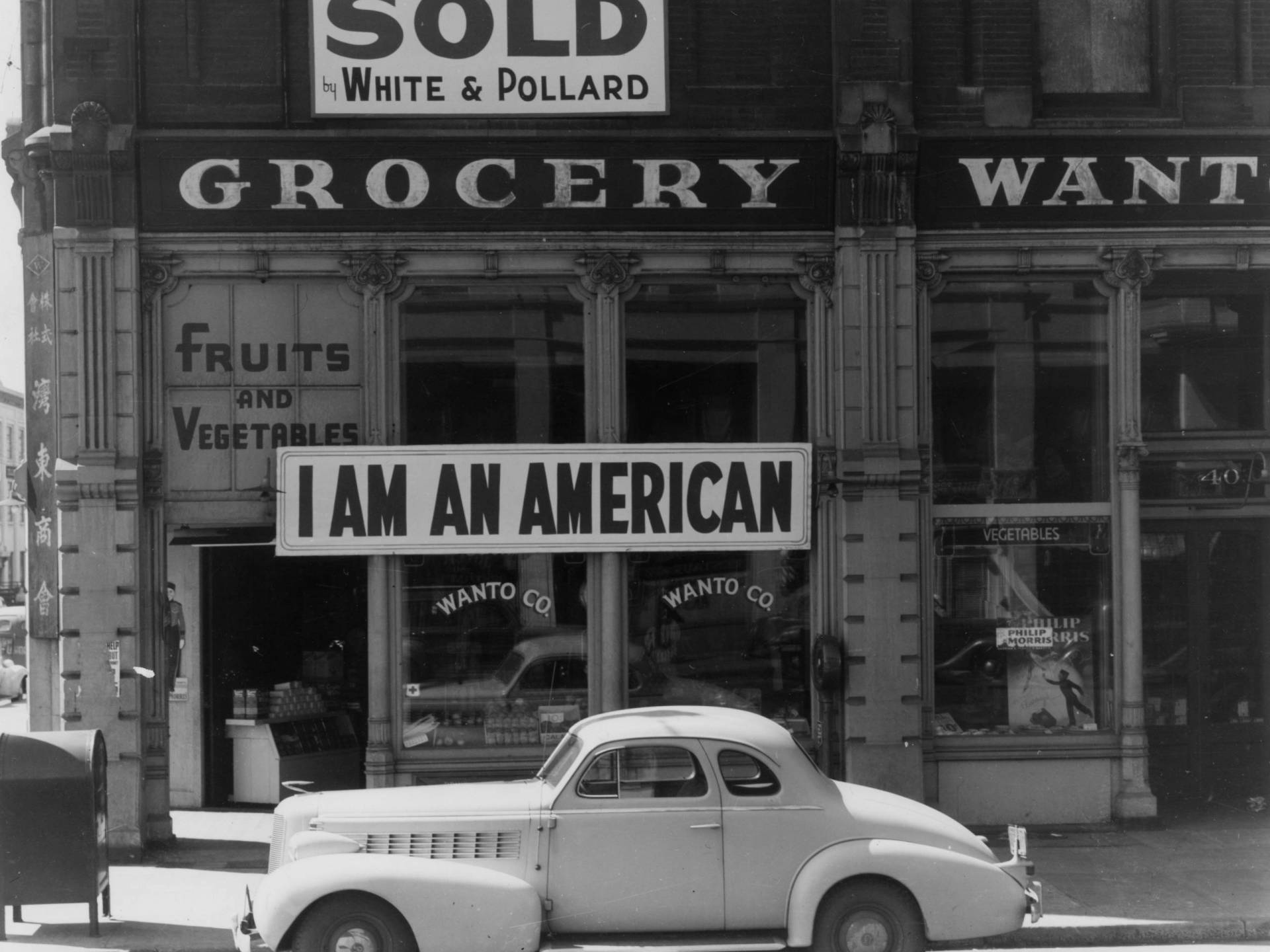

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It sent approximately 70,000 U.S. citizens into concentration camps for years, including a very young George Takei.

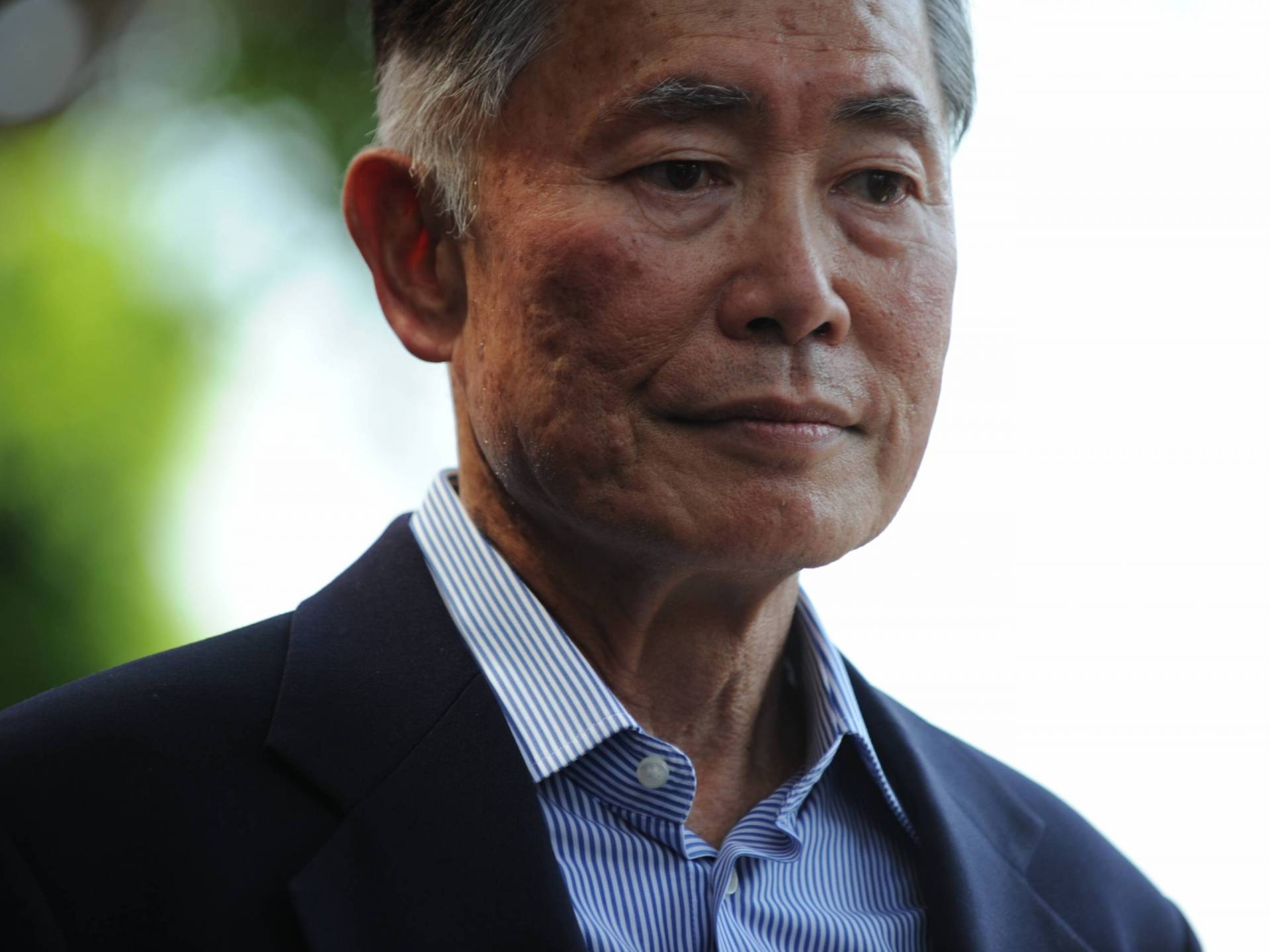

"I was 5 years old at the time," recalls the actor. "It was a terrorizing morning I will never be able to forget. Literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our home."

Best known for playing Mr. Sulu in the original "Star Trek," Takei is a longtime activist whose causes have included LGBTQ rights and reparations for Japanese American survivors of concentration camps. In 1942, his family was sent to Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, then later to Tule Lake Segregation Center in Northern California. The Takei family was among thousands of American families who lost their homes, farms, stores, cars, churches, temples and countless belongings because of xenophobia and racism.

"Some people had their life savings taken from them just because we looked like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor," Takei says.

Collectively, Japanese Americans forced into concentration camps lost more than $6 billion adjusted for inflation, according to an estimate from the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

This is a story George Takei has told over and over: in a memoir, on Broadway, and to members of Congress in 1981. Takei testified at a hearing as part of an effort to push for redress.

"I urge restitution for the incarceration of Japanese Americans because that restitution would, at the same time, be a bold move to strengthen the integrity of America," Takei told a federal commission.

Working with other activists, he succeeded. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, signed legislation to give $20,000 and a formal apology to Japanese Americans who had survived incarceration.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))