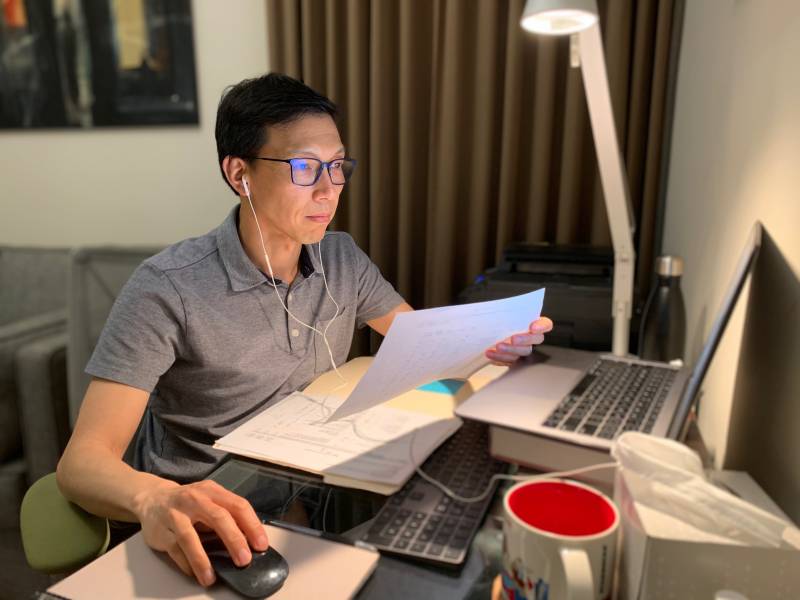

At the same time Eric Chan started training to become a contact tracer, he also started tuning in to Chinese-language news on TV.

He wanted to brush up on his Cantonese, especially the medical terms for the pandemic, so it would be easier to talk to people who weren’t comfortable with English, especially those who might assume his call is a scam.

“Quite often, just speaking that language directly, instead of having the interpreter on the line, it helps a lot with the communication and the trust,” he says.

Normally, Chan works as a financial analyst in the San Francisco Assessor’s Office. Now, he is one of 73 city employees, including librarians and paralegals, who have been trained as contact tracers to notify people when they’ve been exposed to the coronavirus and ask them to stay home for two weeks to prevent further spread. The city has focused on recruiting people who speak multiple languages in an effort to reach communities of color that have been hardest hit by the virus.

Nearly half the people who have died from COVID-19 in San Francisco are Asian American. Statewide, Latinos account for 54% of coronavirus infections even though they make up 39% of the population.