For two weeks in March, Dr. Raynald Samoa fought to move air through his lungs. After recovering from COVID-19, the Los Angeles-based diabetes specialist posted videos on Facebook urging others to stay home. His posts resonated with California’s small but tight-knit Pacific Islander community as questions and stories flooded his inbox.

One family described the anguish and guilt of watching a loved one struggle out of bed to the ambulance — “the least Pacific thing that you can do,” Samoa said — because the first responders wouldn’t come inside. Another family revealed how three breadwinners were hospitalized with the disease, unable to care for their kids.

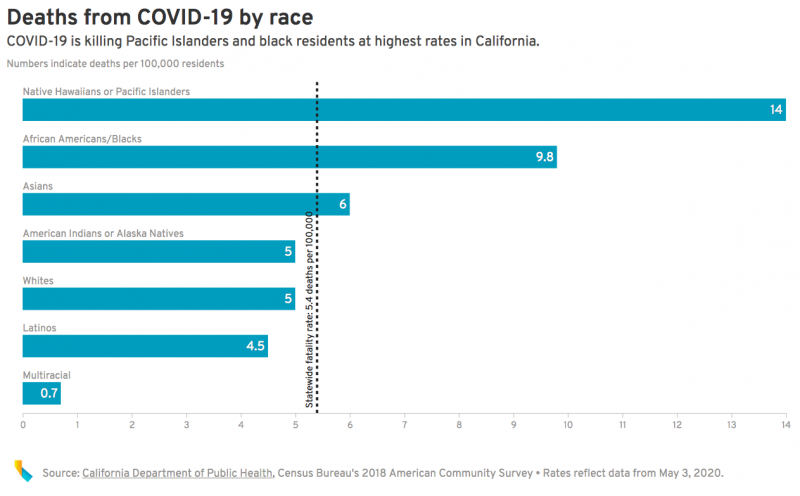

Across the country, the novel coronavirus has laid bare the life-and-death consequences of racial inequality, which has disproportionately killed more African Americans. Now, a stunningly similar pattern has emerged among Pacific Islanders in California, exposing a public health blind spot that will likely require re-evaluating coronavirus tracking for this small, communal population.

Already, the rate of infection among Pacific Islanders has alarmed public health experts and community leaders. As of Sunday, the novel coronavirus had infected Pacific Islanders at a rate more than twice that of the state as a whole — and killed them at a rate 2.6 times higher, the highest rates of any racial or ethnic group.

While the numbers are still small — California reported 416 known cases and 20 deaths among Pacific Islanders — they reveal a growing threat in a community that suffers disproportionately high rates of chronic illness, accustomed to living in multigenerational households and work higher-risk jobs such as food service, transportation and health care that can’t be done from home.

While Health Officials Debate, Advocates Sound Alarm

In an email statement, the state Department of Public Health acknowledged it warrants attention but declined to elaborate how.

In Los Angeles County, where the infection rate is four times that of the general population and the death rate for Pacific Islanders is six times greater, county officials said they are reassessing outreach efforts.

Other counties, however, warned against jumping to conclusions.

“Even small changes in numbers can mean large changes in rates — and with just one death in this group, there is very little we can conclude,” said Sarah Sweeney of San Diego County’s health agency.

In recent weeks, Pacific Islander community leaders and health advocates have sprung into action, holding countless video conferences, requesting more granular data from county officials and leveraging the central role of faith in Pacific Islander cultures.

To Tana Lepule, that one San Diego death represented the loss of a family member. The longtime health advocate said that small numbers have always masked very real health issues among Pacific Islanders.

“The sadness and grief is just the same,” he said.

Common Misconceptions

Approximately 317,000 people with origins from Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, Fiji, the Marshall Islands or other Pacific islands live in California — less than 1% of the state’s population.

Though the official census category is Native Hawaiiwan or Pacific Islander, advocates use Pacific Islander to encompass the group. Most Pacific Islanders live in Los Angeles, San Diego, Sacramento, Alameda and Orange counties. However, there’s a cluster of 90,000 people with Pacific Islander heritage in the Bay Area’s nine-county area.

Common misconceptions that Pacific Islanders are Asian can muddy the data, said Ninez Ponce, director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. So can variations in how hospitals classify Pacific Islanders, half of whom identify with another race.

But after controlling for a shortage of tests and other variables, Ponce and two other UCLA researchers concluded that the rate of infection in Pacific Islanders “is at least twice that of the state rate, and likely to be nearly three times as high.”

The heavy burden didn’t surprise Brittany Morey, a public health professor at UC Irvine researching social and health inequities in Pacific Islanders.

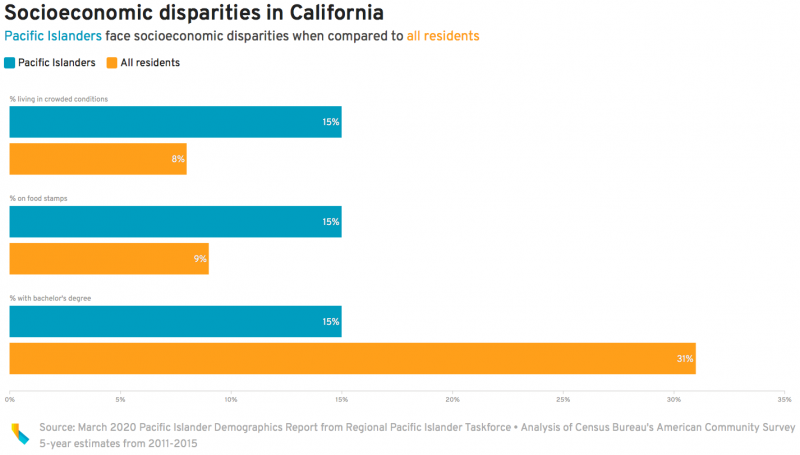

Pacific Islanders are likely more vulnerable to the coronavirus since they are more likely to face poverty, live in dense neighborhoods and crowded homes, and work low-wage essential jobs that increase their risk of exposure.

And while public health researchers lump Pacific Islander data with Asians, they probably share more social-economic traits and chronic conditions with African Americans, Morey said.

In California, about 23% of Pacific Islanders have experienced asthma, compared to about 16% of all residents, 2017 and 2018 California Health Interview Survey data shows. About 37% are obese compared to 27% of the overall population. Pacific Islanders are nearly twice as likely to smoke as the general population. Across the U.S., Pacific Islanders are 2.5 times as likely to have diabetes as non-Hispanic whites.