Unaccompanied migrant children are now being held in U.S. custody for more than twice as long, on average, than they were four years ago, according to government data.

Wait Times for Migrant Children in U.S. Custody Spiked in Recent Years, Records Show

In the 2015 fiscal year, officials with the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the agency tasked with caring for unaccompanied minors, released children to sponsors within an average of 34 days. But in the first half of this fiscal year, that average jumped to 77 days.

While officials point to the surge of unaccompanied minors crossing the US.-Mexico border as contributing to delays, immigration advocates argue that stricter screening procedures have exacerbated the situation by deterring more sponsors from coming forward.

Regardless of the reason for the longer custody, care providers and advocates say children who have crossed the border without a parent or legal guardian have likely already endured trauma, and postponing their release can cause more damage, both psychologically and physically.

“The idea that we would take custody of a child and then put them in a dangerous position where they are undergoing more harm or trauma should be completely abhorrent to us as a nation,” said Milli Atkinson, supervising attorney at the Immigrant Center for Women and Children in San Francisco.

ORR officials reported in March that they had received about 32,000 children from immigration authorities in the last six months. If that surge continues, the number of unaccompanied children this year could be the largest in history, officials said.

Atkinson and others worry that as government-contracted facilities become more crowded and staff are stretched increasingly thin, minors face higher risk of abuse, depression and health problems.

“It’s just a recipe for disaster,” said Atkinson.

Last month, a 16-year-old boy from Guatemala fell ill and died while held at a shelter in Texas. And in recent years, thousands of migrant children have reported being sexually abused or harassed while in U.S. custody, often by other detained children.

Pamela Baez, a former life-skills trainer at Cayuga Centers, a nonprofit agency serving upward of 900 unaccompanied minors in New York City, said the children she cared for were desperate to be reunited with their family members.

Between 2015 and 2018, when Baez worked for the agency, she said she saw a noticeable increase in the length of time children were detained.

“The case manager would come and be like, ‘Unfortunately, now you have to stay two more months,’ to the point that children started asking if they could be deported back to their country,” she said. “Because they were just over it, they were tired, they were emotionally drained.”

The children at Cayuga Centers are housed with foster parents and attend daily classes and mental health counseling at the agency. But Baez said many kids are traumatized, and keeping them away from their families aggravates their distress.

“I would see how they are suffering," she said. "I would have kids in my classroom and the next day I’d find out that they had even harmed themselves. Some kids were even trying to commit suicide.”

A spokesman for Cayuga Centers said the safety and well-being of children is the agency's top priority, and that children are better off with transitional foster families than being detained at residential shelters, where most unaccompanied minors end up.

Children apprehended at the border without a legal guardian are sent to one of over 100 facilities under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees ORR, and they remain in custody until potential sponsors are vetted to ensure kids are released to a safe environment.

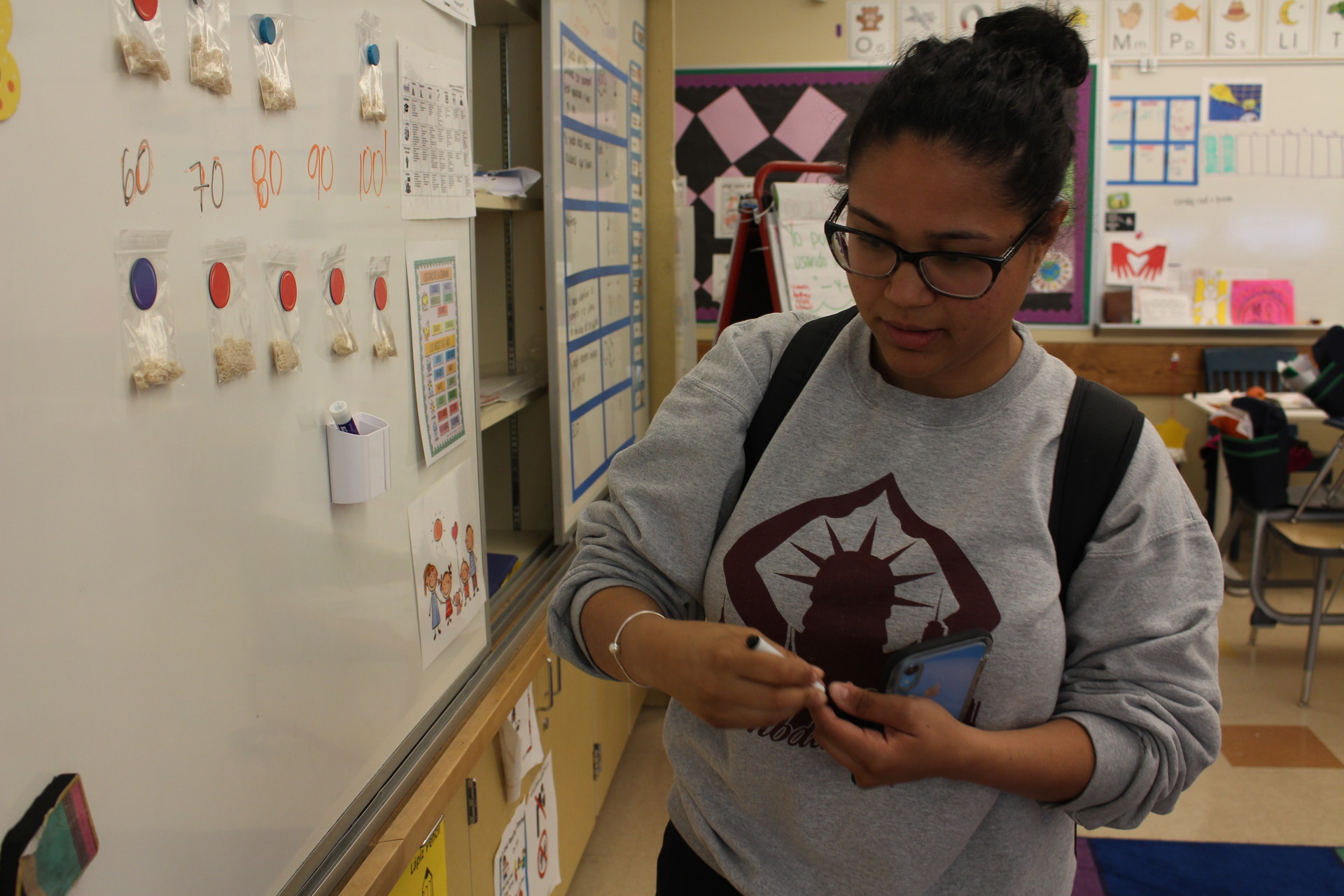

Angel, a 17-year-old Guatemalan boy, spent nearly three months detained at a shelter run by a for-profit corporation in southern Florida. He recently attended a legal orientation program in San Francisco’s Mission district with his cousin Santos, who sponsored his release. (KQED is not using the family’s last name because of their immigration status.)

Santos, a construction worker, said Angel hasn’t talked much about what happened at the shelter.

“Time will heal his wounds, the trauma that he’s carrying,” said Santos, a father of two, who has lived in the Bay Area for 14 years.

To get custody of Angel, Santos and his wife had to provide the government with their fingerprints, biographical information, proof of income and a series of other documents.

“They know everything about me, they know where I live,” he said. “The government asks for a lot of paperwork, but if we don’t turn it in, they don’t give us the boy.”

Santos and his wife decided to risk providing their personal information, even though they knew it could land with immigration enforcement officials. But advocates say that since last year, when ORR agreed to share information about potential sponsors with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, many undocumented families are not claiming children out of fear they could be deported.

Previously, service providers felt comfortable reassuring undocumented sponsors that they and other household members wouldn’t become targets of immigration enforcement. But now, ICE runs criminal and immigration background checks as part of the vetting process, said Melissa Hastings, a policy advisor at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Washington, DC.

“While thorough vetting of sponsors is beneficial, we do remain deeply concerned about the information sharing between ORR and ICE,” said Hastings. “[It] continues to represent a significant shift in past practices and it is resulting in serious impacts to children, including prolonged stays in U.S. custody.”

In February, Congress limited the use of the ORR data for immigration enforcement after reports that ICE had arrested 170 immigrants who were trying to get minors out of U.S. custody. Most of those potential sponsors had no criminal record.

But advocates say those restrictions are set to expire in September.

“The climate towards immigration right now in this country is inducing a lot of fear for people who in the past may have stepped forward to sponsor a child,” said Atkinson, the San Francisco attorney.

Over the last year, the Trump administration expanded requirements for who must be fingerprinted in the sponsor’s household. But the government backtracked after the number of unaccompanied migrant children in U.S. custody ballooned to more than 14,700.

Currently, only sponsors who are not the child’s parents or legal guardians must submit their fingerprints for background checks — unless risks and other factors that could harm the child are revealed.