When asked by LAHSA what would have kept survey participants from becoming homeless, the most common answer was “someone who cared about me.”

Some homeless black residents in Monterey County say that is exacerbated by the lack of black people in decision-making positions in programs that serve the homeless.

Victoria Powers, a black woman in her 30s who has lived in Chinatown since she was 15, agrees. Latinos working in shelters gave special treatment to the Latinos living on the street, she said, but the same was not true for black people hired by the shelters.

“You’d think they’d want to help their people, but they’re too afraid of getting fired,” she said.

“It just shows that racism still, in some form, exists,” added Shawn Payton, a black homeless resident in Chinatown and Harraway’s cousin. “The whites, the Mexicans (working in shelters and housing) are going to look out for their own.”

Powers and others said they felt shut out of services, that they weren’t told certain programs existed until another black person clued them in.

“Where’s the money going?” Powers asked. “We don’t see it.”

Reyes Bonilla, executive director of Monterey County’s Community Homeless Solutions, which runs the transitional housing program Harraway went through, said he often encounters that perception by black people coming into transitional housing programs. However, he denied that race factored into the way clients are treated, calling it a misconception.

Berg noted that this sense of exclusion is not unusual among black homeless people, however, and added that there are ways to combat it.

“It’s really a matter of working with the black community to make sure, to know that these resources exist and work with people to make sure they’re as friendly as possible,” Berg said.

Working with people experiencing the programs as well will go a long way to improving gaps in the program and helping streamline the process, continued Berg.

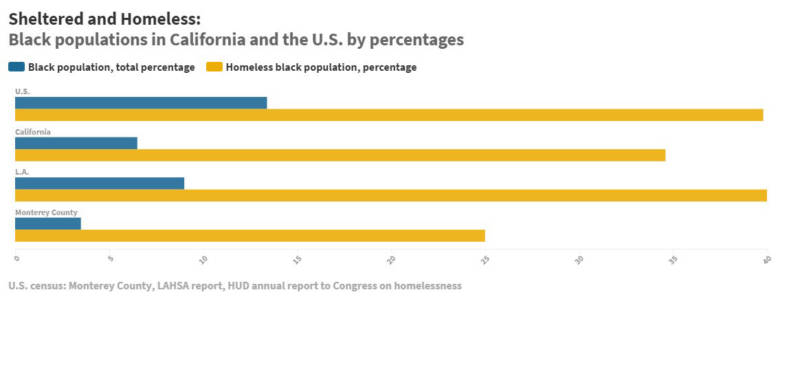

Robinson, at the Coalition of Homeless Services, noted that the coalition has seen a gap in the number of black people enrolled in their services versus the number of white people enrolled, evidenced in its 2018 report on racial disparities in homelessness. While black people outnumber white people 12-to-1 among the homeless population, they only enroll at a rate of 3-to-1.

However, once enrolled in the program, the percentage of positive outcomes for black and white clients are nearly uniform, with 8.59 black people graduating to permanent housing for every 10 white people.

“Once you enter the system, your chance of a positive outcome is the same as anyone else,” Robinson said. “I think that’s an important point, though, that we should do a better job of outreach or building trust. We are falling short.”

Kate Cimini is a multimedia journalist for The Californian. This article is part of the California Divide project, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequality and economic survival in California.