughout the city. Unlike traditional shelters, the centers allow occupants to bring pets and don’t make them leave in the morning.

The proposed navigation center in the Embarcadero is a critical part of Breed’s campaign pledge to open 1,000 new shelter beds by the end of 2020.

Supporters of the waterfront shelter plan, including some who live in the neighborhood, have accused opponents of being selfish and heartless. But many of the mostly middle-aged residents who stayed for the duration of the hearing insisted they were in full support of more homeless services. They argued, though, that it was irresponsible of the city to open a large shelter in a neighborhood filled with tourists and families, where homelessness is currently not a major issue.

“I actually was going to give up my time to speak until I was just called a racist, a bigot, a class elitist for not wanting to give up my backyard for drug use, drug sales, mental illness and busing additional homeless into our neighborhood,” said James Dorsch, who lives a stone’s throw from the site. “Yeah, I don’t think a lot of people would want those things in their backyard. That doesn’t make someone a bigot. That doesn’t make someone a racist.”