For some, the coronavirus pandemic brings back memories of the struggle against AIDS and serves as a reminder of San Francisco in the early 1980s. This is especially true for those who helped lead that fight 40 years ago.

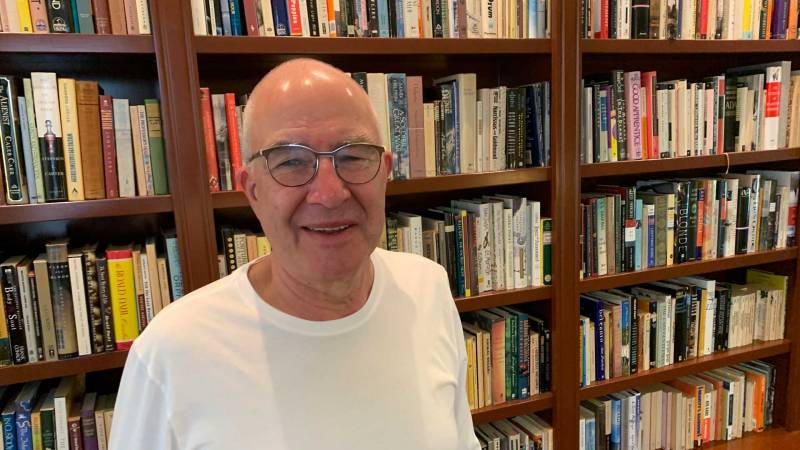

"1981 was an amazing year," Dr. Paul Volberding recounted recently. He had just finished his training as an oncologist — a cancer specialist, and on rounds the very first day he recalls seeing "the first patient with Kaposi’s sarcoma that was admitted to the hospital."

It all started as part of a curiosity for Volberding. "To me, it was a very interesting cancer. Wow!" he recalls thinking about the 22 year old who was his first patient. "I looked in the books and it wasn't supposed to be in 22 year olds at all," Volberding said.

Volberding was suddenly on the frontlines of a mysterious illness during a crisis where medicine, public health and politics collided head on.

The contrast of the confusion regarding AIDS then, to what we know today is stark. "Today, we know exactly what COVID-19 is, right down to its gene sequencing. The virus is already being studied for possible clues to effective treatments," Volberding said.

With AIDS, it was years before scientists discovered exactly what caused it. Until that was known, there was fear — bordering on hysteria at first — that the disease could easily be passed along through sneezing or touching, eerily reminiscent of the novel coronavirus today.

Roma Guy remembers AIDS as "this mystery disease," where people were "falling like flies," and no one knew why. Guy was an organizer in the women’s community in San Francisco at the time. As the AIDS toll mounted, she described the prejudice against those diagnosed with the illness, especially gay men and people of color.

Guy, who went on to serve as a city health commissioner, says AIDS was like a medical earthquake that forced a new way of thinking. "The public health system had to go through a whole transformation," she said, because it wasn't set up to deal with this kind of epidemic at the time.

In 1982, Diane Jones, now Guy's wife, had just graduated from City College of San Francisco School of Nursing and went to work at San Francisco General Hospital. She ended up working on 5B, the world's first inpatient HIV unit, for 15 years. Fear was one of her most vivid memories from that time.

"I could come in at eleven o'clock at night and there would be patients with three meal trays stacked up outside the room because people were too afraid to go in and nobody was really giving any guidance," Jones recalled. "This issue of really not knowing for certain how it's transmitted is really different than the situation that we have right now with the coronavirus."

Largely forgotten, said Jones, were women — many of them lesbians who were helping gay men have children by using the "turkey baster" method, as she called it. Those artificial inseminations left them worried about becoming infected with the virus.