The Biden administration is expanding its effort to find and reunite migrant families who were separated at the U.S.-Mexico border during the Trump presidency.

Biden Administration Launches Website to Help Reunite Families Separated at the Border

A federal task force is launching a new program Monday that officials say will expand efforts to find parents, many of whom are in remote Central American communities, and help them return to the United States, where they will get at least three years of legal residency and other assistance.

“We recognize that we can’t make these families completely whole again,” said Michelle Brané, executive director of the administration’s Family Reunification Task Force. “But we want to do everything we can to put them on a path towards a better life.”

As part of the new program, the federal government has agreed on a contract with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), an intergovernmental body that helps manage migration patterns and provide humanitarian assistance.

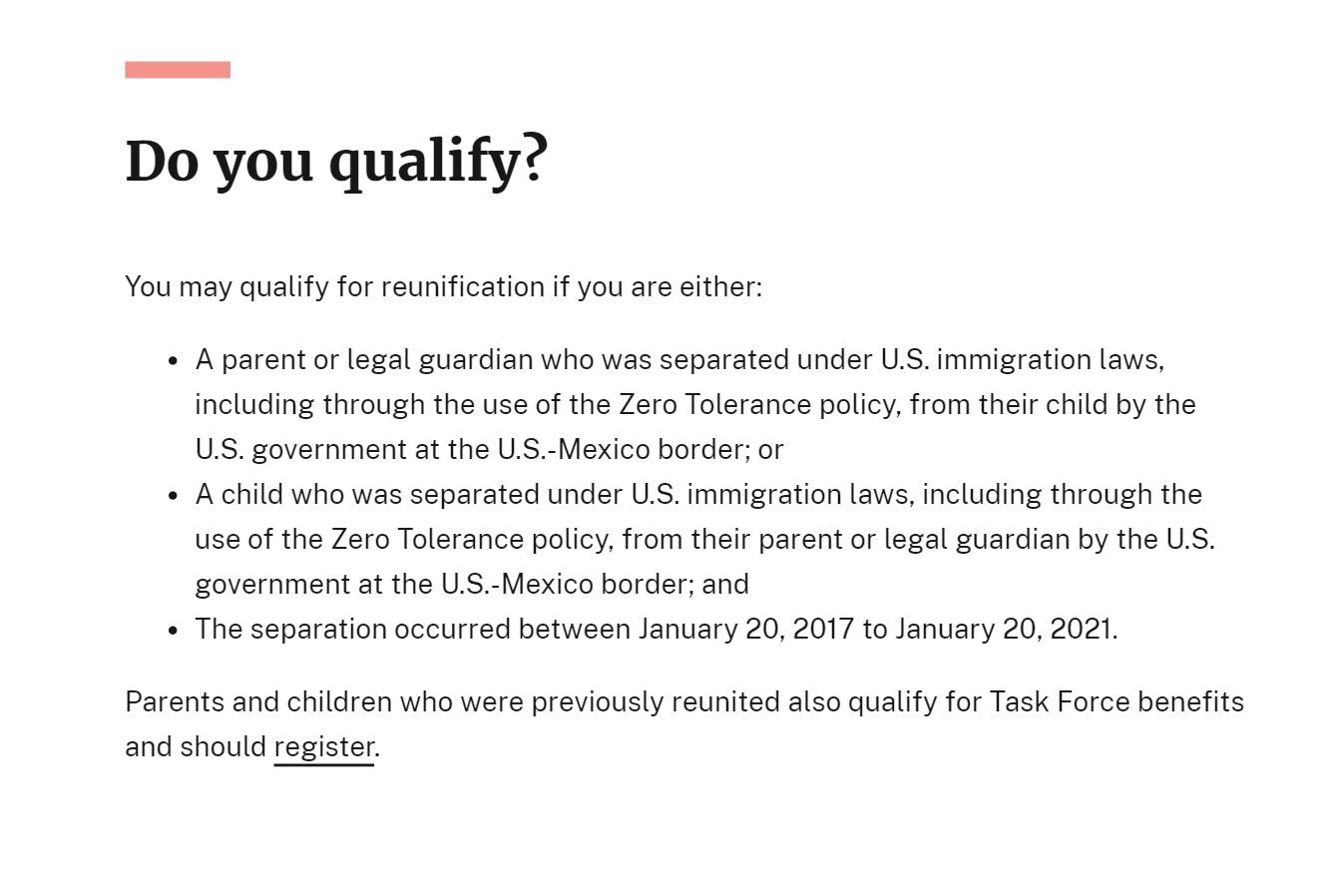

The program also includes a web portal, together.gov, that will allow parents to contact the U.S. government to begin the process of reunification. The site and an outreach campaign to promote it will be in English, Spanish, Portuguese and several Indigenous languages of Central America.

The IOM will help with the logistics of reuniting families, explained Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, who welcomed the Biden administration’s expanded efforts as “an important first step,” though he believes migrants should get more than three years of residency.

The IOM will also be tasked with “allowing the family to get passports more easily, [getting them] to the U.S. embassy, [getting] travel documents, [making] plane reservations, but also simply to get them from one place to another,” said Gelernt.

Most of the parents are believed to be in Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Brazil. They often lack passports and the means to travel to the U.S. to try to gain entry at the border.

“Sometimes they are living in rural communities, hours and hours away from the capital city, sometimes they need protection when they make that trip,” Gelernt explained.

Once parents are located and return to the United States, they will receive work permits, residency for three years and some support services.

“Ultimately, we need the families to be given permanent legal status in light of what the United States government deliberately did to these families,” Gelernt said.

The ACLU is in talks with the government to provide some compensation to the families as part of settlement talks.

A new strategy for an ongoing problem

Bringing the IOM on board to help with the often-complex task of getting expelled migrants back to the U.S., is a reflection of just how difficult it has been for President Joe Biden’s administration to address a chapter in U.S. immigration history that drew widespread condemnation.

The task force has reunited about 50 families since starting its work in late February, but there are hundreds of parents, and perhaps between 1,000 and 2,000, who were separated from their children and have not been located. A lack of accurate records from the Trump administration makes it difficult to say for certain, said Brané from the Family Reunification Task Force.

“It is a huge challenge that we are absolutely committed to following through to meet and to do whatever we can to reunify these families,” she said as she outlined the new program in an interview with The Associated Press.

The Trump administration separated thousands of migrant parents from their children in 2017 and 2018 as it moved to criminally prosecute people for crossing the southwest border, including those seeking asylum. Minors, who could not be held in criminal custody with their parents, were transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services. HHS faced allegations that, in some shelters, caregivers were instructed not to touch or comfort the children, and in others, children suffered sexual abuse, including by staff members. From the shelters, the children were then typically sent to live with a sponsor, often a relative or someone else with a connection to the family.

Amid public outrage, Trump issued an executive order halting the practice of family separations in June 2018, days before a federal judge did the same and demanded that separated families be reunited in response to a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union.

More than 5,500 children were separated from their families, according to the ACLU. The task force came up with an initial estimate closer to 4,000 but has been examining hundreds of other cases.

‘An apology is not enough’

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas held a virtual call with reunited families last month.

“He made it very clear that an apology is not enough, that we really need to do a lot more for them and we recognize that,” Brané said, and added that the administration recognizes that it needs “to find a better, longer-term solution to provide families with stability.”

But that, Brané said, will take more time, and perhaps action from Congress, to achieve that goal.

The contract with the IOM and the expanded efforts to find migrant parents and help them reach the U.S. are initially planned to run for a year but could be extended if necessary.

“We’ll continue looking for people until we feel that we’ve exhausted the options,” she said.

This effort comes amid an increase over the past year in the number of migrants attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border, especially children traveling alone, in part due to violence and poverty in Central America.

As part of what the Biden administration has portrayed as an effort to address the “root causes” of border crossings, it announced separately Monday that the government would start taking applications for an expanded program that enables children in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to join parents and legal guardians who are citizens or have legal residency in the U.S. That program was halted under Trump.

This post includes reporting from KQED’s Michelle Wiley.