When the call came in over the radio, Jinho Ferreira was on patrol in the outskirts of San Leandro, getting ready to end his shift.

“It was a call for shots fired,” he said. “I showed up, and there was a man dead in a parking lot.”

The man was Black, and he had been shot to death by several Alameda County sheriff’s deputies.

Ferreira felt apprehensive. A successful rapper who’d had run-ins with the police himself, Ferreira had joined law enforcement for one reason: to fight a white supremacist system from the inside.

“I was thinking about occupying a badge and a gun, and using it in accordance with my values,” he said. “I needed to know if that was impossible.”

As he started taking statements from bystanders, Ferreira said he thought, “I was blocks away from this when it happened. … What is this going to turn into?”

Lesser of Two Evils

Before he became a cop, Ferreira didn’t trust them very much.

He grew up in the 1980s and 1990s in West Oakland, the home of the Black Panthers. Ferreira’s mom was a former Nation of Islam teacher who worked for Pacific Gas & Electric, and she raised her son on a steady diet of Black revolutionary theory.

It was also the height of the crack epidemic, a public health crisis that fueled crime. Some people turned to the police, but as Ferreira put it, “you’re kind of choosing a lesser of two evils.”

In the late 1990s, a group of Oakland Police Department officers known as the Riders allegedly kidnapped, beat and falsely arrested countless West Oakland residents. The city eventually settled the case and agreed to pay nearly $11 million to 119 different plaintiffs.

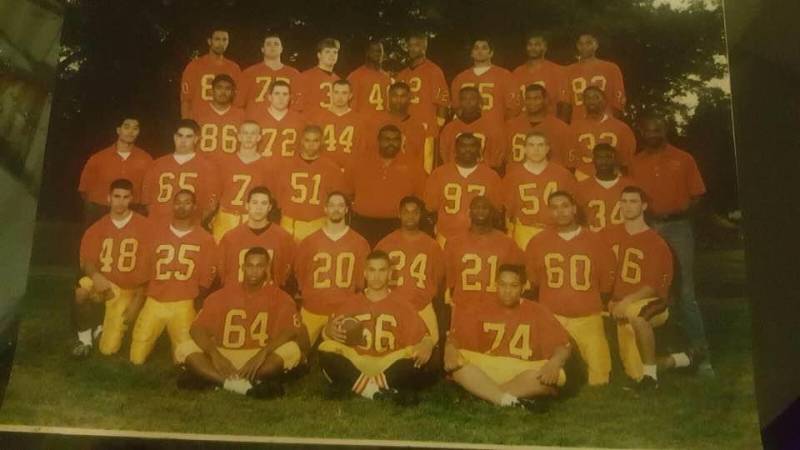

When he got to high school, Ferreira tried to keep his head down. He focused on football. That’s where he met Jihad Akbar.

“He was pretty much getting straight A’s all through high school,” said Ferreira. “He was the most politically aware of any of us, and he was a leader.”

Akbar attended UC Berkeley and grew into a dedicated activist, devoting his time to AIDS prevention and juvenile justice. But as the years went by, Ferreira said his friend began struggling with mental health issues and started to self-medicate. Akbar tried to get help but had trouble getting into a residential treatment program. Sometimes he’d get high and get paranoid about law enforcement, and Ferreira would spend hours just sitting with him.

Then, in October 2002, Ferreira got a call from a friend.

“He told me that Jihad was dead and the police killed him,” Ferreira said.

‘It’s My Job to Tell the World About Him’

Ferreira found out the details later. Akbar allegedly ran into San Francisco’s Baghdad Cafe and stole several knives, then started dancing with them in the street outside.

“He was obviously having some type of mental breakdown,” Ferreira said. “Two cops showed up. He supposedly lunged at one of them, and they shot him, and he died.”

Akbar’s death made the news. Ferreira remembered one article describing his friend as a violent homeless man. He said it didn’t mention that Akbar had gone to UC Berkeley or been a straight-A student.

“I can’t leave it up to the guy that wrote that article about Jihad to tell the world about him,” he remembered thinking. “It’s literally my job to tell the world about him.”

At this point, Ferreira had been rapping for several years. In 2003, he got together with a singer and a guitarist at an Oakland recording studio and started a group called Flipsyde.

“If you go back through all our songs, 90-95% of them deal with how this system victimizes people,” he said. “I’m carrying everything with me — all the people that have passed away with me — and I’m working as hard as I possibly can.”

The group took off. Flipsyde traveled the world with Snoop Dogg, Akon and the Black Eyed Peas. In 2006, NBC made their song “Someday” the theme song for their Winter Olympics coverage. But they were always a bigger deal abroad than they were back home.

“I needed to do more than just write a song,” Ferreira said.

For Ferreira, the turning point came on New Year’s Day in 2009. In the early hours of the morning, Oscar Grant was shot by a white police officer on the platform of Oakland’s Fruitvale BART Station. His death was filmed by bystanders. Ferreira watched the video and took to the streets.

“I go to the protest,” he said. “And I remember a journalist was interviewing artists. And he said, ‘What can we do as artists to make sure this never happens again?’ ”