Tenants who have applied to California’s emergency COVID rent relief program and are still awaiting a response now can be evicted from their homes, as the last of the state’s pandemic-era eviction protections expired on June 30.

Sulima Navarrete, of Richmond, applied for rent relief in October after her husband lost his job during the pandemic doing construction work.

He also contracted COVID and is still experiencing fatigue and other symptoms, making it hard for him to find new work, she said. The couple has three children, ranging in age from 6 to 20.

“It’s frustrating because it’s not something we asked for,” Navarrete said in Spanish. “It’s something the pandemic brought.”

Exposed to eviction

Navarrete is one of 34,510 applicants for the state’s rental aid program, called Housing Is Key, whose applications were still under review as of June 29.

“It’s highly unlikely that [the state is] going to get through all these applications by June 30th when the eviction protections expire,” said Sarah Treuhaft, a researcher at PolicyLink.

“So, that means that people will still be waiting in line, and they will be exposed to eviction. They’re likely to be evicted or have eviction proceedings against them,” said Treuhaft.

This includes Navarrete, who has already received an eviction notice from her landlord.

“They don’t understand,” Navarrete said of state officials. “The help is coming too late.”

California’s statewide moratorium on evictions expired last fall, on Sept. 30, 2021. The state’s rent relief program has afforded its own kind of eviction protections since then, since any landlord wanting to evict a tenant for failing to pay rent as a result of COVID hardship needed to first apply for rental relief before the March 31, 2022, deadline before continuing with an eviction lawsuit. Renters affected by COVID hardship could prevent an eviction from moving forward if they showed they had applied for the rent relief program as a defense in court. These protections expired on June 30.

Certain jurisdictions — like Alameda County, San Francisco and Marin County — have their own local protections in place that may still shield some tenants from eviction. Read more about resources for people at risk of eviction.

Joshua Howard, of the California Apartment Association, says his group is advising its members to hold off on evicting tenants who are still awaiting aid.

“It’s better to wait and get the money than to go through with the time, cost and stress of an eviction,” Howard said, “especially knowing those funds from the government are just around the corner.”

Attorney General Rob Bonta also issued legal guidance on July 13 to police and sheriff’s departments across the state on how to respond to reports of illegal eviction. That may include landlords changing the locks, shutting off water or electricity, and removing tenants’ belongings in order to force a tenant out of their home, among other behaviors.

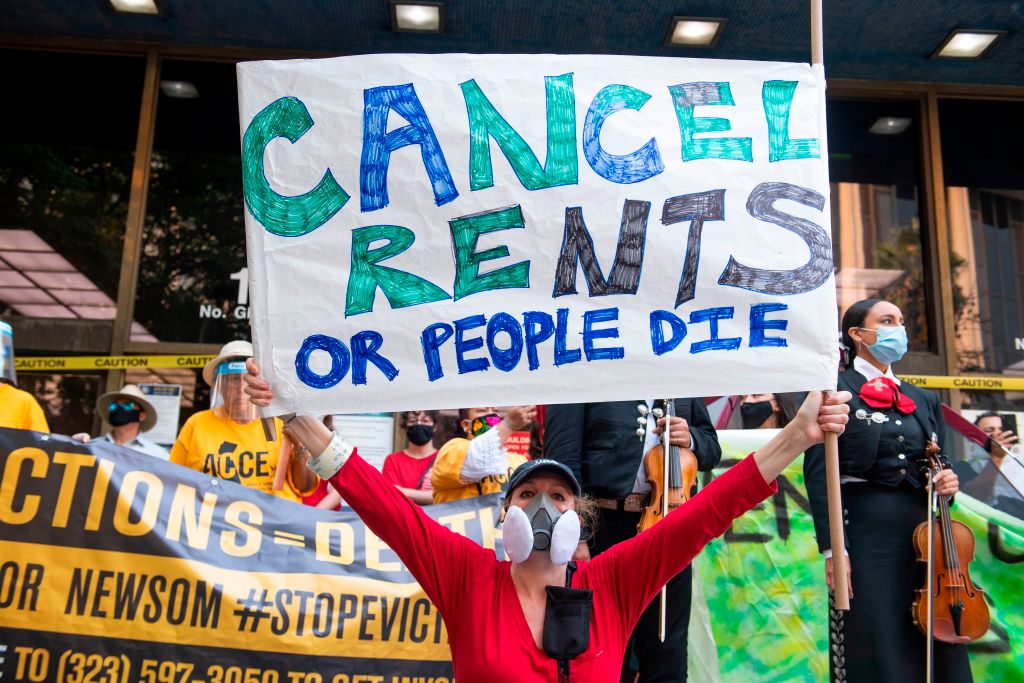

“California’s families are facing a housing affordability crisis at levels never seen before,” he said. “We are facing an eviction crisis.”

Applicants left in limbo

The state processed 136,386 applications, or about 11,365 a week, since it stopped accepting new applications on April 1, said Alicia Murillo, a spokesperson for the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD).

“We have met our goals for processing applications and continue to work diligently to ensure we provide assistance to the qualified applicants,” Murillo said at the end of June. “We are on track to have all initial applications determined by June 30.”

She added, “That is to say, the only remaining applications in the system are those in an appeal process or those where there is still missing or unverifiable information from an applicant.”

But some tenants say they have been frustrated when their attempts to add or verify information are not accepted.

Yadira Placante, a Los Angeles renter, said she received two notices that her application was declined because she was unresponsive, despite two phone calls and an email attempting to respond to the requests.

“I called them and asked them what happened, and they told me I needed to appeal,” Placante said.

Instead, she put in a new application. That was about three months ago, and Placante says she is still waiting for a response.

“It’s been very, very, very like a nightmare for us,” Placante said.

A rise in denied applications

In May, a coalition of tenant organizations filed a lawsuit against the state, claiming its process for denying applications is unfair and opaque. Since the program closed to new applicants on April 1, denials increased from around 20% to about 33% of all applications, Treuhaft said.

“We’ve seen this spike in denials,” she said. “So, that raises big questions around, are people receiving due process or should they actually be denied this assistance?”

On July 7, a judge agreed and ordered HCD to stop issuing denials. Applicants have 30 days to file an appeal, so the judge also ordered the state to keep those cases open until it could determine whether the agency’s process for issuing denials violates applicants’ right to due process.

HCD’s Murillo said all denials receive explanations for why they were denied. The main reason, she said, is that the applicant didn’t qualify for assistance.

That could be for a number of factors, including that the applicant’s income was too high, or they couldn’t demonstrate they were a tenant or that they had lost income during the pandemic. Murillo said that as of June 3, about 89,000 applications, or 62% of denials, were for these reasons.

The remaining 38%, or around 55,200 applications, were denied due to non-responsiveness, she said.

“If an applicant believes we made an error or has more information to share, they can file an appeal through the online portal or by calling the hotline [at (833) 430-2122],” Murillo said. “We also have an appointment center available to help applicants through the appeal in English and other languages.”

‘Families just like mine’

But despite the state’s efforts to keep residents housed during the pandemic, some have been evicted anyway.

Delilah Medina of South Los Angeles lost her hotel job during the pandemic. She started working at Walmart, even though it was a big pay cut.

Medina applied for rent relief and got some money but had to reapply in January for more.

Shortly after that, she said, her partner received an eviction notice. Since her name was on the rent relief application, the landlord was able to skirt the state protections.

“We are not shiftless people,” Medina said. “We are like the millions of Americans who don’t make a wage that supports the rising cost of rent and living.”

Medina says now, she and her two young children live in her car. They occasionally use a friend’s house to shower and rest during the day.

“How many more families just like mine are going to suffer?” she asks.