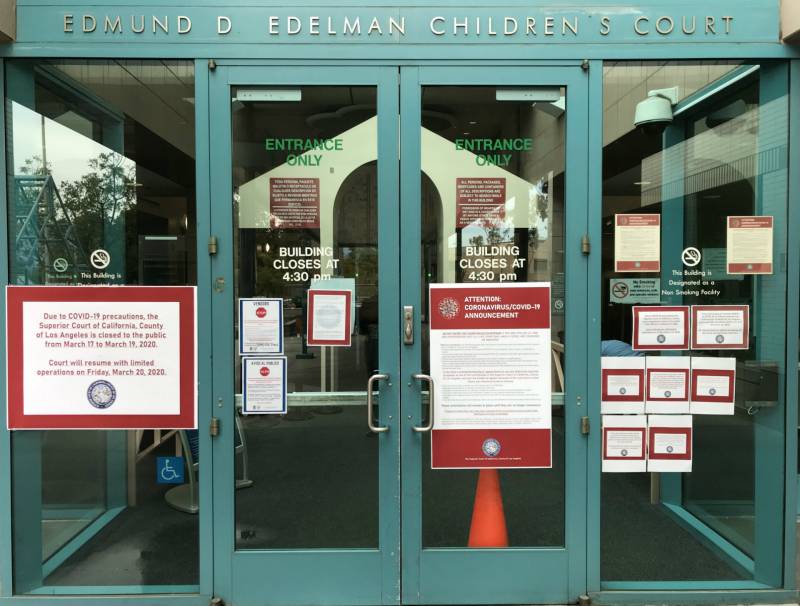

It was a scene of confusion and despair early Tuesday morning in front of one of the nation’s largest children’s courthouses in Los Angeles as parents, some with children and babies in tow, stood helplessly outside the closed building.

“The notice on the courthouse door says that the court is closed for three days and doesn't really provide a lot of information about what to do,” said Leslie Heimov, executive director of the Children's Law Center of California, who was informed of the temporary closure the night before.

Heimov and her staff attorneys provide legal representation to children in the child welfare system in Los Angeles and Sacramento. On Tuesday, Heimov found herself explaining the closure to a confused parent.

“They were all told to come to court, so they're showing up, some of them taking public transportation, some with their babies with them,” she said. “Not surprisingly [it’s] a lot of very distressed folks.”

The Edmund D. Edelman Children's Courthouse in Los Angeles County's Monterey Park hears cases that relate to allegations of abuse or neglect of a child. Parents with a scheduled hearing check in at 8:30 a.m. Many show up early to wait throughout the day for their cases to be called. Some are there to regain custody of their children, and others are there to show their progress on a court-mandated plan before reunification can occur. Some parents might also learn at that courthouse that their parental rights have been terminated.