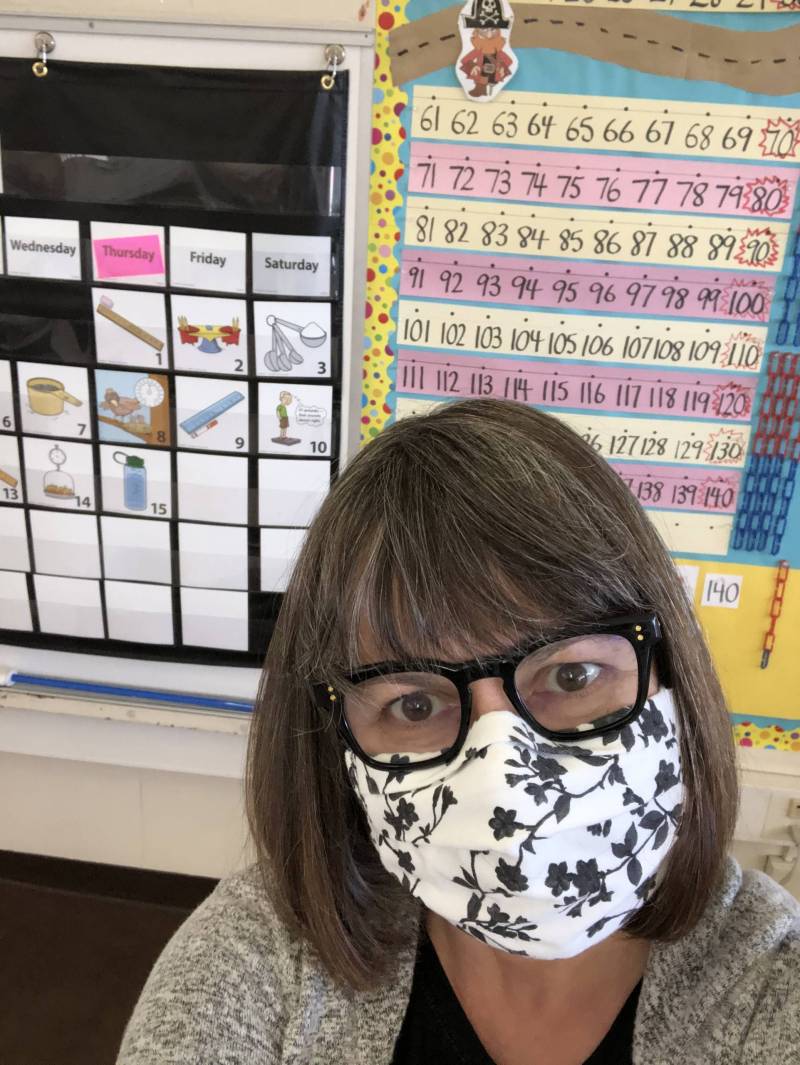

Two weeks after she returned to her classroom in person, first and second grade teacher Andreanna Yanez-Vierra found herself working 10- to 11-hour days. Come quitting time, she said, teachers are “just physically and emotionally exhausted.”

Outside Hoover Elementary School in Burlingame, where students started their return to campuses in February, Yanez-Vierra begins her days at 8:30 a.m., more nurse than educator as she greets kids before taking their temperature.

After she gets her eight first graders sanitized and settled into their spaced out desks, Yanez-Vierra logs into Zoom to connect with the three students who remain in distance learning. She takes attendance, and in the afternoon does it all over again with her second graders.

While San Francisco and Oakland teachers who have just arrived back in their classrooms are now facing the hybrid learning reality many of them dreaded, around the Bay Area, teachers like Yanez-Vierra have already been juggling in-person and online students for months.

Trying to keep her distance learners on track while managing the students in her classroom is testing all the experience she has gained from 31 years of teaching. For example, she has to turn her laptop toward the students in the classroom so the two groups can see each other while they complete assignments. “Internet issues are always coming up,” she said. “Of course.”

Then there’s the way all the months of online school seem to have changed the kids.

“They’re just blank stares,” she said.

Online school came in bite-size chunks — live lessons were short, and kids could start and stop her recorded lessons whenever they felt like it. Distractions were constant. Now she says kids don’t have the stamina for two-plus hours of class.

“I have to put my tap shoes on and dance around a little bit before I can really wake them up,” Yanez-Vierra said.

Spending only a couple of hours a day with the kids in person, she has to spend much of that time teaching them basic classroom organizational skills they should have learned at the beginning of the year.

“All of those management pieces that happen in a classroom really didn’t happen at home,” she said. “It’s real evident when the kids come back to school, because papers are falling all over and they can’t find things.”

At least her students are remarkably good at keeping their masks on and staying away from one another.

Maintaining her distance from them is a different story.

“You get in the classroom and it’s kind of like, ‘I have to do this, I have to show them where this page is. Even though we were afraid of all that, now that the kids are with us, it’s kind of gone out the window,” she said. “We do what our heart tells us to do and you can’t stop that. It’s hard.”

Palo Alto kindergarten teacher Corey Potter, who has been back in her classroom since October, still struggles with social distancing. Masks make it impossible to hear students 6 feet away, she says.

“We’re put in a position every day of having to decide: ‘Do I move closer and put us both at risk just so I can hear what they’re saying?’ she said.

Potter is also juggling in-person and distance learners. Her classroom students come to school in the morning for a couple of hours, with distance learners joining for a 45-minute concurrent session. She meets with distance learners separately again in the afternoon.

Even after months of this balancing act, she estimates spending an extra eight hours each week on lesson planning. It’s not just developing lessons that work online and in-person, she says. So much of how she previously taught relied on partner or group activities, and she can’t do any of that now.

“There’s a whole lot to keep organized,” she said. “To keep both groups in the same place in the curriculum is challenging.”

In Napa, third-grade teacher Courtney Garcia works with her distance learners in the morning and in-person students in the afternoon. She sees an upside to the hybrid model.

“Should a child that’s in person need to quarantine, they can easily switch over and be part of my virtual group,” Garcia said. “So none of my students are losing any sort of educational time.”

What’s a problem is not being able to hug the kids. “Especially when you’re so excited for them, when they’ve accomplished something and they come bopping over to you and you can’t hug them,” Garcia said. “That’s the worst part.”

Today, Yanez-Vierra has been back in the classroom for more than two months. In that time, she says, a staff member contracted COVID. She says teachers had to go back to working from home temporarily. (The district won’t confirm this, but its COVID dashboard shows one positive case in March.)

“The teachers were all at home and they had to Zoom in and the students were back in class,” Yanez-Vierra said. “It was really crazy.”

Otherwise most things are getting easier. She’s working fewer hours, and she says the kids are learning to stay organized at school.

“They can find something and get it ready so much quicker than those that are still at home — you know, they don’t have a desk, they don’t have a bin. Or maybe their parents haven’t printed out the PDF,” Yanez-Vierra said.

The kids who are now physically attending class are building their focus, too.

“They’ve started to develop that stamina again — paying attention, listening to somebody, looking with your eyes to see how someone feels — all of those important things were falling to the wayside,” Yanez-Vierra said.

While she’s finding her rhythm, she’s still not a fan of hybrid learning.

“We’re hoping that maybe the district figures out [hiring] a distance learning teacher or teachers to do that,” she said, “because it’s just nuts.”

At this point, Yanez-Vierra wants schools to reopen full time as soon as possible.

And she’s trying to convince the parents of her distance learners to send their kids in.