There is something potent that when Lewis died on July 17, it was in the middle of another civil rights movement. The fact that his lifelong calls for justice, for an end to police violence, and for voting rights are still necessary shows how America’s founding promise of freedom is also our unfinished business.

But Lewis never stopped believing in the power of people to one day finish the job. He even left behind a comic book — the three-part graphic novel memoir March — to share his story with the next generation.

To promote the book, Lewis went full fanboy, showing up at San Diego’s Comic-Con multiple times. Lewis even cosplayed himself — recreating his famous march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in the halls of San Diego’s convention center. He replicated his outfit, scouring thrift stores to find a trench coat that matched the one he had worn 50 years before and filling a vintage backpack with fruit, water and books. This time it wasn’t 600 protesters, but a group of school children who took his hands and followed his lead.

So how did a sitting U.S. congressman and iconic civil rights leader end up becoming a best-selling graphic novelist and Comic-Con’s favorite cosplayer? As you might expect, there’s an origin story.

A group of staffers on Lewis’ 2008 reelection campaign were sitting around, talking about summer plans, including Andrew Aydin.

“Unashamed, I said I would be going to a comic book convention. And there was a little teasing, but Congressman Lewis stood up for me,” Aydin recalled.

Lewis said, “I just said, ‘You shouldn’t laugh. At another time in another period there was a comic book called The Montgomery Story ― Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery story — that inspired me.”

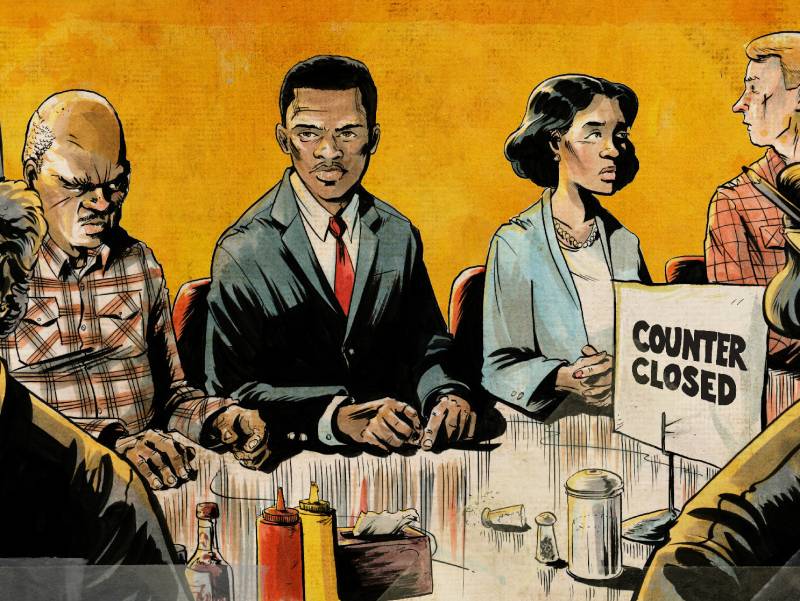

In 1958, at 18 years old, having just arrived at college, Lewis stumbled upon a comic book that played a role in his rapid evolution into a civil rights leader. The 16-page long comic tells the story of Rosa Parks’ symbolic refusal, and it also gives a detailed account of how to practice nonviolent resistance. It was a lesson Lewis took to heart when he staged sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville in the late ’50s.

“It was on February the 13th, and we had the very first sit-in here,” Lewis said in a 1960 NBC documentary. “I took my seat at the counter. I asked the waiter for a hamburger and a Coke.”

Lewis’ staffer, Aydin, knew the history but he hadn’t known about the old comic book. Aydin became convinced Lewis should tell his story as a graphic novel. But Lewis wasn’t so sure.

“I thought he was somewhat out of his mind. Why would I be writing a comic book?” Lewis said.

But then he thought back: “I do remember reading The Montgomery Story comic book, and I said, ‘Yes, if you would do it with me.’ And it’s been a labor of love.”

That labor brought Lewis, alongside co-writer Aydin and the book’s artist, Nate Powell, to Comic-Con in San Diego to launch the first book in 2013. While the geek and supernatural mecca known for its outlandish costumes may seem like an odd location for a sitting congressman, almost immediately Lewis fit right in.

Waiting in line for Lewis’ signature, right next to a guy in an elaborate transformers costume, was Mary Clark, a teacher at San Elijo Middle School in San Marcos.

“This will go into my library collection,” Clark said. “As a graphic novel, sometimes students who aren’t really enthusiastic readers will pick it up thinking it’s about the pictures.”

In other words, graphic novels like this can be the history equivalent of hiding healthy Brussels sprouts in a fussy eater’s mac and cheese.

Lewis was always adamant that March was more than just biography. Like the Martin Luther King Jr. comic book that inspired him, the trilogy was always meant to be a primer on protest and what it means to march for justice.

In 2016, the third book in the March trilogy won a National Book Award. Lewis, with Aydin and Powell beside him, gave a powerful speech. Through tears, he recalled that when he was 16 years old, he tried to get a card from his local library. There were few books at home, and he wanted to read.

“We were told the library was for whites only, and not for coloreds,” Lewis said. It is a meaningful reminder of the distance we have traveled since then.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day earlier that same year, a group of Black Lives Matter protesters gathered on the Bay Bridge between Oakland and San Francisco. For hours they blocked five lanes of traffic on the westbound span. They were dressed to the nines in their Sunday best, donning suits and fedoras.

They dressed like that, they said, to replicate and echo the marchers on another bridge, on another day, in another chapter of this fight. Their outfits were a direct nod to Lewis’ march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

It is a meaningful reminder that we are still a bridge too far from the justice Lewis fought for, which is perhaps why he left an instruction book, in the form of a graphic novel.