With two weeks to go before Election Day in California, businesses, labor unions, mega-wealthy political donors and other coalitions of deep-pocketed interests seeking a say in state lawmaking have opened the spigots.

Adopting benign names like “Coalition to Restore California’s Middle Class,” “Keep California Golden” and “Taxpayers for Ethical Government,” groups are allowed to raise and spend unlimited sums of cash in state elections so long as they don’t coordinate their activities with any candidate. From the beginning of the year through Wednesday, these “independent expenditure” committees have spent $12.5 million to determine who wins seats in the state Legislature.

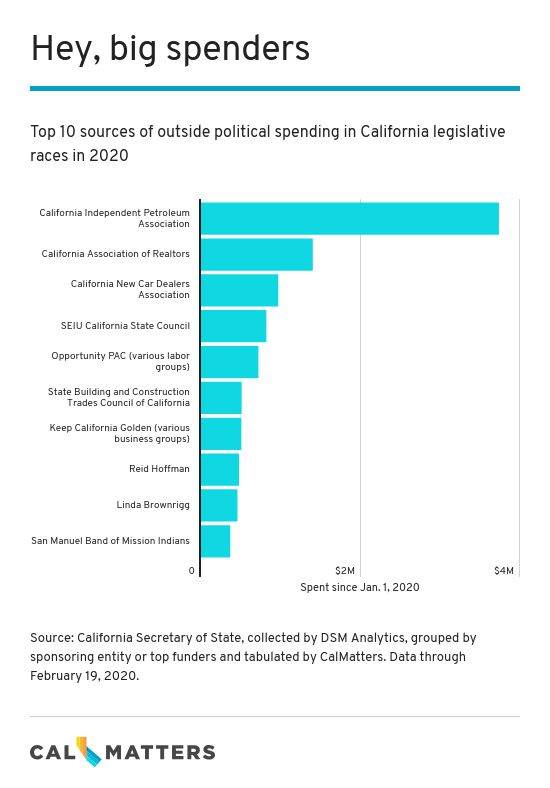

And though California may be known as a bastion of green, progressive policy making, this year’s money wars are dominated by the industries of the old guard: Together, oil and gas producers, Realtors and car dealers are responsible for nearly half of all outside spending.

Following the money traces the fault lines of California politics, where the biggest conflicts aren’t Democrat versus Republican, but different shades of blue. The most expensive race so far is not a purple swing seat in coastal Orange County or the burbs of San Diego, but a Democratic lock in east Los Angeles County. The main players: organized labor versus virtually every business interest in the state.

The $12.5 million-and-counting on legislative races isn’t much by presidential standards. Last year, White House contenders spent roughly eight times that sum in California — $99.3 million.

But in less publicized contests further down the ballot, where the outcome may hinge on name recognition alone, that kind of money can go a long way, said Doug Morrow, who runs the political research group DSM Analytics.

That’s particularly true if the fire hose of cash is aimed at just a handful of contested seats. Which it is.

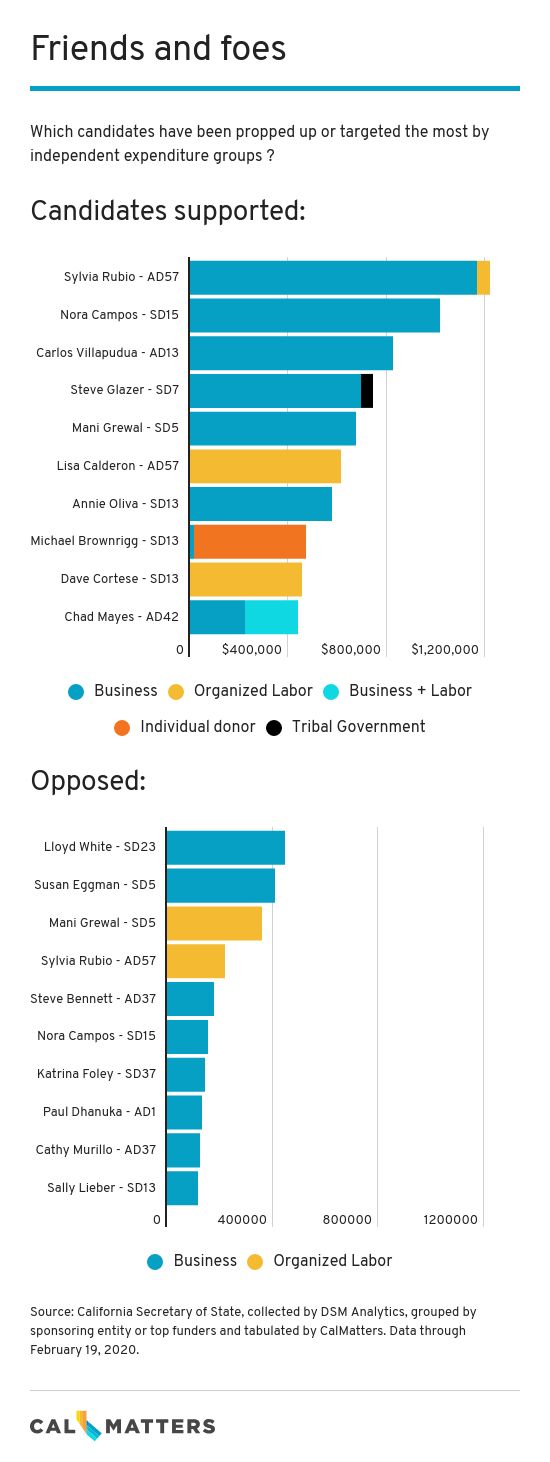

According to campaign finance data published by the state and tabulated by Morrow, seven races — four for the state Senate and three for Assembly seats — have received nearly three-quarters of all the money spent by outside groups so far.

State law caps the amount that anyone can contribute directly to a legislative campaign at $4,700 per election (primary and general contests are considered separate elections). Because independent expenditure committees can spend as much as they can raise, they are the preferred avenue for interest groups hoping to have their say before Election Day.

Morrow said he has never seen so much money pumped into California legislative races this early in the year. Why the mad dash? California’s earlier-than-usual presidential primary and voters’ habit of casting their ballots weeks out from Election Day.

“They know people are going to put their ballots in the mail,” he said. “You’ve got to make your case and close that deal early on.”

Picking the right 'brand' of Democrat

In the most heated (and expensive) battles for California legislative seats, the key question for big outside spenders isn’t whether to back a Republican or a Democrat — but which kind of Democrat.

It’s a reflection of the Democratic Party’s dominance of state politics in California. For businesses that might have once prioritized the election of Republicans, backing a business-inclined Democrat is now often their best bet for ensuring a friendly vote in Sacramento.

“The goal is to get your particular brand of Democrat to emerge in the run off,” said David Townsend, who directs the Californians for Jobs and a Strong Economy, a committee that backs moderate Democrats. In races where business interests and organized labor pick different candidates, he said, “it’s an arms race. When one side spends more, you have to spend more.”

As of this week, the most expensive arms race in the state is the contest to replace Assemblyman Ian Calderon, a Democrat from Whittier in southeast Los Angeles County. The outside money tally so far: more than $2 million.

Two dynastic names have attracted all the outside spending. Lisa Calderon, the incumbent’s stepmother, has the backing of labor groups like the Service Employees International Union, while Sylvia Rubio, the sister of two state lawmakers, has financial supporters that include oil and gas producers, credit unions and charter school advocates.

But it’s a crowded field. Calderon and Rubio are running against six other Democrats and one Republican. In state and congressional races in California, only the top two candidates move on to the November general election. And though registered Democrats outnumber Republicans in the district by more than two-to-one, the sheer number of Democrats in the field may sufficiently dice up the Democratic vote to give Delphine Martinez, the lone GOP candidate, one of those two spots.

Thus, the race is on to pump campaign cash into the district now, while the contest is still up for grabs.

According to Morrow’s “independent expenditure” tabulations, more than $1.1 million has been spent to boost Rubio, making her the biggest beneficiary of outside spending in any legislative race in California this year. More than $218,000 has been spent opposing her.

Labor groups have spent some $615,000 to help Calderon.

“In a race like that, where fewer than 100,000 people are going to vote, that’s a lot of money,” said Townsend, whose PAC is backing Rubio.

Oil is king

Nevermind California’s green cred; the petroleum industry has been the state’s biggest source of independent campaign spending this year.

The California Independent Petroleum Association’s two major committees (somewhat duplicatively called the “Coalition to Restore California’s Middle Class” and the “Restore California’s Middle Class Coalition,” respectively) have spent more than $3.7 million on state legislative races. That’s 29% of all independent spending in the state.

Julie Roberts, a spokesperson for Coalition to Restore California’s Middle Class, declined a request for an interview, but said in a written statement that the committee “supports leaders who have protected California jobs and the middle class and share our commitment to policies that help businesses thrive.”

Even that number may understate the oil and gas industry’s financial footprint. Many of the state’s largest political action committees are not sponsored by a single industry, but are joint ventures that pool the political spending of like-minded businesses. Townsend’s committee, for example, has been the eighth biggest independent election spender this year. Over the last two campaign cycles, its largest contributor has been Chevron.

The industry probably can’t count on a wholesale reversal of state climate policy through their legislative spending. But in an era of Democratic supremacy in Sacramento, moderate Democrats have been a vital bulwark for oil and petroleum producers to check more progressive lawmakers’ most aggressively green impulses — for example, a proposed ban on gas-powered cars.

Together, the industry’s two political action committees have focused their spending on five races. And like their peers in other industries, they are supporting moderate Democrats in four of them: Rubio in Whittier, Nora Campos, who is running to replace a termed-out Sen. Jim Beall in San Jose, and two Stockton-area Democrats: Mani Grewal who is running for Senate and Carlos Villapudua who is running for Assembly.

Spending may not always be what is seems

When a candidate’s campaign spends its own money in a race, the goal is generally self-evident: to get its contender elected.

Independent spending can be harder to parse.

This week, a committee sponsored by the industry group representing the state’s landlords dropped nearly $45,000 in support of Jim Ridenour, a little-known Republican candidate for Senate in Modesto who has done next to no public campaigning and has raised only $7,900 on his own. That only adds to ongoing speculation that support for Ridenour may be a way to split up the Republican vote, ensuring that the moderate Democrat in the race, Mani Grewal, will make it into the general election.

Likewise, the state Association of Realtors’ decision to spend more than $30,000 to help Simi Valley Democrat Steve Fox, who is hoping to beat vulnerable Republican Assemblyman Tom Lackey. But Fox is saddled with a history of sexual harassment allegations. That prompted an outraged response from Democratic consultant Bill Wong on Twitter.